The thing about experiments is that they don’t always work, but that doesn’t mean they should never be attempted.

Much like Someone to Watch Over Me, 11:59 represents a new departure for Star Trek: Voyager. It is an episode unlike any other episode in the run of series, unfolding primarily on early twenty-first (or, as one character wryly points out, maybe late twentieth) century Earth. As with Someone to Watch Over Me, there is a sense that 11:59‘s closest spiritual companion is an episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. There are any number of superficial similarities between 11:59 and Far Beyond the Stars, another time-travel-to-close-to-modern-day-Earth-episode-without-the-time-travel.

Countdown.

Sadly, the experiment does not quite work out. Someone to Watch Over Me is one of the most charming episodes in the seven-season run of Voyager, while 11:59 is more than a little dull. Far Beyond the Stars is one of the most powerful and evocative episodes of Star Trek ever produced, while 11:59 is a competent piece of television that is almost immediately dated. For all that 11:59 represents a bold departure for Voyager, there is a sense that the episode has very little to actually say. It exists, but it never seems to exist for a particular reason. 11:59 is a frustrating piece of television.

However, none of this matters too much. Voyager has been such a safe and conservative show that any creative risk feels worthwhile, that any departure from the established template feels worth of celebration on those terms alone. 11:59 is an unsuccessful experiment, but it is an experiment nonetheless. For a series as risk-adverse as Voyager, that is remarkable.

“Time’s up.”

Interestingly, and perhaps understandably, 11:59 began development as a very different episode. This original pitch was much more conventional, much more in keeping with Voyager‘s interests and aesthetics. As writer Joe Menosky explained to Cinefantastique:

John had an idea for a Q episode. He had a couple of interesting images, of Q on an ocean somewhere on a beach, either having lost his complete identity as Q, or lost his will to live. Somehow he gets involved with an everyday kind of person, and that person’s fate and life somehow affects Q. That was his pitch, and it had some nice images. For a while Brannon and I were thinking about doing Janeway’s distant ancestor and Q in the year 2000. We also thought about Janeway’s distant ancestor and Guinan, and this might have been a Whoopi [Goldberg] episode. When it finally came down to write it, we did try to go in the direction of no science fiction at all, no guest stars from previous episodes, and just see if we could make it work.

That this episode began as a Q- or Guinan-centric episode makes a great deal of sense. Voyager has largely been defined as a younger sibling of Star Trek: The Next Generation, desperately rooting through its elder relative’s wardrobe for anything that might fit.

Hey, kids! It’s John Carroll Lynch!

Despite being set seventy thousand light years away from the Alpha Quadrant where the Enterprise spent most of its time, Voyager featured quite a few direct crossovers with its predecessor. Both Q and William T. Riker appeared in Death Wish. The Ferengi from False Profits were the same ones who featured in The Price. Reginald Barclay appeared in Projections, and would become a recurring guest star beginning with Pathfinder. Deanna Troi appeared in Pathfinder and Lifeline. Geordi LaForge appeared in Timeless. The Borg were a regular fixture across the seven-season run of Voyager.

As a result, it is no surprise that 11:59 originally developed as another potential crossover between Voyager and The Next Generation, another opportunity to assert a spiritual connection between the two series whether through a return appearance from John deLancie or a guest turn from Whoopi Goldberg. However, what is most interesting about 11:59 is the way that the episode developed from that original pitch. In many respects, the final broadcast version of 11:59 is much more ambitious than the original pitch, which is quite rare for an episode of Voyager.

Taking a time out.

Traditionally, Voyager has a habit of reining in crazy and outlandish ideas during the development cycle. There are any number of episodes that sounded far more ambitious in their original pitch than they did as a finished script. Brannon Braga had originally pitched Macrocosm as a silent episode of Voyager, but the finished episode is weighed down by exposition. Michael Taylor originally pitched Once Upon a Time as a story from the perspective of Naomi Wildman. The original proposal for The Fight was much more interesting and intricate than the finished product.

As such, it seems strange that the core idea for 11:59 survived the development process once the familiar elements like Q or Guinan were removed. It is a credit to producer Brannon Braga, who often longed for more ambitious storytelling only to find himself restrained by the franchise’s more conservative impulses. Dropping Q and Guinan, 11:59 decided to construct a story set on Earth in late December 2000 featuring only one familiar actor playing one unfamiliar character. While this was superficially similar to Far Beyond the Stars, it was still a story unlike any Voyager had ever told.

Lightening the mood.

Of course, 11:59 is still a Voyager episode through and through. 11:59 is unmistakably an episode of Voyager, in more than just the casting of Kate Mulgrew or the awkward framing device filmed on the existing sets using the primary cast. Thematically, 11:59 is engaged with ideas that simmer through Voyager, concepts that play out across the seven seasons of the Star Trek spin-off. 11:59 is an episode that deals explicitly with questions of memories and history, anchored specifically in the context of the late nineties.

Indeed, 11:59 makes a point to emphasise that the December 2000 setting is still technically part of the nineties. Henry Janeway suggests that the characters are trapped in some sort of millennial purgatory where every December 31 teases the possibility of a new beginning that never materialises. “Speaking of the modern age,” Henry asks Shannon, “do you have any plans for the Millennium Eve?” Shannon replies, “No different than last year’s Millennium Eve.” The implication seems to be that the nineties did not end in December 1999 and they may not end December 2000.

We need to talk about Kevin Tighe.

11:59 offers an interesting glimpse of millennium life, one built around the idea that there is absolutely nothing special about the date that had been arbitrarily set as the end of the twentieth century. “When the world didn’t end and the flying saucers didn’t land and the Y2K bug didn’t turn off a single light bulb, you’d think everybody would have realised it was a number on a calendar,” Shannon reflects. “But, oh, no, they had to listen to all those hucksters who told them the real millennium was 2001. So this New Year’s Eve will be as boring as last year.”

There is something quite refreshing in Shannon’s cynicism, especially against the backdrop of the overwhelming millennial hype that dominated so much of the late nineties. There was hype around so-called “millennium babies”, while even champagne salespeople hoped to cash in on the hype. The Egyptian government worried about conspiracy theorists trying to break into the pyramids to expose illuminati rituals. Cults predicted the end of the world as people. Apocalyptic dread seeped into the mainstream. Pop culture embraced the apocalypse in films like Stigmata, End of Days, Armageddon.

An economic crash.

As such, there is something refreshing in how confidently 11:59 asserts that the turn of the millennium would represent no significant change, even if Shannon’s commentary is a little dismissive of the hard work that was done to ensure that the millennium bug caused minimal disruption. Even the setting of 11:59 feels quite pointed. Broadcast in May 1999, the episode is actually set in late December 2000. Baked into the premise of the episode is the assumption that nothing spectacular or earth-shattering occurred on December 31, 1999.

Then again, this arguably represents another strand of cultural anxiety running through the nineties, a twisted mirror image of that apocalyptic dread. As much as people feared that the world might end at the turn of the millennium, there were many people who feared that the world would instead freeze in the late nineties. There was a creeping sense that the transition to the twenty-first century might not mean anything of note, because the world was no longer moving forwards. Even the arrival of the new millennium would not be enough to bring an end to the long nineties.

Game on.

The first forty-odd years of the so-called “American Century” were propelled by a sense of movement and purpose: the race to put the first man in space, to place the first boot on the surface of the moon, to wage an ideological war against a perceived existential threat. There was a sense of forward momentum in the years immediately following the end of the Second World War; the establishment of bases in western Europe, the waging of land wars in Asia, Hawaii becoming a state. There was also radical domestic social changes like the civil rights and feminist movements.

With the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the world did not stop spinning, but it seemed to slow. There were still foreign wars, but they tended to be smaller and more contained; the Gulf War, Haiti, Bosnia. Peter Huchthausen would describe these conflicts as “America’s Splendid Little Wars”, in contrast to the conflicts either side. Whereas earlier decades had suggested that the new American frontiers were external, the development of the internet suggested that the new American frontier was within rather than without.

Keeping on (lap)top of things.

Critics have taken to using the term “the long nineties” to refer to this lacuna existing between 1989 and 2001, the gap between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the World Trade Centre. Charles Krauthammer described the period following the end of the Cold War as “the unipolar moment”, but that moment seemed to last a surprisingly long time. Francis Fukuyama described the end of the Cold War and the triumph of liberal democracy as “the end of history.”

To be fair, the nineties did eventually end. Francis Fukuyama was ultimately proven wrong in his assertion that history had come to an end, but it took a long time for another existential struggle to emerge to replace the Cold War. It has become commonplace to treat the nineties as the twelve years falling between the collapse of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the attack on the World Trade Centre in September 2001, markers used by writers like Alexandra Schwarz and Phillip E. Wegner. Still, the context of the nineties itself, without hindsight, it could seem like history had ended.

Tighe-breaker.

This sense of stillness arguably reflected a cultural anxiety as much as a political one. Even after history seemed to start moving again in the early twenty-first century, art and fashion still seemed frozen in place. Kurt Anderson acknowledged this just over a decade after the beginning of the new millennium:

Since 1992, as the technological miracles and wonders have propagated and the political economy has transformed, the world has become radically and profoundly new. (And then there’s the miraculous drop in violent crime in the United States, by half.) Here is what’s odd: during these same 20 years, the appearance of the world (computers, TVs, telephones, and music players aside) has changed hardly at all, less than it did during any 20-year period for at least a century. The past is a foreign country, but the recent past—the 00s, the 90s, even a lot of the 80s—looks almost identical to the present. This is the First Great Paradox of Contemporary Cultural History.

With all of that in mind, it makes sense that 11:59 should make a point to set its flashback sequences nineteen months ahead of its broadcast date, comfortable in the knowledge that nothing radical would have changed in the intervening time.

A vision of the future.

In some ways, it is worth reflecting on this attitude towards progress and development. Even in the context of the Star Trek franchise, it could feel like Voyager had given up on any sense that things might evolve or grow. In 11:59, the show predicts a near future that looks functionally identical to the present day. While that snapshot might be accurate in the jump from May 1999 to December 2000, it should be noted that would probably have felt inaccurate in a jump from May 2000 to December 2001.

11:59 assumes that the world is stable and static, even in the short and medium term. Contrast this with the more dynamic projections that the original Star Trek made about the years following the sixties; Space Seed felt comfortable predicting a third world war in the nineties, while The Changeling predicted the launch of a hyper-advanced space probe only two years into the twenty-first century. Some predictions were even bolder, Tomorrow Is Yesterday confidently (and correctly) predicted a moonlanding only two years after broadcast.

“You know, you think they probably would have dropped the “Gate” after the mass suicide, but what do I know?”

To paraphrase President George W. Bush, it seems as though the future was better yesterday. While Star Trek confidently predicted massive changes coming within the lifetimes of the audience, Voyager struggles to conceive of a world that can change in any meaningful way. In some ways this reflected a broader cultural anxiety, as Brendan Howlin argued:

For many generations, there has been a social contract. That contract meant that every family could believe in one simple idea. Work hard, and your children will have a better life than you. Work hard and the future will be better. That was a fair deal. But for the first time in generations, people no longer believe it to be true. They feel afraid for their children. They worry they will have to emigrate; and that they won’t be able to afford a home. Young people in their 20s wonder: will they have job security; or a decent quality of life; or a health system that works; or a roof over their heads.

In the late nineties, there was a sense that American voters were less optimistic about the country’s future, less hopeful for meaningful progress to be made. There was an increasing sense that the future would not be any better for the next generation or the generation after that.

Futures past.

This might explain why the Star Trek franchise turned its gaze backwards after the end of Voyager, with the prequel series Star Trek: Enterprise and the reboot franchise Star Trek. It was harder and harder to imagine a brighter future. Instead, it seemed like the best thing that the franchise could do was to engage in a retro futuristic nostalgia, to evoke a time when the future was a source of hope and optimism rather than to expand into a new future.

These forces were stirring within the franchise even before the prequels and reboots. Star Trek: First Contact represented a very literal trip back to the roots of the franchise, an exploration of the franchise’s internal history. Voyager had embraced a very retro sci-fi aesthetic in episodes like Phage, Cathexis, Faces, Tuvix, Innocence, Rise and Bride of Chaotica! In many ways, the series harked back to a retro fifties aesthetic embodied by episodes like Lifesigns or Warhead. The Star Trek franchise might not have begun moving back, but it was looking in that direction.

Back to the past.

Still, even if Voyager was not moving backwards, it certainly was not pressing forward. Voyager believed that the future was static, that it flowed organically from the present and that it could never be disrupted or altered. This was reflected in a number of different was, most notably in the strong belief that Voyager could effectively continue to tell Next Generation stories for seven more years, without ever evolving or growing. Even the production design of the series was very clearly an extension of The Next Generation more than anything unique or innovative.

Even in the context of the fictional universe itself, episodes like Future’s End, Part I, Future’s End, Part II, Timeless, Relativity and Endgame were built around a future in which the Federation and Starfleet were largely unchanged or unchallenged. These were not futures in which the Borg or the Dominion (or other entities) posed an existential threat to the Federation. Instead, there was an understanding that while particulars might change, such as the circumstances of individual lives, the trappings of the status quo would endure.

The Seven Wonders.

In theory, Kathryn Janeway was leading her crew on a journey travelling in a straight line. In reality, Voyager often seemed to be frozen in place. This reflected a broader cultural malaise. More than a decade and a half after the end of the nineties, Jason Farago reflected on this sense of cultural freeze:

For the political theorist Francis Fukuyama, history ended in 1989 – the big questions had all been answered, and the ‘90s were the first decade of a final era of democratic capitalism. By the start of the 21st Century, of course, Fukuyama’s thesis was brutally discredited, and endless crisis has brought history roaring back to life. But if we cannot speak of an end of history, can we perhaps speak, in a Fukuyaman sense, of an end of culture? Art will continue to be produced forever; that isn’t in doubt. But the regular succession of periods and movements that typify art history might be done for – and the ‘90s may turn out to be much more than a point on a timeline, but the first decade of a much, much longer era of stasis.

In 2012, art historian Lars Bang Larsen reflected that the nineties “haven’t yet found their closure.” He was speaking in artistic terms, but it underscores a sense of how eternal the decade seems. (The first United States President of the twenty-first century was the son of the President at the start of the nineties; the most recent election found the First Lady of the nineties running.)

A cold reception.

In some ways, this sense of stasis is reflected in the plotting of 11:59, in the romance between Henry and Shannon. Shannon explicitly spells it out during their conversation at the climax. “I’m stuck in the future, you’re stuck in the past,” Shannon explains. “But maybe we could get unstuck in the present.” The present is reflected as a maintenance of something resembling the status quo as the future beckons. Shannon decides to stay in Indiana, and to help Henry maintain a sense of continuity by opening a book store inside the Millennium Gate.

This is very much how 11:59 views progress and evolution, reflecting how Voyager sees the future. Voyager imagines that characters and situations can remain in stasis, even as the world around them changes, a decidedly paradoxical view for a series about a show featuring a crew travelling seventy thousand light years home. Indeed, there is a sense that 11:59 reflects a strong impulse within Voyager to stop pushing forward, to settle down.

On the road.

Shannon O’Doherty is introduced as a wanderer, explicitly parallelled with Janeway. Shannon narrates exposition to herself while driving in her car, a contemporary twist on the narrative convention of “Captain’s Logs.” She is introduced sipping a large cup of coffee, recalling Janeway’s own addiction to caffeine. Like Janeway, Shannon is a character on a long journey. In 11:59, she is trying to get to Florida. However, the episode suggests that she has always been a traveller at heart.

Introducing herself to Henry, she states, “I love to see places I’ve never been, try new things. I’m kind of an explorer.” Henry quips, “That station wagon of yours doesn’t exactly look like a sailing ship.” Stopping just short of winking at the audience, Shannon replies, “It’s a rocket ship.” The other characters acknowledge Shannon’s hermetic existence. “You don’t have to live like this,” Moss tells Shannon at one point. “Borrowing money, sleeping in your car.” Henry describes her as “exploring the Midwest in an ailing station wagon.”

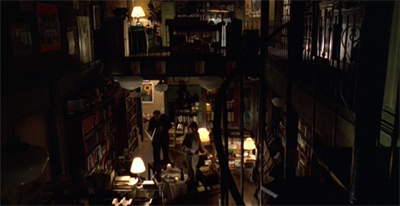

Future proof.

Although Shannon continually pushes forward, advocating for exploration and adventure, the episode’s sympathies lie with Henry’s desire to stay put and to put down roots. Henry makes a compromise at the end of 11:59, but it is largely token. He trades the book store on the street for the book store in the Millennium Gate. “I suppose I could re-open my shop in that monstrosity you want to build,” he reflects. It is entirely possible that Henry never actually leaves Indiana. In contrast, Shannon surrenders her entire way of life in order to settle and find stability.

Shannon finds peace and tranquility in and around Portage Creek. Perhaps reflecting Voyager‘s more conservative impulses, that sense of fulfillment is reflected in a picture of her with her extended family. Indeed, the closing scene seems to consciously parallel this image with Janeway’s day to day life, as Shannon plays dutiful commanding officer, instructing a younger member of the clan, “Knock it off, Kieran. That’s an order.”

It all past so quickly.

This parallel at the heart of 11:59 is striking, suggesting almost an allegory for Voyager itself. Paradoxically for a show about a long journey home, 11:59 seems to be suggesting that Janeway has found her own family on the ship and that this extended voyage has afforded her to settle down into the role of matriarch that Shannon found so comforting. There is no small irony in all of this. On the surface, Voyager appears to be the establishing scene of Shannon driving down long dark highways. In its heart, Voyager longs to be the closing scene of a family rooted firmly in place.

Of course, this is not the only aspect of 11:59 that feels perfectly attuned to Voyager‘s tone and aesthetic. In many ways, 11:59 is a story about the malleability of memory and the distortion of history. It is a companion piece to other episodes like Remember, Distant Origin and Living Witness, stories about how easily the past can be warped and bent, how fragile the historical record is, how easy it is to lose a tangible connection to the truth of what really happened.

Not exactly firing on all the thrusters.

Producer Brannon Braga framed the episode in these terms while talking to Cinefantastique:

“We wanted to do a show dealing with the millennium, before the millennium came. We wanted to tell a story of Captain Janeway’s great, great, great, great, great, great grandmother, played by Kate Mulgrew. At the same time, we tell a little story with the real Captain Janeway talking about this relative. We see how what Captain Janeway thinks happened was very different from what happened. It’s a story about history, and how history can be misinterpreted. Ultimately, it’s a very unique off-concept episode. It’s a real acting tour de force for Kate Mulgrew.”

This notion of historical distortion is a recurring theme across the seven seasons of Voyager, reflecting a millennial anxiety about the potentially corrosive power of postmodernism.

Not everybody’s cup of tea.

As much as Voyager takes the future for granted, the series repeatedly suggests that the past is up for grabs. While Future’s End, Part I and Future’s End, Part II reveal the existence of a twenty-ninth century version of Starfleet, the two-parter presents a threat centred in the late twentieth century. Characters threaten to attack the history of Voyager in episodes like Relativity and Fury, even while episodes like Shattered and Before and After insist that the ship will have a relatively stable and productive future.

Even in the context of 11:59, the future seems a lot more stable than the past. The teaser establishes that the Millennium Gate will be built, suggesting that there is nothing that Henry or Shannon can do to stop it. Even in the context of the flashbacks, it is made very clear that the Millennium Gate will be built somewhere, even if it is not built in Portage Creek. “If we can’t work out an arrangement in Portage Creek, we’ll have no choice but to select another location,” Moss explains to reporters at one point.

History lesson.

Meanwhile, Henry frets about the possibility that the past might be lost or erased. “You, you just can’t, you can’t bulldoze this town away,” Henry warns Moss. “This, this is our heritage. This is our past.” Shannon frames the debate in even more personal terms. “Your son tells me that your bookstore’s belonged in your family for generations,” Shannon explains. “That you’ve never done anything else.” Henry nods, “Yes, that’s right.” As with the debate about settling or travelling, it feels like 11:59 is firmly on Henry’s side in this debate.

After all, the Millennium Gate coincides with a host of lost history. Janeway mistaken believes that Shannon was an engineer who pushed the boundaries of science. “At that time, she was still in the space programme, but she’d also become something of an entrepreneur,” Janeway tells Neelix. “I believe she was asked to join the project by the governor of Indiana. He wanted her expertise on recyclic life support systems. The way my aunt Martha, tells it they flew her in on a private aircraft.” The teaser puts paid to that theory.

A rolling stone gathers no Moss.

Indeed, the framing device makes a point to establish a thematic connection between 11:59 and Living Witness, the late fourth season off-model episode. When Chakotay shows up with a report, Janeway muses, “Let me guess. The holographic engineer is having problems with her programme. Neelix, the Cardassian cook, is low on supplies. Seven of Twelve is regenerating and Captain Chakotay is doing just fine.” She reflects, “Just wondering how they’ll piece together our lives a few hundred years from now.”

She suggests that this distortion of the historical record is already taking place. “I’ve gone through dozens of histories written about twenty first century Earth, all of them biased in one way or another. The Vulcans describe First Contact with a savagely illogical race. Ferengi talk about Wall Street as if it were holy ground. The Bolians express dismay at the low quality of human plumbing. And human historians? Exact same story. Every culture saw it a different way.”

Observing history from the sidelines.

In its own way, 11:59 suggests that the reality of twenty-first century Earth is as fuzzy as the origin of the Voth in Distant Origin or the details of the conflict between the Vaskans and the Kyrians in Living Witness. Once again, this feels like a concern very specifically rooted in the cultural context of the nineties. As defining earth-shattering events like the Second World War and the Holocaust slipped from living memory, as Holocaust Denial and conspiracy theory became more mainstream, the nineties suggested an anxiety about the malleability of history.

In keeping with the interests of writer Joe Menosky, 11:59 even makes a couple of small nods towards conspiracy theory. Henry’s language evokes the rhetoric associated with strands of nineties conspiracy culture, decrying the “propaganda” published by “the invaders” who have conspired with “the City Fathers” to effectively usurp the citizens of this small town. Menosky is a writer interested in narrative and story, and conspiracy theories tend to pop up in his Voyager work; Future’s End, Part I, Future’s End, Part II, Latent Image, The Voyager Conspiracy.

The future is now.

At the same time, there is a clear feeling that Menosky is an awkward fit for this particular script. The writer acknowledged as much when discussing the episode with Cinefantastique:

“Ultimately, to me, it was a lot of domestic scenes, which I am not interested in writing. Our original inspiration for it was to do it without the hard science fiction, but more than anyone, I wish that we had had something of that element in to drive the plot. Rick Berman called to say he loved it I just kind of shrugged. You just never know.”

Joe Menosky is easily one of the best science-fiction writers to work on the Star Trek franchise, as scripts like Darmok attest. However, he is an awkward fit for this script.

Maps to the stars.

The Star Trek franchise has a very distinct production style. This makes a great deal of sense, given the building of a sprawling fictional universe on a television budget. In particular, Star Trek dialogue is very different from the dialogue seen on many contemporary television shows. More than that, the actors who tend to thrive on Star Trek might feel out of place in a more naturalistic setting, because acting in a Star Trek story involves all manner of projection and uncanniness.

As a rule, the Star Trek franchise can seem very theatrical. This is reflected in the way that writers approach scripts, favouring long conversations between characters using extended metaphors and lots of grandstanding. This is reflected in the production design, even outside of episodes like The Empath or The Thaw, where the actors move through sets that look absolutely nothing like anything within the audience’s real-world frame of reference. This is reflected in the performances, many of which exist in the shadow of William Shatner’s heightened delivery.

“Time for some sober reflection on last weeks adventure.”

Many Star Trek episodes would work very well as stage plays; in fact, many have been adapted. Part of the reason that The Next Generation worked so well was because it gave a stage with the highest production values to a Shakespearean actor of the caliber of Patrick Stewart. Many of the best episodes of Deep Space Nine feel like they could be performed at some weird coffee shop somewhere; Duet, Family Business, Doctor Bashir, I Presume, Waltz, In the Pale Moonlight. Tellingly, several Deep Space Nine actors have stage plays that they perform at conventions.

All of this makes it difficult to set a Star Trek episode in the present day with characters who are meant to exist in a world close enough to the real world. There are certain Star Trek conventions that do not translate well so something approximating the real world. 11:59 brushes up against these limitations, particularly in terms of dialogue. There is something very dissonant in watching characters who are supposed to be grounded in the modern day talking like they are appearing in a Star Trek episode.

He could never hold a candle to Chakotay.

This is most obvious with Henry Janeway, who talks like every old man in a Star Trek episode ever. Like Paul Stubbs in Evolution or Ira Graves in The Schizoid Man, Henry is an individual who loves to demonstrate his intelligence and his cantankerous qualities through very flowery grandstanding dialogue laced with awkward exposition. However, while Stubbs and Graves were providing necessary plot information through their clunky exposition, Henry’s references to classical civilisation feel stilted and forced.

Henry’s son is named “Jason.” His book store is named “Alexandria Books.” These details alone would establish his affection for Greece and Rome. However, the script pushes further. When Shannon arrives in his book store, Henry reflects, “Zeus himself watched over travellers. We should follow his example.” When Shannon asks for coffee, Henry responds, “Decaf. Not exactly the nectar of the gods.” Explaining his battle against a corporate goliath, Henry vows, “This time, Rome withstands the barbarians.” All of this happens within Henry’s introductory scene.

Henry is a Classic character.

Shannon does not come across much better. Menosky tries to create a sense of parallels between Janeway and Shannon, which makes sense; both characters are portrayed by Kate Mulgrew, so it makes sense to mirror them. However, a lot of this consists of having Shannon behave like she is a twenty-fourth century starship captain while cruising the dark roads of “the great state of Indiana.” She talks to herself to deliver exposition to the audience, and to make subtext text, in a manner that feels incredibly forced in the context of a grounded story.

Even the big scenes between Henry and Shannon feel more like an awkward stage play than anything unfolding in the real world. In particular, Shannon and Henry deliver thematic and emotional exposition in a way that does not reflect how people talk to one another, interacting almost as abstract concepts rather than human beings; Shannon represents the future, Henry represents the past. However, neither of them feels like flesh and blood human beings, with any psychological complexity or depth.

Who we are in the dark.

To be fair to 11:59, Kate Mulgrew does very good work with material presented to her. As Menosky confessed to Cinefantastique:

“Kate really loved playing a character that was not herself. She plays the founder of the Janeway clan, but she’s a very reluctant hero, and a very damaged hero. She walks around with her hands in her pockets, and her head slightly bowed. She’s a more withdrawn and vulnerable person than you can ever imagine Janeway being. It was quite nice to see her do that performance. David Livingston, who is a marvelous director, did it on the New York Street on Paramount lot. They brought in tons and tons of snow and blew it all over the street.”

Mulgrew lends Shannon O’Doherty a sense of dignity and vulnerability, while also making it clear that Shannon shares her descendant’s strength of character.

They have their next holiday booked.

Mulgrew is a horribly unrated performer, particularly among the Star Trek leads. A large part of this is because Voyager struggled to define the character of Janeway. Over the course of the show, it frequently seemed like the writers were trying to amalgamate three different characters into a single lead character. Mulgrew has talked at length about her own efforts to assert authorship of the character during Jeri Taylor’s tenure as showrunner, while Brannon Braga tried to reinvent Janeway as a no-nonsense take-no-prisoners badass.

It is very difficult to accept that the versions of Janeway appearing in episodes like The Cloud, Macrocosm and Coda could be the same individual, despite Kate Mulgrew’s commitment to each individual script on its own terms. These wild swings even take place within the same season. Is Janeway a maternal figure to her crew as suggested by episodes like Dark Frontier, Part I, Dark Frontier, Part II and The Disease? Or is Janeway a tough situationalist leader, as suggested by her logic and decisions in Nothing Human or Latent Image?

Feels like going home.

However, Mulgrew is a great performer. After all, she would earn an Emmy nomination for her work on Orange is the New Black more than a decade after Voyager ended. Even within the context of Voyager itself, Mulgrew is easily one of the best performers in the cast, as demonstrated by episodes like Concerning Flight or Counterpoint. Unlike Voyager‘s other breakout performers, Robert Picardo or Jeri Ryan, Mulgrew’s abilities are often demonstrated in spite of the material rather than in harmony with it.

That said, Mulgrew always had something of a strained relationship with Voyager, particularly following the introduction of Jeri Ryan as Seven of Nine in Scorpion, Part II. There was a clear tension between the two performers, which made the fourth season very difficult for everybody involved. Although those tensions had simmered down going into the fifth season, there was a clear sense that Kate Mulgrew was not entirely happy working on Voyager.

Picture perfect.

She wanted out, and decided to use critics to convey her message. First, however, she issued a disclaimer, to make it clear that her actions were not comparable to David Caruso’s. “I don’t want to see words like petulant or upset in your stories. I feel so privileged and happy to have been a part of this show.”

She loves everything about Star Trek: Voyager, she said. Well, almost everything. “I love my character and this company, the cast, the crew. After five years, there’s not a bad apple in the bunch.” Then she added a qualifier. “Well … Jeri Ryan [who plays Seven of Nine] is new, so I’d put her aside.”

Even ignoring the statements made by Mulgrew, Ryan, and their co-stars in the years since Voyager went off the air, that is hardly the most subtle of parting shots.

Chewing it over.

It is interesting to wonder what might have happened if Mulgrew had decided to leave at the end of the fifth season. It would have been a massive shake-up for the show. No Star Trek series had ever lost its lead character. Leonard Nimoy had insisted on killing off Spock in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, but returned in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. Nobody seems entirely sure whether assimilating Picard at the end of The Best of Both Worlds, Part I was a contractual plot, but Patrick Stewart returned the following season.

UPN advocated to kill off the character of Jonathan Archer in Zero Hour. Manny Coto expressed an interest in the possibility of killing off a series lead, but Rick Berman and Brannon Braga ultimately decided against it on the grounds that it would represent a massive vote of low confidence in the series itself. As such, losing Kate Mulgrew would probably have been devastating to Voyager.

“Oh, we’re in this episode too!”

Luckily, that did not come to pass. The crisis was resolved almost as quickly as it had unfolded, with Paramount working very quickly to get Mulgrew on-message about her decision to stay:

UPN officials sought for comment were evasive, although network CEO Dean Valentine was sarcastically dismissive. “Really? She said that? Well, we’ll miss her,” he said in an I-couldn’t-care-less tone. Then he twisted the knife: “I guess this means a promotion for Jeri Ryan.”

Apparently Valentine’s cavalier attitude was just for the press. His conversation with Paramount brass must have taken a different tack. The studio sprung into action at warp speed. Star Trek is a billion-dollar franchise for Paramount, and Voyager is the highest rated series on UPN, which is partially owned by the studio. Mulgrew was tugging on Superman’s cape.

Critics who had interviewed her started getting backtracking calls in their hotel rooms long after business hours. A senior executive at Paramount, John Wentworth (personally, not his secretary), came on the line and said, “Kate Mulgrew would like to talk to you.”

A clearly chastened Mulgrew then was handed the phone with the Paramount honcho standing by. “I shared my heart with you today,” she began. “Let me clarify some things. I have no intention of leaving this show before its time. Although I’m contractually bound to a sixth season, the door is wide open to a seventh.”

Even the most casual of observers would have noticed that things were not happy behind the scenes on Voyager.

A by the book romance.

Ultimately, Mulgrew would stick around for the sixth season and would sign on an extension for the seventh season. Indeed, nobody watching the show would ever be left in any doubt about the possibility of Janeway surviving; neither cliffhanger ending to Equinox, Part I or Unimatrix Zero, Part I made a point to single the character out for peril, instead throwing several members of the primary cast into fairly bland threats. There was never any uncertainty Janeway would get her crew home, and would survive the journey.

This was not the only time that the character of Janeway brushed up against the possibility of a tragic ending. Endgame features the assimilation and death of a future version of Kathryn Janeway, but her present day counterpart lived on to make a small appearance as a senior admiral in Star Trek: Nemesis. The relaunch novels would make a bold decision to kill off the character of Kathryn Janeway, but would very promptly walk back that decision.

Flickering romance.

During the sixth season, Mulgrew would acknowledge this near-miss in an interview with Starlog, and insist that she was much happier working on Voyager than she had been:

“If they had said to me, ‘We really don’t care,’ I may have considered leaving,” she responds. “I was under contract already for the sixth year and I intended to honor that contract. I’m only talking about conversations and negotiations for the seventh season. It really involved my happiness quotient. In many ways, I set the tone on the set. My mood and my approach are very important, and I think there’s nothing worse than a professional actress who is unhappy because she misses her husband and children. But [Berman and Braga] realized that. And if I may say so, they were not only gentlemen about it, but very gracious. I am much, much happier now.”

Even allowing for this happy ending, it is clear that Voyager was not a particularly healthy or happy environment for those working on the series.

Looking ahead.

11:59 doesn’t quite work. It is clumsily structured and awkwardly written, with the script often struggling against the boldness of its core idea, setting a Star Trek episode in the present day without resorting to conventional plot devices like time travel or holodeck technology. Still, 11:59 is an ambitious episode of Voyager, and it would seem churlish to condemn Voyager for an ambitious misfire. Sometimes, ambition pays off. Other times, ambition is not enough to get an episode across the line.

11:59 is an experiment that doesn’t work, but that doesn’t make it unworthy.

Filed under: Voyager | Tagged: 11:59, future, history, janeway, Kate Mulgrew, memory, millennium, star trek, star trek: voyager, voyager |

>Mulgrew is a horribly unrated performer

…Maybe, if we’re talking Voyager: After Hours.

>Rick Herman called to say he loved it

Ben, one of your relatives?

Wasn’t there also an incident (between seasons 2 & 3?) where Mulgrew wanted to quit but changed her mind? I seem to recall her referencing it in Communicator about a year after she changed her mind.

> Voyager: After Hours.

Good catch, corrected!

I don’t know about a S2/S3 departure, but I do know the cast weren’t particularly happy in S2. There’s a great Starlog interview where they just tear into the writing of the show as a group.

Overall, this episode doesn’t hold up. It was already kind of rotten when it aired, but now it’s worse. Every week we hear of a new football stadium springing up and draining our municipalities of hundreds of millions. The retail apocalypse. The well-documented failures of urban planning. Postmodern architecture (even republicans hate it!) The list goes on, and on.

Deep Space Nine already did this episode with “Progress”, and while that story was rotten, too, they were at least trying to carve out their niche as a morally ambiguous Trek series.

The ending to this 11:59 is like Meg Ryan walking around a soulless corporate bookstore in “You’ve Got Mail” and deciding her family owned bookstore deserved to die.

Christ.

I agree. There is a distinctly American vein of capitalist cheering running through this episode. In a decade where Walmart was consuming small downtowns, it seems a bit much to have Janeway fighting for a huge retail outlet mall. The bookstore owner’s opposition is framed as quaint, but it’s also a huge strawman argument. He’s “living in the past”. He is a businessman. He only reads about the past, but not philosophy. Being into the past means he also doesn’t travel.

There’s no mention of the ecological damage being done here, of the fact that if the project is a self-contained biosphere they could build it in Nevada, Alaska, or Antarctica just as easily. If this episode is a critique of post-modernism, it is a ringing endorsement of modernism, arguing that technological progress will save us all.

Star Trek always fails hardest when it depicts near-future scenarios that an almost immediately disproved. It revealed the disturbingly hollow nature of their purely materialist view of life – with humanity devoid of any spirituality.

However, there is an unintentional prescience here regarding the collapse of social fabric and economic well-being in the US Midwest. Rather than argue for education and a move away from pure individualist capitalism, the episode argues for a doubling-down on corporate mega-projects and a re-colonization of the land. Rather than move a couple towns over, the bookstore owner acquiesces to move his business into an artificial habitat, to kneel to the greed of a mega-corporations obliteration of his community and exist in a hermetically sealed mechanism. He gets assimilated, in a way.

There are also echoes of what Elon Musk has been doing in Boca Chica.

I become increasingly concerned in adulthood that the general ethos of Star Trek – especially later the series – is inherently vacuous: An American fever dream.