Fantastic idea for a movie. Terrible idea for a proctologist.

– the Doctor’s ten-word review of Fantastic Voyage

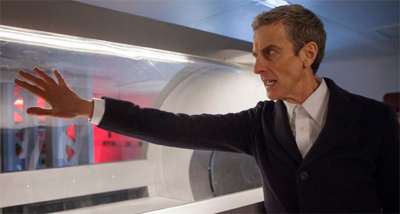

If you’re looking for a writer to collaborate with on a “dark Doctor” story, it would seem that Phil Ford is your man. Phil Ford collaborated with showrunner Russell T. Davies on Waters of Mars, the penultimate story of David Tennant’s tenure. Here, he finds himself writing with showrunner Stephen Moffat on the second story of Peter Capaldi’s tenure. So he also does symmetry where Scottish Doctors are involved. That’s a pretty solid niche, as far as Doctor Who script-writing goes.

Both Waters of Mars and Into the Dalek are stories that serve to problematise the Doctor; but each does it to a different purpose. Waters of Mars was positioned as the second-to-last story of the Davies era. It serves as the point where the Tenth Doctor’s hubris reaches massive proportions and explodes. It serves, in a way, as the justification for his departure in The End of Time. In contrast, Into the Dalek serves to solidify a character arc that was hinted at in Deep Breath, the Twelfth Doctor’s existential crisis.

Into the Dalek is the source of the much-hyped exchange between Clara and the Doctor about the latter’s nature as a Steven Moffat protagonist. “Clara, be my pal and tell me: am I good man?” the Doctor asks. The best that Clara can manage is, “I don’t know.” The Doctor responds, “Neither do I.” This isn’t the first time that the show has dared to present a morally ambiguous lead character. Colin Baker’s infamous Sixth Doctor comes to mind, but Christopher Eccleston’s Ninth Doctor was arguably a more successful attempt to give the audience an ambiguous Doctor.

As such, Into the Dalek cannot help but invite comparisons to Eccleston’s morally charged confrontation a broken Dalek in Dalek. Sadly, it’s not a comparison that does Into the Dalek any favours.

Still, the idea of defining the Doctor against the Daleks is not new. The Daleks first appeared in the show’s second serial. They were the enemies that helped Patrick Troughton transition from William Hartnell. Into the Dalek admits as much, acknowledging that the Doctor only properly defined his identity as “the Doctor” when he landed on Skaro:

See, all those years ago, when I began. I was just running. I called myself the Doctor, but was just a name. Then I went to Skaro. I met you lot. And I understood who I was. The Doctor is not the Daleks.

There’s a sense that – as with the discussion of age in Deep Breath – the show is writing its own external narrative into the show. Doctor Who is a show that has always winked at the audience, but the Moffat era is particularly self-aware and engaged with the show’s production history.

The Daleks were the first monsters. The defined the show’s idea of “monsters.” On its creation, Doctor Who had originally been conceived as an education show without silly science-fiction monsters. Now it is impossible to imagine the series without them. As such, the show only found its identity until the second serial, The Daleks. Despite the fact that the show didn’t want to do silly monsters, the genie couldn’t be put back in the bottle. Ratings were high and the public was enamoured. In a real sense, the Daleks made the show.

It’s impossible to imagine Doctor Who without them. When the show went through its first traumatic regeneration, an event without precedent, the producers counted on the Daleks to carry the views over. When the Daleks identified Patrick Troughton as the Doctor in The Power of the Daleks, that meant that the viewers could accept him as well. For better or worse, the Daleks tower over the mythos. Even the Cybermen cannot expect to get title billing in episodes centred around them. (As Dark Water and Death in Heaven demonstrate.)

Stephen Moffat acknowledges the importance of the Daleks even more than Russell T. Davies did. For all that the execution was awkward, the idea behind Victory of the Daleks was a classic. Moffat chose to pit Matt Smith against the Daleks sooner rather than later, knowing that it was best to get this step out of the way cleanly and efficiently. Smith faced the Daleks in his third episode. This time, however, the Daleks were counting on the Doctor to identify them, a rather wry and ironic twist on The Power of the Daleks.

The same logic seems to be at work in Into the Dalek. Peter Capaldi finds himself coming up against the Daleks in his second episode. This time, the Daleks are very clearly and very carefully staring into him. The Daleks no longer just identify the Doctor, they identify with him. Times have changed so much that Into the Dalek isn’t about the Daleks naming the Doctor and validating the new actor. This time, the Doctor and the Daleks actually intermingle. “No, you don’t understand,” the Doctor protests, “you can’t put me in there.”

At the start of Into the Dalek, the Doctor ventures inside the mind of a Dalek. At the climax, the Doctor melds with the Dalek. For a brief section of the episode, the Doctor and the Dalek are of one mind. “You are a good Dalek,” the Dalek at the centre of Into the Dalek observes, as it gets a glimpse into the mind of the Doctor. For all that the Doctor talks about wonder and majesty and beauty, the Dalek sees genocide and pain and suffering and hatred. The Doctor is just as much a killing machine as his enemy.

Towards the end of the episode, the Dalek at the centre of Into the Dalek plays back various memories and experiences. The majority of those seem to be drawn from the Davies era. The destruction of the Dalek sphere in Journey’s End, the attack on the Valiant in The Stolen Earth, the Dalek fleet in The Parting of the Ways. Moffat seems to be raising the spectre of the Davies era, where the Doctor was prone to boats of genocidal rage at the very mention of the word “Dalek.” The Dalek in question is even affectionately nicknamed “Rusty.”

It seems like Moffat is treading back over old-ground here. The first Dalek episode of the revived series, Dalek, explored the weight the Doctor’s hatred for the pepperpot dictators. Christopher Eccleston was perhaps the first actor to convince an audience that they should be afraid of these iconic killer mutants. The Ninth Doctor responded to the pain and suffering of the Dalek with anger and hatred and contempt. “You would make a good Dalek,” the Dalek at the centre of that story reflected, the line referenced here.

Dalek fit well in the context of the Davies ere. Davies wrote a morally ambiguous version of the Doctor. The Ninth Doctor was a character dealing with post-traumatic stress, trying to cope with the fact that he had committed genocide. The Tenth Doctor was a character pretending that he had worked through all that anger and hate. During the Davies era, the Doctor was capable of incredibly short-sighted and selfish and hypocritical decisions. Even his refusal to commit genocide in The Parting of the Ways is questionable.

The Tenth Doctor’s first adventure saw him unilaterally toppling an elected leader in The Christmas Invasion, an act that set in motion events that would (in a rather convoluted manner) lead to his regeneration. In The Sound of Drums, he refused to murder the Master, even as the Master plotted to kill hundreds of millions of lives and enslave mankind itself; even afterwards, he refused to consider handing over the Master to human justice. In short, something like The Waters of Mars seemed inevitable.

The problem is that Moffat has worked very hard to remove that sense of ambiguity from the character. The Eleventh Doctor could still make mistakes with terrible consequences, but these seemed less likely to be rooted in arrogance and hubris. He just was not good at seeing obvious problems that could arise as a result of his decisions, and not necessarily good at understanding people. However, the Eleventh Doctor did make a conscious effort to get better at that as he went.

Indeed, Moffat brought the Eleventh Doctor a full circle. In The Eleventh Hour, the Doctor caused considerable psychological harm to Amelia Pond by abandoning her while he ran way in the TARDIS; he created a seventeen-year absence that caused considerable damage to the young girl. In The Time of the Doctor, the Doctor decided to stay on Trenzalore when Barnabus asked if he was planning to leave. It seemed like the last decision that the Eleventh Doctor made was an attempt to remedy his very first mistake.

That said, the Twelfth Doctor is a new take on the character, with a new character arc. Just as the Ninth Doctor was distinct from the Tenth Doctor, and the Tenth Doctor was distinct from the Eleventh, the Twelfth Doctor must be allowed to follow his own character arc. Perhaps the Twelfth Doctor is a little more ruthless and ambiguous than his predecessor; perhaps all the work that the Eleventh Doctor did to make himself a better person has been lost to history, washed away in a bath of regeneration energy.

Still, Into the Dalek airs less than a year after Moffat’s gigantic fiftieth anniversary Doctor Who showcase, The Day of the Doctor. In that episode, Moffat had made a very convincing argument that the Doctor should be incapable of genocide. The Doctor would not deploy a weapon of mass destruction. The Doctor would not do something truly horrific and unforgivable. The Doctor is not a tortured anti-hero. The Day of the Doctor revealed that the Doctor had not destroyed Gallifrey at the end of the Time War, thus wiping a significant stain from the character’s soul.

As such, Into the Dalek does feel a little bit like a retread of a familiar character beat. It is something that the show has done before; quite recently, too. Moffat is a big fan of the character arc that sees a great man trying to become a good one. It makes sense that the Twelfth Doctor would begin his tenure with no small measure of self-doubt and insecurity. However, Into the Dalek feels like something that has been well laid to rest at this point. We know this argument. We’ve seen it play out.

The idea of “Doctor-as-Dalek” is much better suited to the Ninth Doctor than the Twelfth Doctor. It is an argument that seems much more applicable to the Doctor who regenerated after destroying Gallifrey, as opposed to the Doctor who regenerated after saving it. That’s not to say that the Doctor’s hatred of the Daleks isn’t worth exploring, it’s just that there really should be more to be said than observations made almost a decade ago. Moffat has worked very hard to cast off a lot of the trappings of the Davies era, so it feels strange to revive this one.

At the same time, Into the Daleks at least implicitly acknowledges that the Doctor has been trying to wipe out the Daleks for quite some time. The sequence where Capaldi integrates himself with the Dalek harks back to the most iconic scene from Genesis of the Daleks. In that adventure, the Fourth Doctor was unable to connect two wires in order to exterminate the Daleks. Here, the Twelfth Doctor connects two wires in order to save a Dalek. It’s a nice twist on some of the show’s most memorable imagery.

It is a shame that Into the Dalek feels like it’s covering old ground, because the show works quite well on its own merits. The Davies era had a tendency to go bigger and larger with Dalek stories. In The Parting of the Ways, the Daleks threatened Earth in the future; in Doomsday, the Daleks threatened Earth in the present; in Journey’s End, the Daleks threatened reality itself. In contrast, Moffat has been more interested in telling weird or sideways stories where the Daleks don’t serve as omnicidal threats the fabric of existence.

To be fair, this is in keeping with the more experimental tone of the Moffat era as a whole. The Davies era was very consciously attempting to re-imprint Doctor Who on the national consciousness. Davies’ Doctor Who was really about introducing an entirely new generation to the concept of Doctor Who, explaining how the show works and the world that it explores. Those four seasons lay a lot of the essential groundwork, beautifully distilling forty-odd years of continuity into sixty episodes.

One of the benefits of taking over from Russell T. Davies is the freedom to experiment. Now that modern television viewers know what to expect from Doctor Who, now that the core concepts are entrenched, Steven Moffat can play with them. This is particularly evident in the Dalek-centric episodes of Moffat’s tenure. Moffat is decidedly disinterested in the Daleks as a threat to the universe at large. Of his season finalés, the Daleks play minor roles in both The Big Bang and The Wedding of River Song, as if appearing out of contractual obligation.

In contrast, the Dalek-centric episodes of the Moffat era are largely driven by high concepts and crazy ideas. In Victory of the Daleks, the show completely redesigns the iconic pepper pots; Mark Gatiss created five new Dalek designs with names like “Eternal Dalek”, concepts that were never fully expanded. In Asylum of the Daleks, the show introduced the concept of “human Daleks”, an airborne Dalek virus that could eat a person from the inside out. These are new ideas that push the Daleks in novel directions, much as the concept of “a good Dalek” does.

While this experimental approach hasn’t always paid off, it does make sense. After all, it’s hard to take the Daleks seriously when they are defeated so frequently. Moffat’s Dalek stories frequently have smaller scales. This allows the Daleks to win, or the episodes to end at a stalemate. The Doctor doesn’t need to wipe out the Daleks completely in order to ensure the universe’s continued existence. In Victory of the Daleks, the Daleks fight for survival; and they win. In Asylum of the Daleks, the Daleks manipulate the rules so that the Doctor helps them win.

Building on all of this, Into the Dalek takes the story to as small a scale as possible. The show features the Doctor leading a team inside a single Dalek. “It’s huge,” one of the soldiers accompanying the Doctor observes. “No, Ross,” another soldier responds. “We’re tiny.” With Into the Dalek, a single Dalek can become truly majestic and impossible and incredible. It is just a matter of looking at it from the right perspective. After all, Into the Dalek opens with its big space battle sequence before becoming a lot more intimate.

“It’s smaller on the outside,” Journey Blue remarks of the TARDIS, playing with the classic “it’s bigger on the inside” in the way that has become a minor recurring gag of the Moffat era. “Yeah,” the Doctor acknowledges. “It’s a bit more exciting if you go the other way.” This idea of size and perspective – mirroring the TARDIS – has become something of a theme of the Moffat era. In The Doctor’s Wife, Idris pauses to wonder if all people are bigger on the inside as well.

As such, the idea of doing Fantastic Voyage… but with Daleks is a very clever way of applying one of the core themes of Doctor Who to the Daleks. Into the Dalek dares to wonder if a Dalek could be bigger on the inside. It is a small episode packed with Dalek iconography, and appropriately enough features a riff on the Ninth Doctor’s confrontation with the Dalek Emperor in The Parting of the Ways. This time, however, it is a tiny Doctor addressing a regular-sized Dalek as opposed to a regular-sized Doctor addressing a giant Dalek.

After all, Doctor Who is a show frequently about the intersection of the epic and the intimate. The TARDIS is a vessel that is small on the outside and large on the inside, as the teaser points out to us once again. Clara works a day job as a teacher, while adventuring across time and space. She returns from an epic encounter with the Daleks to go on a date with Danny. Much as the Doctor opened up all of the universe to a shopgirl from the Powell Estate, Doctor Who makes something quirky and small seem incredible and vast.

Here, the Doctor is confronted with the possibility that the Dalek might actually be bigger on the inside – that it may be more complex than he would ever allow. The small wonder of a star being born is enough to stir the soul of a heartless killing machine. The Doctor is a Time Lord who rejected the teachings of his people so that he might appreciate the wonders of the universe. Is it so impossible that a Dalek might be able to do the same? Into the Dalek teases us with the possibility of “a Dalek so damaged its turned good.”

Naturally, the Doctor wonders what could have led the Dalek to this epiphany. It turns out that “Rusty” happened to see the birth of a star, an event that inspired the Dalek to see the beauty in the universe. More than that, it forced the Dalek to accept a new philosophy of existence. “Resistance is futile,” the Dalek advises the Doctor. “Life returns. Life prevails. Resistance is futile.” In essence, “Rusty” is a Dalek that has accepted the optimism inherent in Steven Moffat’s version of Doctor Who. Not only this once, everything lives.

“A good Dalek” is a fundamentally broken concept; like the hospital ship so broken that it no longer has no doctors. The obvious implication is that there could be a Doctor so damaged that he turned bad. Scripts like The Day of the Doctor make it hard to believe that Moffat could ever write a truly and irreconcilably “dark Doctor.” Moffat is, after all, the author responsible for the happiest ending of Christopher Eccleston’s one-season tenure in The Doctor Dances. However, Into the Dalek does give the Doctor just a little bit of an edge.

The Doctor cynically uses the death of Ross to guide the rest of the team to safety; accepting that he could not save the soldier, he rather coldly decided to exploit it. “I thought you were saving him,” Journey Blue shouts. “He was already dead,” he assures the rest of the group. “I’m saving us.” As the team find themselves floating in a vat of floating protein made from people – yes, it’s green – the Doctor is quick to explain how this is a tactical advantage. “Nobody guards the dead.”

As played by Capaldi, the Twelfth Doctor has a bit of an edge to him. “Do please keep crying,” he remarks to Journey Blue, after the death of her brother. He may not be a bad man, but he can certainly be unpleasant – he is not entirely sympathetic towards people; perhaps too caught up in his own suffering as the Ninth Doctor had been. Every Doctor except for the Third Doctor has had an awkward relationship with authority, but the Twelfth Doctor seems to have a particular disdain for soldiers, much like the Tenth Doctor in The Poison Sky.

“Crying’s for civilians,” he tells Journey. “It’s how we communicate with you lot.” This seems much more like the attitudes expressed by the Ninth or the Tenth Doctor towards military organisations than the attitude of the Eleventh. With the addition of Daniel Pink to the cast, it seems like Moffat is setting up an arc about post-traumatic stress and recovery. Given that Into the Dalek has to introduce Danny Pink while keeping him separate from the bulk of the action, mirroring him through Journey Blue is a clever move.

Undoubtedly, there is a lot of material to explore about the legacy of conflict and the damage cause by war, particularly in the wake of the Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, this does feel like ground that the show has covered before with Christopher Eccleston’s character. Then again, it is fertile ground. More than that, Moffat has been running the show for three seasons at this point; enough time has passed that he can begin to touch upon and explore the thematic ground carved out by is predecessor.

Into the Dalek expands Clara’s character. One of the best innovations of the Moffat era has been the idea that a normal life is not impossible for a companion. Amy and Rory were able to balance their obligations and responsibilities, at least for a while. Clara can hold down a job and may even have a relationship. “You’re not my boss,” she tells the Doctor. “You’re one of my hobbies.” He isn’t even her only hobby. The show has reached a point where the Doctor is not, to quote Sarah Jane in School Reunion, a companion’s whole life.

While Clara’s development was hampered by the decision to introduce her as a riddle rather than a character during the second half of the previous season, she really shines when paired with the Twelfth Doctor. Into the Dalek does a nice job of explaining why the Doctor needs a companion around. He actively seeks Clara out after encountering the Dalek, because he is incapable of completing this adventure alone. This feels like a much healthier and balanced relationship than some previous dynamics in the TARDIS, even if it has its own issues.

Into the Dalek also carries over a few themes from Deep Breath. Missy makes her second appearance here, and Into the Dalek makes a rather conspicuous comparison between Missy and the Doctor. After all, the Doctor saves Journey Blue from an event that should have led to certain death; this mirrors Missy’s “modus operandi” across the season, as she scoops up consciousnesses from across time and space. The idea of breathing also recurs, with the Doctor advising Clara not to hold her breath while they venture into the Dalek – here we are warned not to breath deeply.

Of course, Into the Dalek is also the second episode directed by Ben Wheatley. Wheatley did a nice job with Deep Breath, even if the material was fairly standard. Into the Dalek is a little more “out there”, allowing the film director to sink his teeth into some impressive battle sequences and some haunting abstract imagery. Most obviously, Into the Dalek positively basks in the sort of militarism associated with the eighties Dalek stories like Resurrection of the Daleks or Revelation of the Daleks, with considerable attention paid to Daleks mowing through extras.

In fact, Into the Dalek goes out of its way to imply that it exists within the same continuity as those eighties Dalek episodes. “He might be a duplicate,” Morgan remarks of the Doctor. He is not describing one of the “human Daleks” featured in Asylum of the Daleks. Instead, he is talking about the type of infiltrators featured in Resurrection of the Daleks. One of the more endearing aspects of Moffat’s tenure is the sense that absolutely every Doctor Who story happened, from comic strips to audio plays to those convoluted and messy eighties Dalek episodes.

For all that the central concepts of Into the Dalek are weird and experimental, Doctor Who hasn’t done a straightforward “sci-fi slaughterhouse” Dalek story like this since The Parting of the Ways, itself an episode that drew rather heavily from the Colin Baker era of the show. Wheatley has great fun with the show’s production value, as the Daleks tear through the wave after wave of expendable human soldiers. It is not particularly novel or deep – and it is nowhere near as scary as Dalek was – but it is fun.

Wheatley also does an excellent job managing the trippier sections of the story, the smaller weirder elements. Into the Dalek has its own interesting eye motif. The Doctor and the team enter the Dalek through the eye stalk. Clara’s shirt is patterned with eyes. The Dalek antibodies look like disembodied Dalek eyes – eyes without a brain to process the imagery. Given that Into the Dalek is fascinated with the Doctor’s perception of the Daleks and ideas of scale or perception, it certainly feels thematically appropriate.

In particular, the scene of the Doctor and his team entering the Dalek through its eye stalk is deliciously trippy and beautiful, lending Doctor Who a surreal air that it hasn’t enjoyed in quite some time. It looks almost as though the characters have wandered into the classic sixties credit sequence, lots of strange lighting effects and stretched imagery. It is bizarre, in a strangely compelling fashion. Into the Dalek might not be consistently brilliant, but it is never less than interesting.

Into the Dalek suffers because it feels a little overly familiar. However, despite this, there is a lot to like. It is decidedly surreal and odd – a unique take on the eponymous monsters. Given that they have been around almost as long as the show itself, that is quite the accomplishment.

You might enjoy our other reviews from Peter Capaldi’s first season of Doctor Who:

- Deep Breath

- Into the Dalek

- Robot of Sherwood

- Listen

- Time Heist

- The Caretaker

- Kill the Moon

- Mummy on the Orient Express

- Flatline

- In the Forest of the Night

- Dark Water/Death in Heaven

Filed under: Television | Tagged: Dalek, daleks, doctor who, into the dalek, peter capaldi, phil ford, stephen moffat |

Actually I’d say the thesis of “The Day of the Doctor” isn’t that the Doctor should not be capable of committing genocide, but that he is quite capable of it, but powerfully prefers not to when given an other option…and that his companions are part of what ensures he seeks those options.

It’s pretty straight-forward logic. The War Doctor thinks he has to commit genocide. He hates it, but is going to do it, and accepts that he’s betraying his own preferred ideals in the process. His future selves all think that he did commit genocide, and are fleeing from that decision: rejecting their former incarnation, twisting themselves into emotional knots over his presumed actions. The story forces them all to review the critical moment of choice–and the future incarnations end up agreeing with the War Doctor: there’s no other choice. Genocide is the only option, for both the Daleks and Gallifrey.

That’s a crucial element of the story–the point at which the Doctor forgives himself, on the terms he has understood to be “real.” For thousands of years and dozens of episodes, through Eccleston, Tennant, and Smith, the Doctor has been in pain and grief and self-loathing over that choice…but when forced to play it all out, a logical step at a time, all the Doctors are in accord, and prepared to carry the burden *even knowing what it will cost them and their own people.* The Doctor is quite capable of genocide.

The gotcha is that it’s the Moment device itself, in the image of Rose Tyler,, and Clara Oswald, who between them find the path out of the maze, and show the Doctor(s) a different way–a loophole.

To me that cold, fierce capacity for Wrath and Smiting has always been part of the Doctor, all the way back to the beginning, but Davies and Moffat have between them each worked to make the theme concrete and central to the character: for both writers it has become one of the primary unifying threads that maintains the Doctor from regeneration to regeneration, He’s a dangerous, powerful creature running from the implications of his own godlike power and nature, and he both plays with humans to hide–and to ensure there’s always a Jimminy Cricket on his shoulder demanding he look, and look, and look again rather than wallowing in his ineffable alien majesty.

In that sense, “Into the Dalek” and Capaldi’s performance, and the underlying script, make a strong restatement of that theme and principle.

Fair point, but I’m not entirely convinced.

The Day of the Doctor is about re-writing history so that the Doctor does not murder millions of children. Moffat has explicitly says as much in interviews. Davies saw the Doctor as a man who could murder millions of children if it kept the universe safe. Moffat sees the Doctor as somebody who has to be better than that.

When the Doctor struggles with his conscience about destroying Gallifrey in The Day of the Doctor, this is presented as a moral failing because there should be a better way, and there is. When the Doctor struggles with his conscience about destroying Earth and the Dalek horde in The Parting of the Ways, this is presented as a highly ambiguous decision that maybe explains why the Ninth Doctor is not long for this world. In The Day of the Doctor, destroying Gallifrey is the wrong thing to do. In The Parting of the Ways, destroying Earth and recreating the end of the Time War is the least wrong thing to do.

Davies treated the Doctor’s name and reputation as “the man who made people better” as something applied to his companions. Rose, Martha and Donna became more than they would otherwise have been through travelling with him. Moffat broadens that out to a mission statements for the character. The Doctor could never comfortably call himself the Doctor while doing terrible things, as demonstrated by the War Doctor and the Eleventh Doctor’s observations in The Beast Below.

This is quite clearly evidenced just looking at the stories. Davies’ Doctor was prone to acts of incredible cruelty and genocide. The Doctor slaughters most of the Slitheen, the Krillitanes, the Daleks (repeatedly), the Cybermen (repeatedly), the Pyroviles and so on. The Tenth Doctor and Donna destroy Pompeii together. Davies’ run ends with the revelation that the Doctor didn’t destroy Gallifrey to stop the Daleks, he did it to destroy the Time Lords.

In contrast, the incidents where the Eleventh Doctor committed genocide are few and far between. The murder of the fish vampires in The Vampires of Venice stand as the exception rather than the rule. Even the Daleks typically live to fight another day. The Eleventh Doctor is a man who lives up to the name “Doctor”, in all its connotations.

While the Eleventh Doctor has his failures and weaknesses – his complete inability to understand Amy and his struggles to a good friend and husband – these are very different from those of his two predecessors. All of the revival Doctor have struggled with the question of what it means to be a good man. The Ninth and Tenth Doctors struggled with the “good” part of that equation. The Eleventh Doctor had a much stronger moral character and often struggled with the “man” part, having difficulty with the intimate and the personal.

All of which is rather longwinded. However, the point is: I would believe that the Ninth or Tenth Doctors would have pushed the cyborg to his death in Deep Breath (the Tenth would even have said “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry” beforehand); I do not for a moment believe that the Eleventh would have, and it would feel majorly regressive if the Twelfth did so. (And, while I may be surprised, I don’t think that he did push the cyborg to his death, at least not under the conditions we saw in the actual episode.)

Also, to be clear, I don’t really prefer one approach over the other, and see the appeal of both. However, I think that Moffat has already done a pretty thorough job outlining his feelings on the matter, and so Into the Dalek feels a bit too much like a retread.

Moffat essentially wrote an “And then I woke up and it was all a bad dream” script. Those are usually horrible, specifically because they undo any moral element of what went before. But Moffat chose very specifically not to use the full capacity of that sort of rewrite. He undid the action while pointedly retaining the underlying truth about the Doctor’s capacity for that action. He left the capacity for evil not only unchanged, but reaffirmed. In terms of future writing, that’s a critical distinction.

In a script of this type that is a big deal, because it’s easier to write it all out. To surgically excise the genocide while actually increasing the level of genocidal capacity and will? That takes some work and some very careful thought. If Moffat worked that hard to accomplish a surgical strike removing the first and an air drop increasing the supply of the second, it seems most likely he did it by intent.

IMO he knew what he wanted to do with Capaldi’s incarnation. I mean, he kind of has to have: he was writing “Day of the Doctor” even as he was setting up for the transition and doing the enormous overview of the past prepping for the 50th Anniversary stuff. When he wrote “Day of the Doctor” he knew he was laying the groundwork for what he wanted to do next very much in light of what had gone before, and “correcting” toward a more classic–and classically dark and intimidating–Doctor.

If you want to go dark with the Doctor; if you want to return to the edge of several of the originals, if you want to really ask hard questions about whether the Doctor is good by human standards, and you want to do it in a kid show, it helps enormously if your character is capable of evil, but does NOT have the destruction of two races on his hands, because actual genocide in the end overwhelms the light, and you’re back to another decade of the Doctor fleeing the unspeakable and unforgivable. Even Smith’s Doctor was, in the end, correctly shown as running away from the Destruction of Gallifrey and the Daleks in the heart of the Time War. Three entire incarnations kept coming back to a blood debt of such scope that all even the Doctor can do is murmur over and over again, “I”m sorry, I’m sorry, I”m so, so sorry,” and hide from himself.

The change leaves Moffat free to set up what, I suspect, will be an arc-long, and even a regeneration-long dialog between The Doctor/Healer, and The Doctor/Warrior. The Doctor we see here, who turns away Journey Blue and who would likely have no place in his Tardis for Danny Pink–the Doctor who identifies himself as a “civilian” who communicates with soldiers through tears, can be forced to realize he is also the soldier who communicates with civilians through tears. He’s allowed to be a soldier, a veteran, scarred, even capable of great evil, and right to be profoundly ambivalent about it–but not a war criminal.

Moffat could not hold that dialog between aspects of the Doctor if he were writing/producing for a character who had killed that horribly, and on that scale. It’s too big. It’s too complete. It’s My Lai and Dresden and Auschwitz and Hiroshima all rolled up into one seething, festering, outsized mess. it’s not just whether the Doctor can be capable of committing genocide, it becomes a question of what to do now that he has.

Moffat needs a Doctor who could have and who would have committed genocide: that dark, painful, scary aspect is necessary and can’t be fake or it all becomes rather twee and precious. But he also needs a Doctor who hasn’t actually done so, or it becomes too horrible, and the lead becomes a Cheney or a Hitler rather than a Danny Pink or a Journey Blue.

Moffat would not be able to write that using only the Davies’ era version of canon and Doctor–but he ALSO could not do that with the Doctor you suggest, who is incapable of that kind of action. It’s easy to oversimplify–to suggest that if Moffat got rid of the Doctor committing genocide, that he’s saying the Doctor should not be capable of committing genocide. But that’s not what he actually wrote and it’s not what he appears to be writing now.

Basically Moffat’s found a very useful way to dial Davies’ bloodbath crux event down one notch, allowing him to tell darker and more nuanced stories than he could have as long as the spatter of Gallifreyan and Dalek blood kept interfering with the dramatic field of vision. But it’s critical that we know–that Moffat wrote–that the Doctor is capable of picking up that axe and chopping away with it. If the Doctor doesn’t actually have the capacity–if it really is not part of his underlying programming–then his moral self-examination is just self-indulgent…Like brooding on your inherent math skills because you can mange 2+2.without ending up with pi.

Moffat, in short, did undo canon and free the Doctor from the weight of genocide. That’s important. But it is exactly as important to note that Moffat did not write out that capacity or intent. If anything tied it even to the regenerations that followed: The Doctor he wrote is quite specifically able to go there, and continues to grapple with that truth.

That’s a reasonable argument. Of course the Doctor has done it, and of course he’s capable of doing it. Davies wasn’t even the first writer to incorporate genocide into the Doctor’s standard operating procedure. It is there since the earliest days of the show. (The Ark in Space is the first example that comes to mind, but I’m fairly sure there are earlier examples.) I don’t doubt that the next showrunner after Moffat could return to that as a storytelling device. After all, the evolution of Doctor Who is not a straight line.

Still, there’s still the fact that Moffat’s second script as showrunner featured the Doctor confronted with a horrible choice where he could not find an outcome with any level of decency for anybody involved, and decided that he if we were to take that horrible action, he could not call himself “the Doctor” any longer. (And, in that case, the companion – as with The Day of the Doctor and in Into the Dalek – was the one to say “hold up, there has to be a better way.” And there was.)

I think it’s reasonable to infer from that there are some things that Moffat believes the Doctor cannot do while still remaining “the Doctor.” Which is to say that Moffat’s undoubtedly believes that the Doctor is capable of doing something like that, but he is not capable of doing that while still calling himself “the Doctor.” If he did, he would have to earn that title back. And that seemed to be a major part of The Day of the Doctor, the idea that the Doctor was able to “fix” a past mistake, given time – to actually heal rather than simply triage.

Yes, the War Doctor was willing to do it, and yes the Ninth and Tenth Doctors believed that they had done it, but The Day of the Doctor changed it so that the biggest stain on the character’s legacy was removed. And while he has to face the reality that he could have done it, there are also all the untouched and unaltered mass-murders from the Davies years that still hang over him. He still killed the Krellitines, the Pyreviles, the citizens of Pompeii.

The erasure of the destruction of Gallifrey from the Doctor’s history was largely symbolic, because it’s impossible to completely erase the character’s history of mass-murder. Instead, it represents a mission statement about how perhaps the show had been too quick to play that “lonely (wrathful) god” card. After all, Moffat reversed a number of creative decisions from the Dvies era, right down to the Doctor’s reputation and renown.

I can’t help but think of The Doctor’s Daughter in this regard, the episode that ends with the Doctor refusing to kill a man in cold blood with a gun – claiming to be be “a man who never would.” Never mind that the Tenth Doctor had committed mass murder before and after that point, and would even use the gun at the climax of The End of Time. That “man who never would” feels like a more aspirational figure for Moffat’s run – something that the show more earnestly strove towards during the Moffat era.

The Eleventh Doctor’s arc seemed to be that of a man who had, but didn’t want to any longer. Of course he was capable of it, just like most people are capable of anything in the right circumstances, and of course he had done it, but the character arc from The Beast Below through to The Day of the Doctor was a man who wanted to make things right. He goes back to visit Amelia at the end of The Angels Take Manhattan; he does right by River Song; he eventually manages to undo the destruction of Gallifrey. Being a good person takes hard work, and I think that the Eleventh Doctor’s character arc was watching him put in that work. (Much like the Ninth Doctor worked hard to become a functioning person capable of trust and love after a horrific trauma. The Tenth Doctor… he didn’t really have a consistent arc, did he?) Seeing it broached here seems like it’s old ground.

I’m a big fan of Moffat, and I love his writing and his baiting and switching, but it feels like he’s already covered this ground. For me, reversing the destruction of Gallifrey was the end of a clear character arc that saw him backing away from certain aspects of the Davies era. You seem to see it as the real starting point. (Or rather: I see the “is the Doctor a good man?” question as being resolved by the move away from the Davies era with “here he genuinely tries to be, instead of just feeling guilty about what he has to do”; you see the “is the Doctor a good man?” question as something that can only really be addressed after the tidying away of the clutter is complete.) I suspect it’s mileage varying.

Just, personally, I think “you would make a good Dalek” is more cutting delivered to a man who thinks he murdered an entire planet full of women and children for “the greater good” than “you are a good Dalek” is applied to a man who just saved a planet full of women and children because he was finally (eight years after the fact in production time, centuries if not millennia in real time) capable of fixing that problem.

(By the way – because I’m always worried about how tone comes across in these responses – you do raise some very interesting and well-thought out points and have given me a lot to digest. I have been meaning to rewatch Day/Time again, and you may have given me cause.)

(grin) No worries. What we’re doing is called “rational discussion” in normal venues. Granted, this is the internet, but I’m inclined to still consider it a rational discussion between two fans of good will.

I’m considering “how I see” Moffat pulling back from Davies’ canon of the Time War…

First, I can agree entirely: I think Moffat feels the Doctor can’t fully remain the Doctor if he really committed the kind of mass genocide of Davies’ reboot. To a dramatist, a genocidal war criminal looking for peace and redemption is a different kettle of fish than a dangerous, random, powerful being capable of genocide and even inclined to that kind of wrath–but who hasn’t committed the act. From the POV of a writer, the two have different natures entirely, in the sense that you have to write them differently, and they mean different things within their fictions.

I myself would say that Davies’ Doctors were always in some sense a statement that what we’d believed the Doctor to be before, and what the Doctor himself wished and wanted and dreamed he could be again was, at heart, a lie. The Emperor had no clothes, the little man behind the curtain was really a rather horrifying monster but NOT “Oz the Great and Terrible.” The Doctor was, ultimately, always a whited sepulchre, no matter how he himself tried to escape that. Every time anyone tried to write Davies’ canon Doctor as the shining beacon of hope, the character himself whispered darkly, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m so very, very sorry,” and ran off to something a little safer.

As I said, it’s too big. It’s got the gravitational pull of a black hole. It warps the character by declaring that everything we believed about the Doctor in pre-reboot days was really a lie. We and the Doctor could never properly recover from his one act out outstanding epic murder, and the Doctor could never really heal from it without becoming even MORE amorally non-Doctorish.

If he was to be good, and “our Doctor,” then the subject could never come up without the Doctor being shown as never forgiving himself. If he forgave himself, he was not “our Doctor.” But if he did not forgive himself, then we and his companions had to–over and over and over again. Dramatically it’s a trap you can never get out of, and one that Moffat seems to have willingly explored–and decided to come away from.

By coming away he is free to ask the same questions and get new answers.

Ok, this is a guess, but one of the things I really expect to see in the next two seasons is a two-part motion–the first has the Doctor brought to the point where Danny Pink, Journey Blue, or another soldier becomes the Doctor’s new companion. Marking the emotional road the Doctor has to walk to make that possible is a great story focus, and one that’s more real *because* he and Clara both know his darkness is not fake, and is not resolved. He has to *forgive* himself for being capable of functioning as a killer–by direct action, and by indirect collateral damage. He’s going to be forced to look at the lives he spends even while saving lives–Half-face Man and Gretchen are being saved up for exactly that kind of emotional trial, that kind of exploration.

Once a “Danny” or a “Journey” can be brought aboard as a companion, though, Moffat can tell still another kind of story: what two healing veterans can do and say for each other and to the universe.

Those stories would be crushed beneath the weight of the destruction of Gallifrey and the Daleks. It’s too huge. Giving your character something that vast and hideous means that it becomes almost impossible to tell the smaller, more intimate, and far more real stories of a lesser guilt.

So, yes, I think I am saying that Moffat’s just starting to explore these themes dramatically–in one sense. By freeing himself from the too-large burden of High Fantasy Dark Lord Intergallactic Genocide, he’s cut himself some room to tell more nuanced, intimate stories. He can ask different questions about the use and abuse of power, about the trustworthyness of a Chaotic Good Trickster.

Moffat seems to feel he/they played out pretty much all you could do with Dark Doctor questions *given the axiomatic truth of a genocidal War Doctor.* He seems to have concluded that the answers you got, no matter how you asked the questions, were ultimately in conflict with the Doctor being a good man, rather than a bad man struggling with his guilt. Most of all he seems to have concluded that the kind of moral question and answer stories and development arcs he wanted to explore next were impossible if he kept the actual genocide, which gets in the way of too much and exerts too powerful and too melodramatic, and hyperbolic a pull.

So, yeah: I do think this is a new cycle, but I also think it’s new so that Moffat can ask old questions and get new answers that were impossible under Davies’ canon. Moffat needed a Doctor who’s dark and deadly enough for the moral questions to be very real and biting. He needs a Doctor who really is a good Dalek in some ways. But he needs the Doctor not to have done something so completely terrible and mythic and huge that it dominates everything.

Does that make sense to you?

It does indeed.

Speaking of Soldier Blue and Danny Pink, I can’t help but wonder if the man we know as Danny Pink was Soldier Blue’s brother. The face was hidden from us during the teaser, and we know that somebody other than the Doctor has been snatching people away at the moment of their death – much like the Doctor did in the teaser to Into the Dalek. So I’m wondering if Missy may be re-depositing them throughout history. Given that Deep breath drew attention to the fact that the Twelfth Doctor’s face was familiar, perhaps there is some sort of cosmic redistribution going on. The Blue/Pink juxtaposition would work in that light.

It would be the ultimate twist on Moffat’s “everybody lives!”

Nevertheless, I like Danny Pink, and can’t wait to see him join the crew.

Ironically, I liked this episode BECAUSE it seemed to go a long way towards undoing what had been established in “The Day of the Doctor.” I’d been more of a Davies than Moffat fan and always thought the lonely god concept to be the more interesting version of the Doctor. So far I’m liking the 12th Doctor as a sort of corrective to the previous era.

It only seems natural that if a brilliant alien could travel through space and time on a whim that he would start to view himself as a god. After all, what does the life of one person at one time matter in the span of a trillion years? If one has such power over life and death, doesn’t it become easier to rationalize genocide as in some cases for the greater good? The beauty of the Davies era Doctor was that he grappled with that question and tried to find value in even ordinary individuals.

The 11th too often completely avoided those questions. He never has to make tough choices or feels the temptation of using his powers “for the greater good.” His caring about children who cry doesn’t mean as much if he’s always wholesome and good, if he can escape tough choices. Staying on Tranzelore to save the town, fighting off fleets of enemies, AND getting a regeneration, AND not having committed genocide means that the 11th Doctor never really had to sacrifice anything in the end. That’s one of the reasons at the end of the day I always thought his character felt flat and uninteresting.

It’s a fair point, but I think that Davies era really mined that particular theme so thoroughly that it was nice to get away from it. The same way that it might be nice to get away from “timey wimey” for a while when Moffat leaves. It doesn’t mean I don’t like those ideas, but I do think that they are best left to the eras of the show which suited them best, or allowed to lie fallow for a while