This October/November, we’re taking a trip back in time to review the eighth season of The X-Files and the first (and only) season of The Lone Gunmen.

Sweeps have arrived. And so has David Duchovny.

David Duchovny appeared in three of the four episodes of The X-Files broadcast in February 2001. (The fourth, Medusa, is very much the “blockbuster” episode of this stretch of the season, with a large budget and impressive scale.) This was very much a conscious choice on the part of the production team. Although Duchovny’s shooting schedule meant that the episodes were filmed across the season, the show made a choice to broadcast them all as part the February Sweeps.

Indeed, even the order of the episodes in question has been jumbled around. The Gift is the third broadcast episode of the eighth season to feature an appearance by David Duchovny; it was filmed before Badlaa, but broadcast after it so as to open the Sweeps season. However, Per Manum would be the fourth broadcast episode of the eighth season to feature an appearance by David Duchovny; not only was it filmed before The Gift, it was actually filmed between Via Negativa and Surekill.

There is a sense, looking at the differences between the production and broadcast orders of the eighth season, that the production team were well aware of just how big a deal the return of David Duchovny would be. In fact, the decision to broadcast The Gift before Per Manum seems like a very canny attempt to tease those viewers excited about the return of Mulder. The character is much more prominent in Per Manum, so it feels like the decision to air his smaller supporting role in The Gift earlier is an effort in building suspense and excitement.

The Gift doesn’t offer much in the way of advancement for the season’s on-going story arcs. Although the teaser is smart enough to build to the reveal of David Duchovny, the character only appears in quick flashes throughout the episode. Mulder has less than half-a-dozen lines over the course of the show’s forty-five minutes. He does not directly encounter (or engage with) Doggett or Scully, only appearing for a brief moment as a vision in the basement at the end of the episode. Fans eagerly anticipating Mulder’s return would undoubtedly be frustrated.

However, there is something almost endearing in the show’s playful teasing of its fanbase. It feels almost like the show getting comfortable with itself once again. Indeed, the structure of the episode – paralleling Mulder’s investigation with that of Doggett rather than intersecting them – seems to suggest that perhaps the show might be in good hands without the need to have Mulder literally validate his successor.

David Duchovny’s pseudo-departure had generated a lot of attention and press in the run-up to the debut of the eighth season, which served to make the opening of a “Mulder-less” season something of an event itself. There was a curiosity around the broadcast of Within and Without, with many viewers wondering how exactly the production team would pull it off. Mulder was such an essential part of the show’s identity that the idea of “The X-Files without Mulder” aroused a great deal of fascination.

Three months later, the novelty had faded. At this point in the season, the presence of David Duchovny would serve to distinguish any episode as a special episode. His appearance in The Gift is enough to render the episode an “event”, in the same way that the mythology episodes from the first second through sixth seasons were an event. It made sense to concentrate David Duchovny’s appearances as Mulder during the Sweeps period. As traumatic as his departure had been, it immediately offered the show a great deal of hype.

Still, with all of those expectations and pressures, it is perhaps surprising that The Gift feels like such a traditional episode of The X-Files. Perhaps as part of a concentrated effort to reassert its own identity, the eighth season of The X-Files had adopted a “back to basics” aesthetic, harking back towards the vintage years of the show. The eighth season eschewed comedy episodes and embraced darkness, trying to recapture the essence of the Vancouver era. It also attempted to engage with some of the classic themes of the show.

Roadrunners was very much a classic “small town with a dark secret” story, harking back to Our Town or Home. Badlaa marked a return to the “creepy foreigner” school of horror that had led to episodes like Excelsis Dei, Teso Dos Bichos and El Mundo Gira. If it weren’t for the lack of David Duchovny, it seems like the traditionalist fans who had decried the era of so-called “X-Files Lite” would have welcomed a return to classic X-Files values. Frank Spotnitz’s script for The Gift plays on a number of classic X-Files tropes.

Most obviously, The Gift is the story of a small town with a dark secret. In particular, it turns out that the residents of Squamash have been exploiting an innocent creature for their own convenience. Spotnitz seems to like these sorts of stories; both Our Town and Three Percenters featured predatory cannibalistic small towns. It is a particularly cynical depiction of these sorts of communities, but one that could also be expanded out to a criticism of society on a larger scale.

In many respects, the Native American “soul eater” at the heart of The Gift is just another example of an innocent being made to suffer for the happiness of the larger community. It is a potent metaphor for how societies and cultures work, with the needs of the individual often subsumed into the needs of the larger group. It recurs time and again throughout literature, whether through the ritual sacrifice in Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery or the suffering child in Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.

Indeed, the central thought experiment was suggested in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, in which Ivan wonders just what price people would be willing to accept for comfort and security:

Imagine that you are creating a fabric of human destiny with the object of making men happy in the end, giving them peace and rest at last, but that it was essential and inevitable to torture to death only one tiny creature — that baby beating its breast with its fist, for instance — and to found that edifice on its unavenged tears, would you consent to be the architect on those conditions?

It is a fascinating (and terrifying) thought-experiment. It is also a theme quite close to the heart of The X-Files. After all, the conversation between the Cigarette-Smoking Man and Jeremiah Smith in Talitha Cumi draws upon similar themes.

One of the central recurring anxieties of the mythology is the question of just what atrocities underpin the so-called “unipolar moment.” Having emerged from the Second World War and the Cold War as the most powerful and successful nation in the world, The X-Files repeatedly asks what kinds of sacrifices were necessary to secure that prosperity and security. From the relative comfort of the nineties, The X-Files explored the compromises that had been made by those in authority; it even wondered about the public’s passive complicity.

The mythology tied a lot of those compromises back to the end of the Second World War, with Paper Clip and Nisei exploring the deals that had been made with Axis war criminals to further American scientific progress. Illegal human experimentation was a recurring motif on the show, drawing from accounts of the Tuskagee Syphilis Experiments and MK-ULTRA; not to mention illegal radiation trials against prisoners and civilians. The comfort enjoyed by the United States was built upon a lot of suffering.

However, the compromises went back even further than that. Episodes like Darkness Falls suggested that the European settlers were ultimately still aliens in the United States. Anasazi tied the mythology into the genocide of the Native Americans by the European settlers. The show suggested that the European settlers were about to find themselves victim of a similar colonising force. In fact, The X-Files: Fight the Future suggested that humanity were not the original inhabitants of Earth.

The Gift returns to these themes for what feels like the first time in quite a while. The three-parter bridging the sixth and seventh seasons (Biogenesis, The Sixth Extinction, The Sixth Extinction II: Amor Fati) had returned to indigenous mysticism, but the show’s engagement with issues of colonisation had largely faded into the background with the collapse of the mythology in Two Fathers and One Son. When the show moved to Los Angeles, it seemed less likely to engage with big historical issues. (Contemporary class issues became more pressing.)

Indeed, many of these issues had been shifted over to Harsh Realm. The series featured General Omar Santiago setting out upon his own “manifest destiny”, trying to bend the continent to his whim. Within that framework, Chris Carter’s virtual reality war story could touch on the shaping of the United States itself, with Reunion exploring the role of slavery and Cincinnati touching on the exploitation of indigenous people by the settlers. Perhaps it made sense for The X-Files to drift away from these themes to allow Harsh Realm its space.

Nevertheless, The Gift returns to these ideas. The episode is saturated with images and concepts that evoke some of the more unpleasant aspects of the American frontier myth. The treatment of the soul-eater is couched in imagery associated with the slave trade, as the community tries desperately to hunt the creature down when it escapes. The methods employed – trained hunting dogs, nets and cages – are all consciously chosen to evoke slavery. (In particular, the image of slavery as it exists in the popular mind, shaped by Roots.)

When Doggett confronts the residents of Squamash about their treatment of the soul-eater, the conversations is couched in the language of slavery. The town’s inhabitants are able to justify their exploitation of the creature by insisting that it is an object rather than a person; denied personhood and agency, abuse is rendered as mere use. “You can’t take it, Agent Doggett,” Sheriff Frey insists. “It belongs to us.” He is property. Doggett responds by asserting the creature’s humanity. “This is a man. He doesn’t belong to anybody.”

(Doggett confronting the townspeople is an important character touch. The flashbacks indicate that Mulder realises that the creature is suffering at the last minute, just as he is about to exploit its gift for its own end. Although he eventually makes the leap, his is blinded by its supernatural powers. This is consistent with Mulder’s behaviour towards Clyde Bruckman in Clyde Bruckman’s Final Repose and his difficult seeing Jennie as a person in Je Souhaite. Doggett doesn’t have that baggage, so he can recognise a creature in pain first and foremost.)

However, the soul eater is also explicitly identified as Native American in origin. Byers suggests that the symbol used to summon the creature is associated with “North American shaman.” There is a sense that the soul eater is anchored in Native American beliefs and spirituality, another example of the show’s long-standing fascination with Native American mysticism and iconography that can be traced back to Shapes during the first season and which reached its zenith during The Blessing Way.

However, there a number of very important and very clever differences between the use of Native American iconography in The Gift. It seems like Frank Spotnitz’s script is offering something of a commentary on how the show has approached such portrayals in the past, and attempting to use the transitions and growing pains of the eighth season to clearly delineate between what came before and what came after. The eighth season of The X-Files plays as a nice final season for Mulder and Scully, but it also plays as a possible new beginning for the show.

In this respect, it is interesting that Frank Spotnitz established himself as the go-to Doggett writer during the early eighth season. Over the course of the season Spotnitz is credited on eight of the season’s twenty-one episodes; Carter is credited on nine. Notably, Spotnitz is responsible for the two “Scully lite” episode in the “Mulder-less” stretch of the season, Via Negativa and The Gift. This makes Spotnitz the staff’s de facto Doggett writer. No wonder Spotnitx described the season as “one of [his] best years, if not the best year, [he’s] had on The X-Files.”

All of this was occurring while Spotnitz was also overseeing production of The Lone Gunmen with Vince Gilligan and John Shiban. Fox had officially greenlit a spin-off from The X-Files that was in production in parallel with the second half of the eighth season. Carter had largely delegated the day-to-day running of that show to his three most trusted writers. This had the effect of limiting the contributions that Gilligan and Shiban could make to the eighth season; Spotnitz managed a simply phenomenal workload.

In fact, The Gift was in production while the team were working on The Lone Gunmen. The appearance of the Lone Gunmen in the episode was actually filmed by the production team working on The Lone Gunmen. Spotnitz recalls, “The scene with the Lone Gunmen talking via Internet videophone to Doggett and Skinner was actually shot on the set of the spinoff series, with Bryan Spicer directing.” While Millennium had to wait until it had been cancelled before crossing over with The X-Files, The Lone Gunmen was crossing over before a single episode aired.

There is some speculation that Spotnitz was very much heir apparent to the showrunner job on The X-Files if Chris Carter ever decided to take a less hands-on approach to the running of the show. After all, Carter had suggested that his attachment to The X-Files was largely rooted in a promise made to Gillian Anderson and David Duchovny, so he might be willing to step back if the show continued without so strong a focus on Mulder and Scully. Having helped shape the mythology and write Fight the Future, Spotnitz was the logical choice.

Chris Knowles, author of The Complete X-Files, has pointed out that there was a possibility that Spotnitz could have taken over following the eighth season. Tom Kessenich contended that there was some ambiguity around the possibility of Carter returning for the ninth season even as it entered production:

Planning for the ninth season began in June with Carter absent for the first time since he created the series in 1993. He has yet to reach a deal with Fox to return for the ninth season and there is speculation he will not return or serve only as a “consultant,” with Spotnitz assuming the lead role for the show’s creative decisions along with co-executive producers Vince Gilligan and John Shiban.

Carter declined to be interviewed for this story, but Spotnitz said it has been odd going to work without the show’s creative driving force around.

“Obviously, we hope he comes back because it’s his show, it’s his vision that we’ve all been serving for all these years and he’s an enormously talented writer and producer,” said Spotnitz, who has been in charge of the series with Carter gone. “If he doesn’t, it’s not like we don’t know where all the files are.”

There is a sense that the eighth season works as both the final season of the traditional X-Files model with Mulder and Scully, but also as a possible first season for a new (and radically different) iteration of the show.

Broadcast in the middle of the season, The Gift seems to parallel these two versions of the show. Even structurally, the decision to parallel (rather than overlap) Mulder and Doggett’s investigations into Squamash serves to delineate the end of Mulder’s quest with the start of Doggett’s. It also provides an opportunity for reflection and contemplation about the application of certain themes and tropes within the series as a whole. The Gift suggests a discomfort with how The X-Files has dealt with Native American culture in the past.

The Gift is fundamentally about the exploitation of Native American culture by a white town. It is interesting how the script seems to consciously avoid the trappings employed in scripts like Anasazi or The Blessing Way (or even Biogenesis and The Sixth Extinction). There are no wise Native American characters bestowing wisdom or prophecy, no long-winded monologues about symbols or omens. The Gift is quite literal in its application of Native American culture, with a preference for blunt exposition over evocative lyricism.

Appropriation of Native American culture became a hot button topic during the nineties, as various New Age movements frequently employed (and attempted to monetise) Native American spiritual beliefs for their own advantage. In Spring 1993, the Red Road Collective observed:

We must challenge those who are not our proper hereditary elders who act out of greed and self interest. These individuals hurt and insult our precious elders by impersonating them. We will no longer allow them to disrespect and manipulate our Native people with twisted, racist expectations of our obligation to sacrifice the needs of our communities for their welfare. They have perverted our ceremonies to meet their insatiable need to “feel good” about themselves. They have promoted their offensive psycho-babble version of our rituals, used what we hold most sacred for their profit and amusement. In doing this they have robbed our children of their birth-rights and threatened our survival. We cannot allow European immigrants to take away our birthrite. If we allow them to take our spirituality from us, they will exploit it. They have shown us, over and over again, that their only intention towards this earth is exploitation. Anything we share with them, they will market for profit.

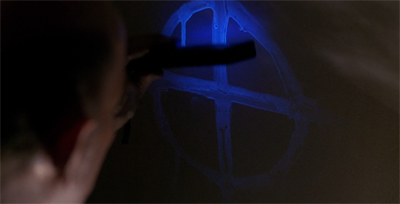

The medicine wheel – the symbol bound to the soul eater in The Gift – was one such bone of contention. As recently as 2011, the Native Student Alliance publicly opposed a medicine wheel ceremony organised in Washington State as an example of such cultural appropriation.

Although there were undoubtedly charlatans hoping to make a quick buck off the appropriation of Native American culture, there were also well-meaning and well-intentioned people who would absent-mindedly contribute to that culture of exploitation. As quoted by Ward Churchill in A Little Matter of Genocide, Pam Colorado explains why even those well-intentioned appropriations are discomforting and offensive:

The process is ultimately intended to supplant Indians, even in areas of their own customs and spirituality. In the end, non-Indians will have complete power to define what is and is not Indian, even for Indians. We are talking here about an absolute ideological/conceptual subordination of Indian people in addition to total physical subordination they already experience. When this happens, the last vestiges of real Indian society and Indian rights will disappear. Non-Indians will then “own” our heritage and ideas as thoroughly as they now claim to own our land and resources.

The production team had no desire to cause offense with episodes like Shapes or A Single Blade of Grass, but there are undoubtedly some uncomfortable elements to their portrayal of Native American culture. The Gift could be read as an acknowledgement of – and perhaps a commentary upon – that exploitation and appropriation in earlier seasons.

This is not the only way that The Gift feels like an attempt to acknowledge the past while also pointing towards the future. Although the episode makes very limited use of Duchovny, the structure is very clever. As with Via Negativa, Doggett is positioned in relation to Mulder’s absence. Most obviously, he is still attempting to solve Mulder’s disappearance, but The Gift finds the character effectively retracing Mulder’s footsteps. Doggett is trapped within a case that Mulder has already (at least in theory) resolved.

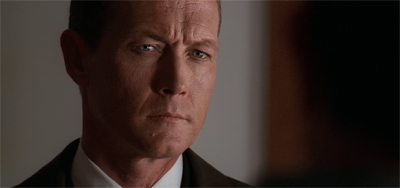

One of the more interesting (and intelligent) aspects of the eighth season is the way that it refuses to downplay Mulder’s absence or Doggett’s status. The show is very careful to assure viewers that Doggett is not an attempt to replace Mulder, and that the show will not be attempting to get back to “business as usual” without David Duchovny by slotting Robert Patrick into his role. Mulder’s absence informs and shapes the eighth season, with the production team acknowledging the awkward position in which Doggett finds himself.

Indeed, some of the best character work in the eighth season occurs while Doggett and Scully are separated from one another. While Mulder and Scully were a duo that brought out the best in each other, the eighth season seems to suggest that Doggett and Scully are more interesting as individual characters than as a collective team. Scully is most interesting when venturing out on her own literally (Without, Patience) or emotionally (Badlaa) and Doggett is best defined while separated from Scully (Via Negativa, Medusa).

While the parts of the seventh season that Mulder and Scully spent apart were among the most frustrating (Chimera, Brand X), the parts of the eighth season that treat Doggett and Scully as a unified team are the least satisfying (Surekill, Salvage). With that in mind, allowing Doggett to essentially embark upon his own person X-files without Scully in Via Negativa and The Gift allows the character room to grow and develop. It is as important for Doggett to define himself against Mulder (or Mulder’s absence) as against Scully.

Of course, the decision to exclude Scully from Via Negativa and The Gift was not purely creative. According to The Complete X-Files, Gillian Anderson was taking time off to spend time with her daughter:

“I had a very strict schedule with my daughter. She was in school up in Canada, and I was determined that they respect that I would work for three weeks and then have two or three weeks off to go and be with her. So they agreed to that, and that was important to me. I’d never had that before on the show.“

Regardless of the reasons for building those episodes around Doggett with a minimum amount of Scully, they do allow for a very clear delineation between the show before and after Requiem. Gillian Anderson provides a sense of continuity; her absence emphasises the divide.

On a basic level, The Gift is about demonstrating that Doggett can handle an X-file. Over the course of the episode, Doggett wanders into a strange situation and manages to solve it on his own terms. In that respect, it feels like an organic continuation of Frank Spotnitz’s work on Via Negativa. In Via Negativa, Doggett found himself trapped within a collapsing X-Files narrative, a strange world of dream logic that runs counter to everything he knows. Doggett seemed worried that his inability to accept that world might kill the show.

The Gift suggests that Doggett has come a long way since his inability to accept the logical end point of an X-Files narrative led to nightmares of him murdering Scully in her sleep. Indeed, The Gift even confirms that Doggett is an X-Files protagonist by putting him through the “death and rebirth” arc afforded to all of the major characters. Scully was abducted in Ascension and returned in One Breath. Skinner had his own near-death experience in Piper Maru and Apocrypha. Mulder went through his first in Anasazi and The Blessing Way.

Of course, the entire eighth season could be seen as an extended death and rebirth for Mulder, and for the entire show around him. The recurring use of the medicine wheel in The Gift alludes to this, both in its invocation of the show’s logo and in its deeper symbolism. As Charlton D. McIlwain explains in When Death Goes Pop:

Later depictions of the symbol resemble the more traditional medicine wheel, yet the first time we see it, the picture is identical to The X-Files program symbol. … The precise usage and even some of the symbolism of the wheel are mired in controversy; nevertheless, most scholars agree on some of its essential representations – all of which focus on the idea of synthesis and wholeness, including concepts of renewal and rebirth, the union of nature in calling together the four winds and the approach and passing of the seasons and planetary orbits.

In a way, The X-Files is going through its own death and rebirth not too dissimilar from that experienced by the residents of Squamash. Given some of the difficulties facing the production team, often playing out in a high-profile manner, the process was almost as gory as that depicted within the episode; the show was being broken down and reconstructed in an often painful manner.

However, as much as The Gift is focused on the rebirth of John Doggett (and the show around it) some of the eighth season’s darker death impulses seem to ripple beneath the surface. As much as the eighth season was both a final season and a first season, there was also a recurring sense that it might just best to let The X-Files die. “Everything dies,” promised the introductory text to Herrenvolk, the point at which it became clear Chris Carter’s “five seasons and a bunch of movies” plan would not be happening. Four years later, maybe it was time.

If Doggett represents the optimistic future of The X-Files, reborn and renewed, then Mulder comes to embody the death impulses of the show. Mulder’s “undiagnosed brain illness” proved to be a massive red herring, but it does serve a thematic purpose here. Offered the chance to be reborn, Mulder declines. He accepts the inevitability of his death. More than that, the script contrasts how Mulder and Doggett try to help the soul eater. Mulder wants to let it die in peace; Doggett wants to let it live free.

Frank Spotnitz has confessed that he struggled to conceive of The X-Files without Mulder. While admitting to a fondness for Doggett, he has admitted that if he could change anything about the show’s nine season run he would have not have wanted the show to continue without Mulder:

I loved Robert Patrick, but if there was anything I could change, I would still would’ve loved for him to be in the show, but without Mulder leaving the show. And I say that not as a criticism in any way of David. I completely understand why, after seven years of killing himself, he was tired and didn’t want to keep doing it.

It is an entirely understandable sentiment. A lot of fans watching the show felt the same way. It makes sense that the production team wrestled with those same anxieties. As much as the eighth season wanted to find a sustainable way for the show to continue, it also felt like the show wanted to let go.

This creates a compelling tension within The Gift, with the soul eater itself serving as something of a metaphor for The X-Files itself. Is Mulder right to want it to die? Is Doggett right to want it to live? As with Via Negativa, there’s an intriguing ambiguity there; the creature does die at the end, but it dies in the act of giving life to Doggett. It takes the death that was meant for Doggett upon itself. Does this represent Doggett breaking free of the expectations and pressures of the previous seven years?

The episode alludes repeatedly to the idea that the soul eater is itself a stand-in for The X-Files, an institution that had survived a phenomenally long time in the context of nineties prime-time television. “The things you’re asking about,” the local woman remarks to Doggett, “they’ve been this way for hundreds of years. You can’t change them.” In many ways, this is the larger goal of the eighth season, to find a way to change a system that has worked quite well (creatively and commercially) for seven full years.

One of the more interesting aspects of the eighth and ninth seasons is the sense that the production team were facing opposition from the same fanbase that had helped to turn the show into a hit. A lot of the success of The X-Files was built upon an energetic and evangelical on-line fanbase, The show was engaged with a more dynamic (and even two-sided) relationship with those fans than many of its contemporaries. However, after the move to Los Angeles, it seemed like the relationship between the show and its fans became a lot more taut.

Both “shippers” and “normos” grew impatient with the show’s refusal to commit to one set of fans for fear of upsetting the other. When the production team opened the sixth season by morphing into a weird paranormal romantic comedy, fandom branded it “X-Files Lite” and practically rebelled. The departure of David Duchovny caused another schism, with some fans less than thrilled at the idea that somebody might try to offer them a television show branded The X-Files without Mulder at its centre.

There is a sense that the protection team could occasionally feel a little frustrated with this somewhat possessive (and occasionally reactionary) side of fandom. This tension played out in a number of ways, perhaps most notably in a number of creative decisions during the ninth season – in particular through the somewhat mean-spirited use of Agent Layla Harrison in Scary Monsters. There is perhaps a faint trace of that to be found in The Gift, as the mysterious woman describes the relationship between the soul eater and the townspeople.

“People hate it because they need it,” she tells Doggett. “It looks the way it does because of their sickness.” This feels like a commentary on the paradoxical relationship that had somehow led to the show’s most passionate fans becoming its most voracious critics. These were the people who kept The X-Files alive, but who seemed to resent what it had evolved into in order to stay alive. After all, the most logical course of action for those who hated the show would be to stop watching; to let Requiem serve as the end of their journey.

Indeed, The Gift almost sympathetic to David Duchovny’s decision to leave The X-Files. Frank Spotnitz’s script seems to acknowledge that Duchovny’s absence almost killed the show, but seems to suggest that it might have been a mercy killing. After all, the eighth season was only greenlit at the last-minute, when Duchovny signed a contract to appear in eleven episodes of the season only three days before Requiem aired. If Duchovny had not reached that settlement with Fox, it seems entirely possible that The X-Files would have died then and there.

The Gift suggests that there was no malice to this decision, that it might even have been merciful. Discussing Mulder’s encounter with the soul eater, the mysterious woman explains, “He couldn’t bear to add to its pain.” After all, Duchovny deciding to sign on for another season would just keep the show in a state of arrested development. Doggett expands upon the idea, suggesting, “So he came back here that night to take its pain away.” In a way, Duchovny’s reluctance to sign on for another season might have allowed the show a dignified death.

As with Via Negativa, there is a certain ambivalence to The Gift. It seems like The X-Files is caught between wanting to press ahead into a bold new future and yearning for the release and freedom of cancellation. There is an energy to the eighth season that was sorely lacking during most of the seventh season, but it is an energy caught between the possibilities lying ahead and the comfort of resolution. The structure of The Gift allows the show to play out both narratives in parallel, to acknowledge both the show’s death and its rebirth.

In the end, it seems like the two are inexorably linked. Mulder accepts his pseudo-death, the creature dies, but Doggett lives. Naked and covered with viscera, The Gift is rather explicit in its birth imagery. One of the more compelling aspects of the eighth season as a whole is the fact that so many of the core story beats feel mythic and epic in tone, providing a clear structure and arc to the season’s storytelling. Even when the individual stories aren’t great, there is a sense of mythic scale to everything.

Of course, some of those mythic inspirations are a little obvious. Mulder’s death and rebirth in This is Not Happening and DeadAlive represents at least the fourth time that the show has put Mulder through a Jesus Christ crucifixion and resurrection arc. Although it represents the first time that the show has offered its own take on the nativity, Essence and Existence can seem similarly corny. However, these familiar and epic story beats work well juxtaposed against the more intimate storytelling of the season around them.

The show has toyed with the idea of imposing these mythic story structures before. In particular, David Duchovny was very interested in taking Mulder through a character arc inspired by Joseph Campbell’s monomyth; there are elements of that to be seen in Colony, Anasazi and Talitha Cumi. However, the show was never entirely consistent in this approach. There is no stretch of The X-Files where Mulder is plotted through a Joseph Campbell arc as consistent and structured as the one that Frank Black navigates in the second season of Millennium.

Even the eighth season of The X-Files doesn’t have that clear a structure or framework. After all, Mulder’s undiagnosed brain illness turns out to be nothing more than a red herring with some small thematic resonance. Still, there is a sense that the production team are consciously drawing on established mythical frameworks in their approach to storytelling. In particular, the show seems to position John Doggett on a quest from Arthurian legend; the character is essentially on his own grail quest.

To be fair, The X-Files has employed no shortage of grail imagery before. Firewalker was set at Mount Avalon, for example. This is a recurring motif in the mythology. Characters in stories like Anasazi, Gethsemane and En Ami frequently argue that some piece of information is the grail; the obvious implication is that Mulder and Scully were on their own grail quest. The show has never pushed the imagery too far, but it does provide a mythic resonance to Mulder’s quest.

However, the eighth season suggests that Doggett might be on his own grail quest during the hunt for Mulder. Indeed, it could be argued that the eighth season is structured as something resembling the story of the Fisher King, casting Mulder in the role of the Fisher King and Doggett in the role of Percival (or Galahad). The basic structure of the Fisher King myth finds a wounded king tasked with protecting the Holy Grail. The Fisher King’s wounds become reflected in the kingdom around him, as he waits for a virtuous knight to arrive and lift that curse.

One a very basic level, this template would seem to apply to the eighth season. Mulder is very much the Fisher King; he was one of the two leads character on The X-Files, and his departure cast a long shadow over the series. He is the one who keeps “the grail” – the show’s quest for truth. Quite a few fans and journalists speculated on whether The X-Files could survive without Mulder, or perhaps transform into a wasteland. Even within the world of the show, the landscape seemed to change; the cases became a lot darker and more ominous in Mulder’s absence.

The myth of the Fisher King also ties into issues of fertility and virility that relate to the eighth season as a whole. In the larger structure of the eighth season, it seems that Mulder’s absence is defined primarily in terms of Scully’s pregnancy. One of the bigger mysteries of the eighth season is the identity of the baby’s father. In most variations of the Fisher King myth, the king is wounded in the groin or upper legs; the symbolic wound inflicted upon his kingdom is to render the land barren. In the eighth season, Mulder’s disappearance is tied into issues of fertility.

There are a number of obvious parallels to be found in various versions of the Fisher King myth as it was reinterpretted. In Joseph d’Arimathie, it is suggested that the Fisher King comes to hold the Holy Grail because of his family connections as the brother-in-law of Joseph of Arimathea; this parallels the connections repeatedly made between Mulder’s own family and the mythology. Although the nature of “the healing question” that is necessary for Percival to heal the Fisher King changes between versions, emphasis is put on knowledge as the key to the quest.

The Gift plays up these mythic similarities. Doggett finds himself pursuing the wounded Mulder, attempting to solve the mystery of his disappearance. The X-Files has always treated “the truth” as synonymous with “the grail”, and that is certainly true in this episode. However, the soul eater itself takes on the most mythic quality of the Holy Grail; it can heal any wound. Over the course of The Gift, Doggett finds a way to complete Mulder’s work on the case. In doing so, he allows Mulder to return to the basement office (his kingdom, perhaps) – even if only in astral form.

Through The Gift, Doggett comes to understand the way that Mulder works. As with Percival’s need to ask “the healing question”, it seems that reconciliation begins with a curiosity and a willingness to comprehend. Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival goes further in its interpretation of “the healing question.” It suggests that Percival’s understanding of the Fisher King must be based on empathy rather than cold knowledge. That the key to Percival’s quest is in recognising the suffering of the Fisher King and acknowledging it.

The Gift nods towards this in two different ways. Over the course of the episode, Doggett comes to understand how Mulder works; he dispels the idea that Mulder killed a man in cold blood and disappeared to avoid the consequences. More than that, though, Doggett proves himself a worthy successor to Mulder when he realises the pain and suffering inflicted upon the soul eater and takes it upon himself to try to resolve the situation. These parallels lend a nice mythic quality to the larger eighth season arc.

That said, the episode also seems to allude to other later (and more cynical) interpretations of the Fisher King myth. Naked, lit by torchlight, and covered in clay, the reborn John Doggett looks almost like Captain Benjamin L. Willard at the end of Apocalypse Now. Both men have been changed by their quest, having ventured from the relative safety and security of the normal world into an almost magical realm that is all the more surreal and unknowable. Apocalypse Now drew from its own interpretation of the grail myth.

In Peter Cowie’s Coppola, director Francis Ford Coppola talked about how he structured the story around the classic Arthurian legend of the Fisher King:

I was really on the spot. I had no ending. … So with the help of Dennis Jakob I decided that the ending could be the classic myth of the murderer who goes up the river, kills the king, and then himself becomes the king – it’s the Fisher King, from The Golden Bough. Somehow it’s the grand-daddy of all myths.

It is, perhaps, a rather cynical take on the myth of the Fisher King; it is a version of the story where Percival does not heal the Fisher King, but ultimately kills him.

Again, there is a sense of ambivalence and impunity running through The Gift. Perhaps John Doggett is not the gallant knight who has arrived to restore peace and prosperity to the kingdom; perhaps John Doggett has arrived to displace the Fisher King once and for all, destroying the kingdom in the process. It feels like a lot of the same anxieties that ran through Via Negativa, as if The X-Files itself is not entirely sure about whether the show can survive this particular transition.

After all, Francis Ford Coppola is not the only person to put a cynical or negative spin on the story of the Fisher King. T.S. Eliot had used the grail myth and the Fisher King as a loose frame-work for The Waste Land, his critical exploration of early twentieth-century British cultural. The poem repeatedly compared the decaying and infertile landscape of the Fisher King’s realm with the state of contemporary society, offering a compelling juxtaposition between Arthurian legend and Britain in the wake of the First World War.

While most versions of the Fisher King myth end with order and prosperity restored, The Waste Land suggests that things are not so simple. Towards the end of the poem, it seems like the Fisher King is still fishing:

I sat upon the shore

Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

Shall I at least set my lands in order?

This ambiguity runs through the eighth season of The X-Files. Even if Doggett can find Mulder, even if he can resurrect the show, then what happens next? Where does it go? Is The X-Files rendered a waste land?

The eighth season is a fascinating watch, because it doesn’t seem like the show ever really has all the answers in this regard. It is never entirely clear if the inevitable resurrection of Mulder will be enough to save the show in the long-term, to render it sustainable or stable. The show itself has as little idea as the audience, and it seems like those anxieties and uncertainties play out across the eighth season as a whole. This is a version of the Fisher King that could play out as Wagner’s Parsifal or Eliot’s The Waste Land. There is no way to know which at this point.

That makes it all the more exciting and compelling.

You might be interested in our reviews of the eighth season of The X-Files:

- Within

- Without

- Patience

- Roadrunners

- Invocation

- Redrum

- Via Negativa

- Surekill

- Salvage

- Badlaa

- The Gift

- Medusa

- Per Manum

- This is Not Happening

- X-tra: The Lone Gunmen – Pilot

- DeadAlive

- Three Words

- Empedocles

- Vienen

- Alone

- Essence

- Existence

Filed under: The X-Files | Tagged: appropriation, arthurian legend, continuity, crossover, doggett, frank spotnitz, grail legend, mulder, Native American, political correctness, Slavery, the fisher king, the lone gunmen, the x-files |

Leave a comment