You’re going to go back in time? How can you do that?

Extremely well.

– Bennett and the Doctor lay down some ground rules

Part of the thrill of the ninth season is the ambition and experimentation involved.

As a rule, the Moffat era has tended towards compression, favouring individual episodes over epic two parters. While the final stories of Davies-era seasons tended to burst at the seams, with extended runtimes pushing stories beyond even the generous runtimes of two- (or even three-) part episodes, the Moffat era has favoured the standalone story. Moffat finalés are packed tight, with episodes like The Wedding of River Song and The Name of the Doctor feeling like they might come off the rails if they moved any faster.

Constructed an entire season of two-part episodes represents a very clear change in how Doctor Who is telling stories. The change in the type of story alters both the fundamental structure of the episodes and the underlying rhythm of the season. There is no precedent for this in the ten years since the show came back, which makes it all very exciting. The show has told multi-part stories before, but always as events rather than as default. It feels entirely appropriate that Under the Lake sets up quite a distinct and delineated two-part adventure.

Toby Whithouse is one of the most traditionalist writers working on Doctor Who, give or take Mark Gatiss. After all, it was Whithouse who was assigned to bring Sarah Jane into the present with School Reunion during the second season. With that in mind, it makes sense that Under the Lake and Before the Flood feel a little bit like an attempt to bring a very classic multi-part structure into the twenty-first century.

There is something very traditional about the setting and premise of Under the Lake. It is a classic “base under siege” template. The Doctor neatly summarises the situation, observing that they are “under water. Some sort of base.” It is a “base under water under siege” story. In fact, the Arthurian connotations of the title would seem to suggest an obvious pun – this might well be a “base under siege perilous” story. The set up and structure of the story is very much a classic approach to Doctor Who.

The episode clearly draws from across the continuity of Doctor Who. The idea of placing the Doctor “under water in a nuclear reactor” seems like a nod to the infamous Warriors of the Deep story, the classic Peter Davison serial that was ruled unfit for broadcast by the BBC. The idea of an ancient evil tied to a rural community in the eighties also evokes The Curse of Fenric. Whithouse’s script is quite candid about its influences and inspirations. In the teaser, it is suggested that the recovered craft “might have been here since the nineteen eighties.”

Younger viewers without a broad appreciation of the show’s history will recognise traces of The Impossible Planet and The Satan Pit in the basic set-up, as a cast of likable characters are menaced by an impossible adversary in a remote location. There is an ancient evil at work that is conscious manipulating members of the base stuff into serving its nefarious purposes. This is not to suggest that Under the Lake is derivative; there are far worse stories upon which to draw. It is merely to illustrate that Whithouse’s adventure is rooted in the show’s history.

“Base under siege” stories tend to be rather traditionalist in their structure; that is what makes them such a staple of Doctor Who, and what also makes certain sections of the Patrick Troughton era exhausting when enjoyed in quick succession. Episodes like Midnight demonstrate that it is possible to subvert the formula, but a rich history of classic stories like The Horror of Fang Rock and Pyramids of Mars suggest that there’s nothing wrong with a straightforward no-frills-attached approach.

Understanding the nature of the Doctor Who subgenre, Whithouse also draws from all manner of classic horror formulas in constructing the story. Under the Lake is populated with recognisable story beats and character archetypes drawn from across the length and breadth of classic horror cinema. (The shout-out to Cabin in the Woods seems rather spot-on in that regard.) Whithouse gets credit for the absurdly exaggerated capitalist character who plays as a parody of Burke from Aliens. “If it all goes pear-shaped, it’s not them who lose a bonus.”

However, perhaps the most strikingly traditionalist aspect of Under the Lake is the idea that seems the most novel in the context of the revived series. With School Reunion, Whithouse proved quite adept at updating classic pieces of Doctor Who for the new millennium. Not only did Whithouse introduce an entire generation of new fans to Sarah Jane, but he also made K9 cool in the context of a show that had made a point to mock the classic Cybermen design in Dalek only a year earlier.

The cliffhanger to Under the Lake suggests that the basic set up of Before the Flood is going to be more complicated than “more base under more siege.” The climax features the Doctor using the TARDIS to escape the base and travel back in time to investigate the events leading to the status quo in Under the Lake. On the surface, this is a very “timey wimey” two-part structure; however, there is something more old-fashioned happening under the hood as Whithouse takes advantage of the split between the two halves of the two-parter to change the story setting.

In short, Whithouse is basically applying the classic “two-parter/four-parter” split that many classic Doctor Who writers would employ where drafting six-part Doctor Who episodes. The most striking example is perhaps Seeds of Doom, where the Doctor spent two episodes playing Who Goes There? in the Antarctic before jumping to an estate in England for the remained four parts. It was a great strategy for keeping things interesting and moving while telling the same story over six weeks.

Although the revived show has played with the structure of two- (and three-) part episodes, most of that has involved spending the first episode building towards a climax that actually sets the meat of the story in motion. Army of Ghosts builds to the reveal of the Cybermen and then the Daleks; Dark Water spends most of its runtime affectionately mocking the fact that the Doctor has to be surprised by the reveal of the Cybermen and the Master at the climax. This is just the structure of two-parters built from forty-five minute episodes.

The only time the revival ever really changed settings during a multi-part story was between Utopia and The Sound of Drums, but that was part of a clever bait-and-switch whereby Utopia was not advertised as the first part of a three-part story. However, the idea of the Doctor essentially dropping out of one story at the end of one segment of a multi-part story and dropping into another interconnected story at the start of the next segment feels playful and subversive. It is something the classic show did rather well, and it is interesting to see the modern show attempt it.

However interesting that climax may be in the context of contemporary Doctor Who, the rest of Under the Lake ticks along like clockwork. There are spooky ghosts and high-stake chases. The environment is interesting enough on its own terms. The characters are archetypal and yet reasonably well-shaded. The fact that it all feels a little familiar is not necessarily a bad thing. The Magician’s Apprentice and The Witch’s Familiar were packed full of bold ideas and clever concepts, but their structure was haphazard and messy. Under the Lake is altogether more structured.

Whithouse does seem to run into both when it comes to characterising the Twelfth Doctor. There are points where it seems like Under the Lake has substituted in the character of Gregory House for everybody’s favourite Time Lord, to the point where it seems like the grumpy anti-authoritarian is running a differential diagnosis on a paranormal phenomenon. It is not too difficult to imagine the Twelfth Doctor breaking out a whiteboard and speculating that it cannot possibly be lupus.

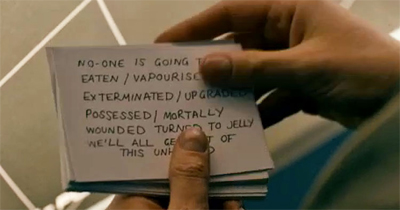

Although the broad strokes of characterisation feel just a little bit too broad, there are a handful of nice touches. Peter Capaldi is brilliant as ever, playing very well with Jenna Louise Coleman. The emotional cue card gag is hilarious, right down to the card that was clearly written for Sarah Jane. At the same time, there is something a little strange about how Whithouse writes the sequences of the Doctor interacting with the group, as if he’s not sure how to have the Twelfth Doctor take command of the situation without being overt about it.

That said, there are a number of delightfully clever ideas running through Under the Lake. Perhaps the most obvious owes a debt to Alan Moore, the idea of a supernatural and submerged small town with a paranormal secret; it recalls an early chapter of Moore’s American Gothic, which featured a submerged town of vicious and deformed vampires. (Which, come to think of it, sounds a lot like a great Doctor Who episode.) The idea of having the Doctor jump back to that town before the flood is delightfully clever.

Similarly, there is something intriguing in the use of words in Under the Lake. The mysterious inscriptions on the inside of the ship feel suitably occultish, evoking ideas of magic and mysticism. There is something suitably Lovecraftian about the idea of words as an infectious virus – something the characters absorb before they can be harnessed as “transmitters” for those words. It suggests that perhaps there is such a thing as a dangerous and insidious idea that can corrupt and contaminate without the host even realising what was occurred.

There is, of course, also something just a little sly and postmodern about it as well. Magic could (very arguably) be defined as the use of words to change reality. The Doctor suggests that the words scratched on the inside of the ship are literally magic. “The words were already in us,” he explains, attempting to articulate the danger posed by these engravings. “They literally change the way that you are wired.” How are those words any different from any other words that might change the way that a person thinks or perceives?

As with The Magician’s Apprentice and The Witch’s Familiar, eye imagery seems to be important. The episodes more than a couple of close-ups of the symbols reflected in the eyes of certain characters; that is how the infectious agent enters the body. Once the dead are resurrected as ghosts, their eyes are sunken and absent. Although some shots reveal the eye sockets to be completely empty, there are several points in the episode where the ghosts look to suffer from the same affliction as Davros.

There is also something just a little bit cheeky in the way that Whithouse presents the base itself as inherently hostile to the characters trapped within it. This is perhaps reflected in the fact that the base is a commercial institution more concerned with profit (and its own survival) than the lives of the crew. “They’re working out how to use the base against us,” the Doctor reflects of the ghosts who are manipulating the settings on the base. Later, the circuitry seems to overload and the flood doors open. O’Donnell explains, “It’s first priority is to keep the reactor cool.”

It feels like a nice commentary on the hostility of the subgenre as a whole. After all, serving on a base in Doctor Who seems to invite nothing but suffering and trauma. Making the base literally hostile (and weaponised) against the crew is just taking that subtext and literalising it. Whithouse’s script is never self-aware to the point that it becomes distracting, but it does play with the classic “base under siege” story elements even as it employs them. It is not subversive or cheeky, but it is smart in its own way.

Although the cliffhanger does tease something slightly new and exciting, Under the Lake is a more traditional and formulaic approach to Doctor Who than the season-opening two-parter. While the episode is predictable and familiar, there is something to be said for a solid execution of an old standard. Under the Lake is not among the best base under siege stories that the show ever produced, but it has fine form and sets up an interesting second part.

Filed under: Television | Tagged: base under siege, doctor who, toby whithouse, under the lake |

At first I thought Dr. House was the natural course to take. (Even if I tapped out in season three of House… it became very complacent very quickly)

Now I’m worried Moff is going to indulge his “white board” a little too often. Who needs themes emotions or a story, let’s break down the individual tropes for all the dumb-dumbs watching. (This is exactly what upset people about Cabin in the Woods.) Guess we’ll wait and see…

I thought Cabin in the Woods was fairly rapturously received, no?

That said, Whithouse’s version of the Twelfth Doctor is perhaps the only part of Under the Lake I took serious issue with. It’s like he looked at a photo of Peter Capaldi and heard the performance described third-hand before writing those scenes. (But, hey, I liked the emotional cue cards.)

Edit: By “complacent”, I meant the show became less about

“this is a story about a patient who lies to his doctors and to himself”

and more about

“this is Hugh Laurie farting around a bland set and tweaking peoples’ noses”.

Personally, at the risk of derailing, I’d put the decline of House at the end of the fourth season. House’s Head/Wilson’s Heart are perhaps my favourite episodes of the show, but it’s all downhill from there. But those are phenomenal pieces of television.

I apologize for the derail. 🙂 The premieres and finales were like watching an entirely different show, no? Whether that’s an indictment of the show’s quality or not is up you.

Don’t apologise for the derail! That’s what comment threads are for. (Also: why I make the worst podcast guest ever.)

But I liked all of the fourth season of House leading up to the finalé, even allowing for the writers’ strike. I really liked the idea of “auditioning” replacements for the three sidekick characters, and doing it with a much larger pool opened up all sorts of fun dynamics. I think once the show got past that and settled back into “House is a jerk with three side kicks”, it never quite recovered.