To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the longest-running science-fiction show in the world, I’ll be taking weekly looks at some of my own personal favourite stories and arcs, from the old and new series, with a view to encapsulating the sublime, the clever and the fiendishly odd of the BBC’s Doctor Who.

Blink originally aired in 2007.

But listen, your life could depend on this. Don’t blink. Don’t even blink. Blink and you’re dead.

– the Doctor

Like Love and Monsters, Blink is a “Doctor-lite” episode, an effective time- and money-saving measure from the show’s production staff, built around filming an episode that requires the minimal involvement from the lead actors. Also like Love and Monsters, Blink is an episode of Doctor Who that is about Doctor Who.

Granted, Steven Moffat’s script doesn’t engage with fandom as directly as Russell T. Davies did. Here, the fans trying to find their own meaning in the show are the anonymous net-izens on forums and fan sites, rather than a friendly group of eccentric individuals enriched by contact with one another.

While Love and Monsters is about how Doctor Who fandom tends to serve to unite diverse people beyond an interest in Doctor Who itself, forming bonds that become more significant and important than the interest in the show, Blink is very much a story about trying to make sense of the show itself.

Love and Monsters is very much anchored in the classical fan tradition, dating back to the classic show. Elton’s memory of the Doctor is faintly recalled from childhood. There’s a sense that he recalls a mood and the character better than he can remember the narrative or the details. Elton is a character who grew up after a chance encounter with the Doctor when he was younger, and who saw that shape his life.

Elton’s fandom was distorted when Victor Kennedy arrived and tried to turn LINDA into a unit of information-gathering kill-joys. There was a sense that nobody involved with LINDA really had a holistic understanding of the Doctor, with their vision of the character drawn from little snippets caught here or there, and “super fan” Victor arriving with the promise of more information and more material relating to the Doctor.

In short, Love and Monsters was really based on a traditional model of Doctor Who fandom, one which probably existed before the DVD revolution made it possible to analyse the show frame-by-frame and relatively easy to own a significant portion of it. Victor’s information on the Doctor could only really hold sway in an era before the internet made access to such information more democratic and widespread.

In contrast, Blink is very much the story of modern fandom. It’s the story of how people can pick apart every single frame of the show that they love, and how people can delve even deeper into the source material than ever before. DVD “easter eggs” are a vital plot point, and the show’s rather iconic video recording is even available on the third season DVDs as an “easter egg” itself. Lawrence is introduced as a likeable obsessive who has poured hours and hours into his analysis of the Doctor’s recordings.

Blink repeatedly calls attention to just how much Lawrence is communicating in the language of modern fandom, a group ready to pick apart every sentence or hint or piece of subtext looking for a deeper meaning that isn’t there. After the Doctor advises him to look to the left, Lawrence delves right into an absurdly abstract political reading. “What does he mean by look to your left?” he ponders. “I’ve written tons about that on the forums. I think it’s a political statement.”

Later in the same conversation, Moffat suggests that the Doctor has created his own memes, a cottage industry of fans echoing and repeating his phrases as some sort of in-joke. “The angels have the phone box,” Lawrence repeats at one point. “That’s my favourite, I’ve got it on a t-shirt.” In a very real way, Blink is an exploration of how home media has changed since the show went on the air, and how that has really changed the way that we understand and talk about Doctor Who.

After all, it’s telling that the Doctor is sent back to 1969. It was the last year with any completely missing Doctor Who material. After that, every broadcast serial was recorded and preserved and maintained. It wasn’t always readily available in colour, but everything from Jon Pertwee’s first season and onwards is available to fans in one way or another. While the classic Doctor Who DVD line was still being released in 2007 when Blink broadcast, we were definitely moving towards a word where Doctor Who was readily available to everybody and anybody to pour over.

Moffat is a writer best known for his “timey wimey” scripts. There’s no denying that his work on Doctor Who makes great use of the show’s central time travel set-up. Blink is itself a rather cleverly constructed time-travel narrative, with all the elements moving in something of a loop, with the final scene tying up all necessary loose ends by having Sally give the Doctor all the necessary information before he encounters the Weeping Angels in the first place.

However, there’s also a sense that Moffat is playing with the strange piece of time travel that occurs every time that a fan sticks on a classic DVD, re-watching and re-engaging with a story that is decades old. We’re watching it in 2013, but it is a piece of far older history. There’s a strange dissonance there, as we try to put it all in context, and to understand it outside of its original air date. Who is to say that we can ever fully understand the nuance and complexity lurking between the lines? Is it possible that we bring too much modern baggage with us?

It’s all relative. When Sally receives the letter from Kathy, we’re reminded of this strange disconnect – this was a letter written decades ago, but it’s immediately relevant to Sally. It’s part of her time-line, her version of events. It is part of her present, and can’t really be separated from that. Sally can’t help but react to this twenty-year-old letter in the light of her immediate surroundings. It’s a very interesting and very clever idea.

As much as Moffat likes to play with time, he’s also a writer who engages with technology. In particular, Moffat’s scripts tend to be built around broken or malfunctioning technology – stuff that is trying to work, but is failing badly. The surgery units that try to put a little boy back together; the repair robots working on a stranded ship; the communications technology that retains the faint echo of long-dead people, and the library computer that “saved” them.

In Blink, it’s interesting that the Weeping Angels aren’t really an example of glitchy technology. Instead, the Doctor himself is presented as a ghost in the machine. The DVD player won’t even properly pause when he’s on the screen. “He’s like he’s a ghost DVD extra,” Lawrence helpfully explains. “Just shows up where he’s not supposed to be.” Indeed, up until the final scene, Sally spends most of the episode interacting with echoes of the Doctor – DVD recordings and holograms. The day is saved by the TARDIS DVD player.

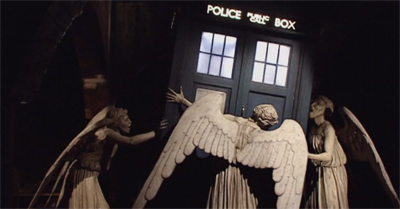

Still, the Weeping Angels remain a rather brilliant idea, even if they’ve been somewhat diminished by their frequent reappearances. They work on several levels. On a rather basic level, they are pretty much perfect Doctor Who monsters. Like a lot about this episode, they call attention to the nature of the show itself, and the Weeping Angels are pretty much the best budget-saving monsters ever created.

These element leans as heavily on the fourth wall as Billy Shipton’s observation about the design of the TARDIS. “But this isn’t a real one,” he informs Sally as he shows her the TARDIS. “The phone’s just a dummy, and the windows are the wrong size.” He’s echoing a particularly hardcore fan complaint about the famous blue box. Similarly, Lawrence’s co-worker is able to provide some great plot advice as he enthusiastically watches a horror film. “Go to the police, you stupid woman. Why does nobody ever just go to the police?” These elements draw attention to the fictional nature of the show, just as the design of the Weeping Angels does.

The Weeping Angels are defined so that they can’t move on screen. They look like statues. They only move when the audience isn’t looking, which is a great way to make them effective. All you need is models and actors who can hold perfectly still for a few frames. These are creatures that could easily have been created for the classic series, and could easily have been terrifying without a large production budget.

More than that, though, their entire gimmick is based around terrifying the audience who know they are watching a television show. These monsters move when you aren’t looking. So covering your eyes or cuddling into a cushion or even hiding behind the sofa are all poor choices. The only chance of survival that you have is to keep watching. (Which also makes then effective villains for an episode about obsessive Doctor Who fans.)

That said, I’ve always been a bit curious about the Weeping Angels. The Doctor identifies them as “creatures of the abstract. They live off potential energy.” They feed off the potential future that they deny a person by sending them back in time. “The rest of your life used up and blown away in the blink of an eye,” the Doctor explains. “You die in the past, and in the present they consume the energy of all the days you might have had.”

This is a great hook, but it raises all sorts of questions – particularly since the victims all seem to have gone on to live full and happy lives. Does that suggest that humans are creatures with infinite potential? This would certainly make sense of the “battery farm” approach adopted by the Angels in The Angels Takes Manhattan. It’s a great idea, and it’s no surprise that the Weeping Angels stand as Moffat’s most successful creation.

That said, The Time of the Angels does undermine a lot of the work done here in its attempt to expand and deepen the mythology of the creatures. The notion that the idea of a Weeping Angel becomes a Weeping Angel is ingenious, confirming the “creatures of the abstract” definition, but the decision to film the creatures moving undermines one of the smarter aspects of Blink. Unspoken in the episode itself, Blink leaves the viewer the impression that the camera (and the viewer) also exercise control over the Angels’ “quantum lock.” The implication is that the very fact that we are watching impacts whether they can move.

Still, Blink presents the Weeping Angels as an absolutely fantastic creation. Director Hettie MacDonald does wonderful work here, particularly at the episode’s climax. It’s a shame that the show never recruited her again – that great shot of the TARDIS being rocked back and forth by the mob of angels as the light dims and brightens is gloriously evocative. The sequences where the Angels advance on Sally on Lawrence is also incredibly tense.

Despite that, there are some problems with Blink that peek through. It remains one of the most intelligent and accessible episodes of the revived series, but there are moments that feel a little too uncomfortable. These lurk at the edges of the script, and really become problems in a larger context, when looking at the whole of the Davies era or of Moffat’s writing in general. Individually, these elements feel relatively innocuous, but taken collectively, they become something larger.

It falls back on the Davies-era “women get their happily ever after by finding a man” cliché with a little too much ease. (See: Rose, Martha, Donna.) When Kathy is sent back in time, the episode informs us that she lived a good life. “Don’t feel sorry for me,” she tells Sally. “I have led a good and full life. I’ve loved a good man and been well loved in return.” Similarly, Blink ends with Sally paired up with Lawrence and living happily ever after in his video shop.

In contrast, the male characters seem to believe that more is required. While Detective Shipton gets married, it’s notable that there are no extended family members to keep him company in his final hours. Unlike Kathy, Shipton is allowed to have his own career and his own life outside of family. Look at the way that the plot treats their attempts to interact with Sally and influence her investigation. Kathy has children so that one of their children can give Sally a note telling her she had a good life; Billy Shipton “got into publishing; then video publishing; then DVDs, of course”, so he could deliver the Doctor’s message to her.

Blink also continues the rather uncomfortable trend of comparing Martha to Rose and making it seem like Martha never had a good time in the TARDIS. She references visiting the moon landing “four times”, but there’s a sense that Martha’s experiences are 1969 are quite similar to her experiences in Human Nature and Family of Blood. She does all the hard ground work in the background while the Doctor gets something of an easy life.

Indeed, the episode suggests another unfortunate comparison to Rose for Martha. Rose began as a shop assistance and then got become something much more meaningful and important as a result of travelling with the Doctor. Martha was studying to be a Doctor herself, and her penultimate adventure in the TARDIS has her working as a shop assistant. To be fair, the show does repeatedly make a point of how Martha suffers in silence, and how awesome she is, but it can;t help but seem a little mean-spirited.

I get that the third season is consciously trying to work through Rose’s departure, which was a pretty monumental moment for the revived series. At the same time, spending a whole season with a companion whose defining characteristic is “not!Rose” and who seems to have a pretty crap time of her travelling in the TARDIS does sting just a bit. Martha’s character arc, both in the third season and beyond, is a bit of a mess.

Still, Blink remains a wonderfully constructed episode, and an insightful exploration of the relationship between fans and the show. It’s a deftly-written and cleverly put-together adventure that remains one of the highlights of the new series, even as it does point to some of the underlying issues with this period of the show’s history.

Filed under: Television | Tagged: arts, bbc, blink, doctor, Doctor Who fandom, DoctorWho, DVD, Easter, fiction, Moffat, Online Writing, russell t. davies, Sally Sparrow, science fiction, steven moffat, Weeping Angel |

“Blink” is my favourite of the modern Doctor Who episodes although I agree that it has the weaknesses you identify. The Manhattan episode resolves some of these, but not all. Thanks for a great review that provoked me to think more deeply about the underlying issues.

It’s a great little episode, even with those problems, I think.

The Weeping Angels are terrifying. I think this episode did a brilliant job of introducing them, and I never really thought about the points you brought up until now…think I’m going to have to try to rewatch the episode!

Oh, and the statues used at the end are ones from Cardiff. When the episode aired, some of the statues were on my daily route to work, and I’d see the rest just out and about around town. I’ve never looked at those statues in the same way again.

They are a great monster, aren’t they? That said, I think seeing them move was a bit of a mistake in The Time of the Angels/Flesh and Stone.