To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the longest-running science-fiction show in the world, I’ll be taking weekly looks at some of my own personal favourite stories and arcs, from the old and new series, with a view to encapsulating the sublime, the clever and the fiendishly odd of the BBC’s Doctor Who.

Forest of the Dead originally aired in 2008.

Everybody knows that everybody dies. But not every day. Not today. Some days are special. Some days are so, so blessed. Some days, nobody dies at all. Now and then, every once in a very long while, every day in a million days, when the wind stands fair, and the Doctor comes to call, everybody lives.

– River brings Moffat’s contributions to the Davies era a full circle

There’s actually quite a lot to like about Forest of the Dead. Like Silence in the Library, it doesn’t really push Moffat’s work on Doctor Who that much further. A lot of its big ideas can be found in Moffat’s earlier Doctor Who work. Still, it is quite clever and quite well-written, and a pretty well-constructed episode. This is, after all, the last episode of the Davies era that is not credited to Davies himself. Given it’s written by the showrunner elect, that celebratory feel is justified.

At the same time, however, there are some very uncomfortable gender roles at work in Forest of the Dead for female characters like Donna or River. Moffat would come under a lot of fire during his tenure producing Doctor Who for the way that he wrote female characters, but I’d actually argue that the problems with Forest of the Dead are more in keeping with wider Davies-era trends towards the way that female characters are written.

A lot of the problems with Forest of the Dead can be traced back to the fact that Moffat really has no idea how to write Donna Noble as a character. It’s worth conceding that the only episode to feature Donna that would have aired when Moffat wrote Silence in the Library and Forest of the Dead would have been The Runaway Bride. Donna was a very different character in The Runaway Bride, more like a Catherine Tate comedy sketch than a fully-formed character – a “Bridezilla” that was fleshed out by Davies’ writing and Tate’s surprisingly nuanced performance.

Forest of the Dead seems pitched towards that version of Donna, rather than the version of Donna that held the Doctor to account in The Fires of Pompeii or The Doctor’s Daughter. Steven Moffat’s Donna is apparently still searching for a man to give her life meaning, despite the fact that Davies went out of his way in Partners in Crime to explain that she was looking for the Doctor, not for a man. (When she says she’s looking for “a man”, she has to correct Wilf, “I don’t mean like that!”)

Here, Moffat suggests that Donna’s perfect world is a world where she’s happily married and has two kids to look after. More than that, though, he suggests that Donna is really just an obnoxious loud-mouth who dreams of a quiet and subdued man she can completely dominate, somebody who is “gorgeous and can’t speak a word.” The episode even turns this into a bit of a joke about Donna. “I made up the perfect man,” she tells the Doctor. “Gorgeous, adores me, and hardly able to speak a word. What’s that say about me?” The Doctor replies, “Everything… Sorry, did I say everything? I meant to say nothing. I was aiming for nothing. I accidentally said everything.”

Rather like the way that the climax of Silence in the Library hinged on the Doctor unceremoniously dumping Donna back in the TARDIS so he could continue his adventure with River Song, this suggests that Moffat is having a great deal with trouble with the character of Donna Noble. Moffat hasn’t had any trouble writing Rose Tyler. Martha was a fairly small part of Blink, and it seemed like a lot of writers had problems with her. Moffat has also written his own companions very well.

Still, it seems quite fair to say that Donna is quite far outside Moffat’s ideal companion range, with the producer going on record and arguing that the role of the companion pretty much has to be filled by young attractive women:

Who’s going to do it? Is it going to be a mother of 15 children? No. Is it going to be someone in their 60s? No. Is there going to be a particular age range? I mean… who’s going to have a crush on the Doctor? You know, come on!

It’s a very close-minded view of who a companion should be. The Davies era was never especially radical when it came to companions, although it does get credit for inviting the first minority companions on the show. And, while Donna was the only long-term companion to fall outside the “young pretty woman” bracket, Davies did recruit David Morrissey, Lindsay Duncan and Bernard Cribbins as companions for his season of specials.

Even outside of the trouble writing Donna as a character – turning her into an exaggerated has-to-be-right completely-dominates-the-men-in-her-life caricature – Forest of the Dead falls into some familiar Doctor Who gender issues. It seems to suggest that all that major female characters need to keep them happy is a man in their life and children to look after. Not only is Donna’s false reality built around caring for two young children, but River Song’s happy ending sees her becoming a care-giver to three little kids.

This is point where I have to talk about Steven Moffat and sexism, because it’s such a big thing. It’s hard to ignore, and hard to avoid. “Moffat is sexist” has become almost internet shorthand, a rather frequent attack on his tenure as showrunner. It’s something that got so bad that the writer was forced off Twitter by those accusing him of being a “sexist bastard.” Of course, the concerns about gender roles in his version of Doctor Who is legitimate, but casually throwing accusations like that around is hardly constructive.

Moffat’s case isn’t helped by a random selection of quotes and interviews in his past, mainly taken from editorialised interviews, where context is quickly lost. Talking about the outlook of a character in Coupling, and discussing his own early life and lad culture, Moffat made the mistake of offering a variety of quotes that could be crudely snipped together to form the following manifesto:

There’s this issue you’re not allowed to discuss: that women are needy. Men can go for longer, more happily, without women. That’s the truth. We don’t, as little boys, play at being married – we try to avoid it for as long as possible. Meanwhile women are out there hunting for husbands. The world is vastly counted in favour of men at every level – except if you live in a civilised country and you’re sort of educated and middle-class, because then you’re almost certainly junior in your relationship and in a state of permanent, crippled apology. Your preferences are routinely mocked. There’s a huge, unfortunate lack of respect for anything male.

There are some less-than-endearing ideas expressed in there, but it is worth giving Moffat a bit of the benefit of the doubt. This is an out-of-context cobbled-together quote from an interview that has already been tailored and edited by the interviewer in question. A lot of nuance is lost in translation, and it’s a wholly different thing from having Moffat just say those things strung together as a sentence.

Even with all of that in mind, it is very hard to get past that, particularly when quotes and comments are constantly circulating from a variety of sources. Particularly relevant here is another of those circulating Moffat quotes. “A young married couple without a kid?” he asks. “They’re just dating. You tell yourself you’re married, but really you’re dating.” I’m vaguely troubled that I can’t find an official source for it, or even a proper citation, but it does fit with some of the gender issues I have with Moffat’s writing.

Here, Donna’s perfect life sees her married with kids. Forest of the Dead teases the idea that the Doctor and River Song are married, a theory later confirmed with The Wedding of River Song. However, her happy ending involves her caring for three kids. In Asylum of the Daleks, Amy acts like her marriage to Rory is rendered invalid by the fact that she can’t have children together, even if the pair work through that in the end. Perhaps it’s a sign of Moffat recognising criticism of his writing and trying to work past that.

And I give Moffat credit for that. After all, for all these legitimate concerns about Moffat’s attitudes towards female characters and marriage are raised, he does seem to try to get better. Most notably, Moffat took on board criticism about the lack of LGBTQ representation in his first year of the show, and developed three major supporting characters to help remedy that. Indeed, it’s worth reflecting on Philip Sandifer’s insightful argument that, with The Empty Child, “it is Moffat, not Davies, who is responsible for introducing a raftload of queer content to Doctor Who.”

And all of this is getting a bit away from the primary problem with Forest of the Dead. The gender issues in Forest of the Dead have to do with treating marriage as the end of the line for female characters, treating it as a happy ever after. To put it rather bluntly, this is more of a problem with the Davies era as a whole than it is with Steven Moffat’s body of work. Amy Pond and River Song get to be kick-ass heroines long after they get married. Indeed, the bulk of Amy’s appearances come after she is married.

It’s also worth noting that Moffat’s companions have more active lives outside the Doctor. In the seventh season, Rory and Amy and Clara are all part-time companions. None of them are as defined by the Doctor as Rose or Martha. It almost seems like a response to Sarah Jane’s criticism of the Doctor in School Reunion, of the character’s tendency to pick up pretty young women, dominate their lives and then kick them out of the TARDIS with no life to get back to apart from him. All the long-term female companions in the Davies era of the show are defined by the Doctor, even after their time traveling with him.

While Amy and Rory wind up together and happy, even if isolated from everybody that they love, there’s no indication that the rest of their lives will be devoted to hunting down the Doctor. Davies’ female companions are defined by their inability to let go. Martha runs off and gets engaged to a doctor. Donna hunts down the TARDIS. Rose breaks down the walls of reality to save the world, but also to reunite with her sweetheart. In contrast, Jack desperately wants to reunite with the Doctor in Utopia, but he seems able to let him go at the end of The Last of the Time Lords.

In the context of Forest of the Dead, it’s worth noting that it’s the Davies era which treats “… and then she got married” as the default way of demonstrating a female character had a happy ending. Rose got her whole family reunited, a meaningful job and the joy of playing the role of the Doctor, but her character arc comes to an end when she finally gets a copy of the Doctor she can marry and grow old with. The show demonstrates that Martha “got over” the Doctor by getting engaged to Tom Milligan and marrying Mickey Smith. In The End of Time, Part II, the Doctor takes some solace in the fact that Donna finally gets married.

In contrast, the male companions of the Davies era don’t need those sorts of happy endings. Adam and Jack are both dumped from the TARDIS in the first season. Mickey leaves to take care of his grandmother, and comes back when she passes away. Jack returns, desperately clinging to the outside of the TARDIS, only to leave to work with the Torchwood team. While the Doctor does set up a romantic pairing for Jack at the end of The End of Time, Part II, it feels more like a one-night stand than a wedding proposal.

So the gender issues in Forest of the Dead seem to have more to do with the context of the wider Davies era than they do with the still-to-come Moffat era. This doesn’t excuse them, and it doesn’t let Moffat entirely off the hook, but it does add some element of context. I do think that the Moffat era features some highly questionable gender-related moments, but I also think that the Davies era did as well. I don’t think that Moffat or Davies were inherently sexist, and I certainly don’t think that there’s any sinister agenda there, but I do think there are elements that crept into scripts and scenes that really shouldn’t have.

It is worth noting that all these problems come to the fore in the two-parter where Moffat introduces the character of River Song. River Song is a character who tends to draw a large amount of criticism from on-line fans, many objecting to her “special” relationship with the Doctor, or finding her annoying or over-emphasised or over-used. Many of the same people who will accuse Moffat of sexism will then go on to criticise his use of River Song.

Personally, I love the character of River Song. How many legitimate action hero roles are written for women at forty-five? The only similarly high-profile television role I can think of at the moment is the casting of Ming-Na Wen as Melinda May in Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. More than that, though, River Song is a confident and sexually-active forty-five-year-old woman. She’s just as flirty and roguish as Captain Jack. Indeed, given the parallels between Moffat’s first two-parter of the Davies and the last two-parter of the Davies era, it’s quite clear that River Song is written in much the same style as Captain Jack was.

The only substantial difference is that Jack is a handsome thirty-something bisexual man and she’s a pretty forty-something bisexual woman. Much is made of her relationship with the Doctor, but Moffat makes it quite clear that River and the Doctor aren’t in anything approaching a conventional relationship. The Doctor is free to have his own flirtations – with the TARDIS (“sexy”) identified as his wife – and River is free to have hers.

Moffat makes it quite clear here that River is what John Barrowman has defined as “omnisexual.” When Lux asks why he’s the only member of the team (involving male and female characters) wearing a helmet, River flirtatiously replies, “I don’t fancy you.” When Anita wonders how River can know that the Doctor and Donna aren’t androids, River replies, “Because I’ve dated androids. They’re rubbish.” Of course, given that Moffat ties River into the Doctor’s personal story arc so tightly, these elements aren’t as heavily emphasised as they would be with Jack. It’s not like River got her own spin-off with sex aliens and sidekicks and so on.

Which brings us to the accusation that River’s whole life revolves around the Doctor, and that this somehow invalidates her as a character. That’s not entirely fair. The show is about the Doctor. He’s the narrative constant. It’s really about other characters drawn into his narrative gravity. The Davies era defines Rose by her creepy dependency on the Doctor, and Martha by whether she’s currently “over” the Doctor or not. In Partners in Crime, Donna actively seeks the Doctor out. Companions get to have their own story arcs and character moments, but these inevitably hinge on the Doctor, because he’s the one with the time machine and the whose name appears in the title.

This is just the more obvious with Moffat’s companions because he likes to play with time. Moffat is interested in the storytelling potential of a time machine. So instead of one concentrated year-or-two spell (and, in the case of Martha and Rose, a long time thereafter), Moffat’s companions see their entire lives dominated by the Doctor. He visits Amy when she’s very young, and returns to her in adulthood. He keeps intersecting with River over the course of her life. As a result, every time we see River, she’s drawn into his narrative, defined by that.

So the exposure to the Doctor seems longer. It stretches across their entire lives, rather than being something that happens to them when they are twenty-something. As such, it’s easy to understand the “Moffat’s female characters revolve around the Doctor”, even if – in practise – the same is very true of Davies’ Doctor Who.

Again, to be fair to Moffat, he does make it clear that River Song has her own life outside of her adventures with the Doctor. “Oh, no, no, no, no,” the Doctor protests as River attempts to sacrifice herself. “Come on, what are you doing? That’s my job.” River protests, “Oh, and I’m not allowed to have a career, I suppose?” It’s worth noting that River is more prone to calling the Doctor than he is to summon her. This might be his story, but he’s at her beck and call.

Outside of all this complicated (and somewhat muddled) gender stuff, Forest of the Dead is a very solid continuation of Silence in the Library. It continues the “Doctor Who as television show” subtext of Silence in the Library by having Cal switch from one show to another. She swaps from watching Doctor Who to watching something that looks like a soap opera, complete with wonderfully over-the-top Murray Gold theme music to clue the audience into the genre switch.

It’s worth noting that Donna’s alternate life is governed by television conventions. She finds herself disorientated by quick cuts and exposition used to convey information quickly, even drawing attention to the way the episode is constructed. “How did we get here?” she asks Doctor Moon. “You said river, and suddenly we’re feeding ducks.” It turns out that we’re watching Donna’s imaginary life unfold in something approaching real time, as Miss Evangelista points out, “You didn’t get my note last night. You got it a few seconds ago. Having decided to come, you suddenly found yourself arriving. That is how time progresses here, in the manner of a dream.”

It’s also good television writing – no padding, quick cuts, clever structure. Once a character makes a decision, the show doesn’t linger on it that much longer. It’s worth pointing out that Donna effectively figures out the world isn’t a real using the same logic she could use to figure out she’s in a television show. Miss Evangelista points out that there are really only two children around, and they all look the same. Using that logic, Donna could easily start noticing that many of the extras in crowd scenes have been duplicated or recur.

There’s also a nod to the fairy tale style that Moffat would adopt when he took over the show, a thread dating back to The Girl in the Fireplace at the latest. Here, again, the Doctor is defined as a story rather than a man or even a god. “He’s the Doctor,” River tells Lux at one point. “And who is the Doctor?” Lux asks. “The only story you’ll ever tell, if you survive him,” River replies.

(Speaking of fairy tales, I do like how Moffat riffs on the familiar “Walt Disney” urban myth here. The Lux Corporation are dead-ringers for the Disney family, managing a massive intergalactic attraction and vigorously defending their intellectual property rights. However, it’s revealed that a member of their family is being artificially kept alive beneath the attraction, mirroring the famous “Walt Disney is cryogenically frozen beneath the Pirates of the Caribbean” rumour.)

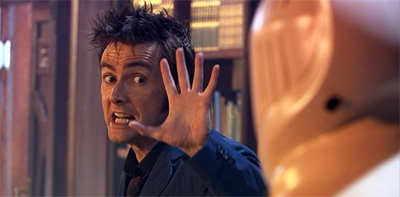

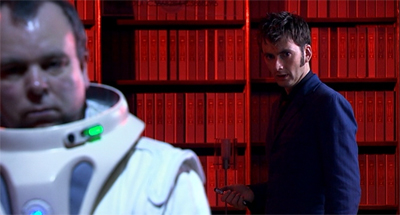

Re-watching the series, I’ve really noticed the wonderful red/blue lighting contrast that the production team seems to be pushing this season. Quite a number of episodes are contrasted with those colours. Of the two episodes broadcast after the pilot, Planet of the Ood is shot in a blue-ish hue, in contrast to the strong reds of The Fires of Pompeii. The Fires of Pompeii are shot in red in contrast to the blues of Waters of Mars, two episodes intended to contrast one another. Midnight is definitely framed in calming blue in contrast to the more earthly reds of Turn Left, contrasting with companion- and Doctor-lite episodes.

Here, the sets that were lit blue in Silence in the Library are lit red in Forest of the Dead. It’s a nice bit of visual consistency running through the season. I’m not sure it really means that much – outside perhaps emphasising the blue/brown suits that the Doctor wears and Donna’s red hair. Perhaps it’s just a variation on the familiar orange/blue trend in television/movie/poster visual design that was very popular at the time, and remains popular to this day.

I quite like Silence in the Library and Forest of the Dead, even if I can concede there are some gender issues here, and that the episodes feel like a lot of Steven Moffat’s familiar concepts were thrown in a blender. There is a lot of good stuff here, even if this two-parter doesn’t amount to the strongest story of the season. It’s clever and well-written, even if that is undermined by a few unfortunate decisions from Moffat. It’s worth reflecting on the fact that this is the last episode of the Davies era to be written without a credit to Davies. It’s not a bad way to go out.

You might be interested in our other reviews from David Tennant’s third season of Doctor Who:

- Partners in Crime

- The Fires of Pompeii

- Planet of the Ood

- The Sontaran Stratagem/The Poison Sky

- The Doctor’s Daughter

- The Unicorn and the Wasp

- Silence in the Library/Forest of the Dead

- Midnight

- Turn Left

- The Stolen Earth/Journey’s End

Filed under: Television | Tagged: arts, bbc, Davies, doctor, DoctorWho, Donna, Donna Noble, fiction, Forest, Forest of the Dead, Moffat, Online Writing, River Song, River Song (Doctor Who), rose tyler, science fiction, steven moffat, tardis |

Leave a comment