The X-Files is somewhat fascinating as a historical artifact, a prism through which the viewer might explore the United States in that gap of time between the end of the Cold War and the start of the War on Terror. The show serves as something of a travelogue through the American subconscious, a vehicle for the nation’s fear and anxieties. It might be quaint now to look back on the show’s depiction of mobile phones and the internet, but The X-Files offers a snapshot of an America just on the cusp of that technological revolution, when there were still dark shadows and corners of the continent to be probed and explored.

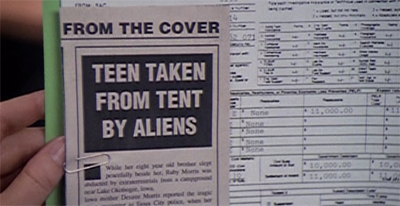

One of the more interesting aspects of The X-Files is the way that it deals with faith in the nineties. Scully’s attempts to reconcile her religious beliefs with a rational approach to the universe are surprisingly insightful and nuanced, but Mulder’s belief system also offers a vehicle to explore the form that faith might take. “I want to believe,” Mulder confesses at the end of Conduit, with the iconic poster turning the sentiment into a motto. It doesn’t matter that Mulder chooses to invest his faith in aliens or conspiracies, The X-Files is still an exploration of what faith meant in the nineties.

The nineties were a very weird time. America was the only superpower, and no real threats loomed on the horizon. The Gulf War hadn’t really been spawned by a direct or philosophical threat to the American homeland, and the spectre of communism had been vanquished as the Berlin Wall fell. Chris Carter seemed to hone in perfectly on the national mood when crafting The X-Files. Without any major outside threat, America became a bit more reflexive, looked inwards just a little more.

Religion is obviously a fascinating way of looking at a particular culture, and it would seem that American in 1990s was going through something of a spiritual crisis. In 1989, George Gallup and Jim Castelli published The People’s Religion: American Faith in the Nineties. The book suggested that America’s religious beliefs had remained remarkably constant in the fifty years between 1939 and 1989, throughout the Second World War and the Cold War.

The picture during the 1990s is quite different, and suggests that significant changes were taking place. The number of atheists and agnostics in America jumped significantly in the 1990s, but attendance at conservative religious institutions also increased significantly in the same period. Culture Wars notes that – following a collapse at the end of the eighties – televangelism experienced a resurrection in the mid-nineties. The Encyclopaedia of Protestantism suggests that televangelism was also so energised that it began to extend outwards from the United States.

Indeed, the Christian Reconstructionism of the 1990s helped the Religious Right recover from some stumbling blocks in the late 1980s:

The Christian Right has shown impressive resilience and has rebounded dramatically after a series of embarrassing televangelist scandals of the late 1980s, the collapse of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, and the failed presidential bid of Pat Robertson. In the 1990s, Christian Right organizing went to the grassroots and exerted wide influence in American politics across the country.

At the same time, the way that people engaged with religion itself changed radically.

Writing about the shifting landscape of American religion in the nineties, Wade Clark Roof found that many younger people tended to engage a broader spectrum of belief, what he termed “the new spirituality”:

In my research, we asked the post-World War II baby boomers if they preferred to stick to a particular faith or to explore teachings from many traditions – and the overwhelming majority said explore. Faith is seen as a journey, not a fixed destination. The boomer generation has been more exposed to the world’s religions and spiritual teachings than any generation ever. And in a global world, pressures are strong pushing us in the direction of “cafeteria-style” religion. Twenty-two (22) percent of young adults in our study said they believed in reincarnation (Roof 1993). Even church-going is often determined on the basis of whether it contributes to spiritual growth. We asked in the survey if one should attend a church or synagogue out of duty or only if it helps one to grow – and the overwhelming majority said the latter. Even Christian evangelicals and fundamentalists are increasingly thinking this way – which simply shows the extent to which popular psychology and faith have come to be fused in the minds of believers.

In The X-Files, you could argue that Mulder’s entire conspiracy theory is religious. He just uses aliens and government conspiracies as a way of explaining the greater mysteries of his existence. Where did his sister go? Why is he confined to the basement of the FBI headquarters? How come all of his evidence disappears? Mulder unites all of these strands into his own religion, his own web.

It’s fitting that Conduit closes on the image of Mulder in church, in a pose similar to prayer. It’s not clear if Mulder is actually praying or is simply deep in thought. His subsequent attitude towards Scully’s religious beliefs would suggest the latter, but it isn’t as if Mulder’s is entirely consistent. He believes in aliens and this vast conspiracy because it is easier than facing the alternative, than coming to terms with the reality that his sister is gone and his once-promising career has collapsed because he’s just impossible to work with.

At the end of the episode, we listen to a recording of Mulder’s hypnosis session, referenced in The Pilot. Describing his sister’s abduction, Mulder talks in terms that make it clear this is a religious experience. Asked whether he is afraid, he replies, “I know I should be but I’m not.” There’s a voice, in his head. “It’s telling me no harm will come to her, and that one day she’ll return.” It’s faith. It doesn’t matter that Mulder’s faith is in little green men, it’s still something deeply important to him, something of which he has no real proof, which he uses to explain the world around him.

Of course, there’s a problem with this approach to Mulder, and – while it wouldn’t become a real problem until towards the end of the second season – you can see it developing in Conduit. Quite frankly, we know that Mulder is right. We know that his faith here is placed in something that will turn out to be true. That becomes an ironclad certainty by the time we reach Colony and Endgame, but it seems quite obvious here.

After all, if we are to accept that there’s absolutely nothing of substance here and it’s all tied together by Mulder’s sheer undeniable desire to believe in aliens, we have to overlook a whole lot of the evidence. Even Scully concedes that there’s a massive amount of suspension of disbelief required to write off things like the satellite transmission in binary, let alone the evidence that Ruby has experienced weightlessness. The deck is stacked here. We already very heavily suspect that Mulder will be correct, and – while plausible deniability still exists – Conduit makes it quite clear that Scully’s rational scepticism can only stretch so far.

Which is a bit of shame, because Conduit actually does a bunch of great stuff with Mulder as a character, as it sort of picks at the workings of our conspiracy theorist’s brain. For example, there’s a lovely introductory sequence where Blevins tries to shut down Mulder’s inquiry. Not because he fears Mulder might uncover some terrible secret, or that Mulder might reveal the conspiracy to the world. “Agent Mulder’s latest 3-0-2,” he explains to Scully, “requesting assignment and travel expenses for the both of you.” Yes, it seems quite likely that Blevins could justify shutting Mulder down for budgetary reasons.

After all, we live in an era where every public expense is scrutinised and there’s an increased paranoia about where our tax payer money is being spent. You can understand why senior FBI officials would be reluctant to let tax payers foot the bill for a trip based around the idea that a girl was abducted by aliens. While Mulder might like to believe that the powers that be are afraid of him casting his flash light into some dark corners, I can empathise with the idea of a mid-level pencil pusher wary of an expense account scam.

More than that, though, we get another demonstration that Mulder really isn’t that difficult to work with. His beliefs are far outside the mainstream, but the reality is that Mulder doesn’t make friends well. Mulder really is a jerk to the local law enforcement when they reveal they didn’t follow up one particular lead. “So basically you ignored her statement,” he bluntly states. He presses the issue when the sheriff argues he included it in the file. “But you didn’t bother to check it out.”

Outside, Scully astutely points out, “I just think it’s a good idea not to antagonise local law enforcement.” Rather than actually engaging with her criticism, or actually having a discussion, Mulder evades the point. “Who me?” he responds. “I’m Mr. Congeniality.” Mulder can easily come across as abrasive or confrontational. He can be funny and he’s definitely smart, but it’s hard to believe that Mulder’s personality would ever have allowed him to ascend the ranks of the FBI. This is very much consistent with the confrontational Mulder we met in Squeeze.

You are not alone… unless your family member has been kidnapped, in which case you are very much alone…

However, to the credit of writers Howard Gordon and Alex Gansa, Conduit is much more sympathetic to Mulder as a character, even as it acknowledges his flaws. His criticisms of the initial investigation are sound, but there’s more than that. He’s standing up for the kind of people who don’t have voices, and who don’t get heard because they simply fade out of view in the American system. The sheriff’s attempt to rationalise his lack of interest in Ruby’s disappearance is chilling.

“Let me tell you something,” the sheriff advises Mulder. “Darlene’s little girl was no prom queen. I can’t count the number of times I pulled her out of parked cars, or found her puking her guts out by the side of the road, it was just a matter of time before…” When Mulder prompts him, he continues, “Before something bad happened to her and if Darlene needs to make up crazy stories to get past that, fine. But don’t tell me to treat it as the truth, I not gonna waste my time.”

Quite simply, Ruby doesn’t seem to matter to the local law enforcement, and Mulder’s refusal to accept that illustrates something quite engaging about Mulder as a character. Perhaps due to his own loss, and his own experiences on the fringe, Mulder tends to be a lot more sympathetic to those people who tend to get ignored or overlooked by the system. Indeed, Mulder seems to respond to vulnerability. He snipes at Scully after she tells the NSA about Kevin, seeming genuinely frustrated.

“You shouldn’t have told them,” he protests. “They have no jurisdiction.” When Scully points out that they are NSA and that they think Kevin is a threat to national security, Mulder is dismissive. “C’mon, how could an eight year old boy, who can barely multiply, be a threat to national security? People call me paranoid.” One of the nice small scenes in the episode features Mulder with Kevin at the lake, protecting and holding the little boy – striking up a strange empathy with the child.

Mulder was always the more emotionally volatile of the leading characters. In The Strange Discourse of The X-Files: What it is, What it Does, and What is at Stake, Joe Bellon suggested the two lead characters in The X-Files represent a reversal of traditional gender roles:

For his part, Mulder no more signifies the traditional male cop than Scully signifies the traditional female. He is prone to strange moods, strong emotions, and light-hearted comments. Unlike more traditional male cop characters who flaunt a devil-may-care attitude as a kind of macho display, however, Mulder represents the emotional and empathic balance to Scully’s logical and rationality. He cries over the abduction of his sister when he was a child (‘Conduit’), he empathizes with families who lose their children, and he is obsessed with truth.

I’ve remarked quite a bit about how The Silence of the Lambs was a massive influence on The X-Files, in particular the portrayal of Scully. Indeed, those parallels were apparent from literally the moment Scully first appeared and would become more obvious in episodes like Beyond the Sea.

If an emotionally distraught FBI agent fires his gun in the woods, and nobody else is around… is it a felony?

However, it’s worth noting that The Silence of the Lambs isn’t the only Thomas Harris novel to serve as an obvious influence on Chris Carter. Scully is very clearly modelled on Clarice Starling, right down to her red hair and her background in forensic sciences. In contrast, Mulder is clearly very heavily based on Will Graham, the protagonist of Thomas Harris’ first book, Red Dragon. Red Dragon has been a massive influence on the portrayal of serial killers in fiction and the procedural subgenre.

The comparisons between Mulder and Graham are obvious. Both are obviously FBI agents, with a background in criminal profiling – specifically, serial killers. Both are regarded as slightly weird and creepy by their co-workers. Mulder is dismissed for his alien conspiracy theories, while Graham makes people uncomfortable in conversation by adopting accents and mannerisms unconsciously. Both end up as outsiders within the FBI. Graham had a mental breakdown and retired, while Mulder was exiled to the basement.

However, it’s also worth noting that author Thomas Harris shares Carter’s fun in reversing gender roles. Clarice Starling helped create a new type of female horror protagonist, embodied by Scully. Will Graham arguably embodied the same feminine traits suggested above, and Red Dragon climaxes with Harris putting Graham in the role of “damsel in distress”, to be saved by his wife. Interestingly, this reversal was absent from Michael Mann’s adaptation Manhunter:

The Thomas Harris novel and Michael Mann film diverge at this point. Mann depicts Graham as the traditional male hero, crashing through a picture window to save the life of the blind woman who had become Dolarhyde’s lover. In the book, Francis stages his own death for her benefit, then unexpectedly ambushes his adversary at Graham’s Florida Keys home (led there by an address sent by Hannibal Lecter). Graham would have died but for his wife, who hooks Dolarhyde with a massive Rapala lure and then blows the intruder away with a handgun. Mann’s macho ideology, and traditional Hollywood conventions, apparently would not permit such a gender reversal.

Much like Beyond the Sea acknowledges the influence of The Silence of the Lambs on the creation of Scully, the show would structure a later episode making the comparisons between Mulder and Graham more apparent. Paper Hearts, a superb episode from the show’s fourth year, would acknowledge Mulder’s profiling past by pitting him against a psychopath played by Tom Noonan, who also played the psychopath in Manhunter.

Conduit acknowledges that Mulder lacks objective distance from the case. When he finds a grave, he digs frantically. Scully points out that he is compromising a crime scene, but Mulder isn’t interested. “What if it’s her?” he asks. “I need to know.” Not her family, not the authorities. Mulder needs to know. When Ruby returns, Mulder tries to convince her mother to let her talk. “She should be encouraged to tell her story, not to keep it inside,” he tells the mother of the lost girl. “It’s important that you let her.” Darlene replies, pointedly, “Important to who?” Mulder wears his heart on his sleeve so obviously that even the guest cast can spot it.

Alex Gansa and Howard Gordon also acknowledge the flipside to Mulder’s system of belief. It all hinges on Samantha. His devotion to the truth as an absolute concept, his need to hold the government to account, his desire to unravel the tapestry of lies… it all stems from the loss of Samantha. This raises a number of interesting questions about who Mulder is and what he believes. He casts himself as a righteous crusader, but it isn’t quite that easy.

If Samantha came home, would Mulder keep on searching for answers? Would he still search out the conspiracy? Or would he simply put it all behind him and move on with his life – picking up where he left off all those years ago? We’d like to believe the former, to cast Mulder as a romantic hero with a worthy cause, but that seems a little too convenient – a little too easy to believe. Darlene is content to give up her pursuit of greater knowledge when her daughter returns home.

“Listen to me,” she advises Mulder. “All of my life I have been ridiculed, for speaking my mind.” The words resonate with Mulder, who responds, “But it was the truth, Darlene.” It’s a romantic sentiment, but perhaps that’s just Mulder deluding himself. Darlene got her daughter back. The truth doesn’t matter after that. “The truth has caused me nothing but heartache, I don’t want the same thing for her.” It’s an interesting and bold way to look at Mulder, but it feels honest. If Samantha did come home, if his faith were satiated, would he still strive for the truth?

Conduit is a solid episode of The X-Files, working best as a character-driven hour. The show works best as set-up, providing character background and motivation that would pay off dividends over the rest of the show. We don’t really learn anything we didn’t already know, and it’s clear that Carter was already rationing the flow of information about the alien conspiracy at the heart of the series, even this early in the game. The first season generally moves the conspiracy arc along at a decent pace, so the holding pattern here isn’t as frustrating as it might be.

Once again, The X-Files demonstrates that it has its finger on the pulse of nineties pop culture. “It’s coming from there,” Kevin boasts, pointing to the static on the television – a sequence that can’t help but evoke Poltergeist. Poltergeist was, of course, produced by Steven Spielberg, who remains a massive influence on the show. Echoing Close Encounters of the Third Kind, our leads discover music buried in the code that Kevin is transcribing – the Brandenberg Concerto, “just fragments, a few notes here, a few notes there.” A sample played briefly recalls the famous five-note welcome from Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Conduit isn’t the strongest episode of the first season of The X-Files, but it continues a strong run so far. It’s clever and insightful television. The plot is functional and perhaps a little too structured at times. I think that The X-Files can be seen as an evolutionary link between The Silence of the Lambs and the crime procedurals of the twenty-first century, and you can really see that here. Aside from the subject matter, Conduit actually has a rather significant overlap in format with CSI or Criminal Minds, although I’d argue The X-Files used that format much more creatively, and with greater purpose.

Still, the best part of Conduit is the way that it shines a light on Mulder as a character, and sets up years of character development to come.

You might be interested in our other reviews of the first season of The X-Files:

- The Pilot

- Deep Throat

- Squeeze

- Conduit

- The Jersey Devil

- Shadows

- Ghost in the Machine

- Ice

- Space

- Fallen Angel

- Eve

- Fire

- Beyond the Sea

- Gender Bender

- Lazarus

- Young at Heart

- E.B.E.

- Miracle Man

- Shapes

- Darkness Falls

- Tooms

- Born Again

- Roland

- The Erlenmeyer Flask

Filed under: The X-Files | Tagged: chris carter, Christian Right, Cold War, Dana Scully, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Fox Mulder, gillian anderson, Gulf War, IDW Publishing, mulder, Mulder & Scully, scully, United States, world war ii, x-files |

As a pivotal part of my late teens(I was 16 in 1997 when I started watching it), I am really looking forward to watching this movie. Thanks for this awesome review!

Yep, I grew up with The X-Files as well.