To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the longest-running science-fiction show in the world, I’ll be taking weekly looks at some of my own personal favourite stories and arcs, from the old and new series, with a view to encapsulating the sublime, the clever and the fiendishly odd of the BBC’s Doctor Who.

Logopolis originally aired in 1981. It was the second instalment in the “Master” trilogy.

It’s the end… but the moment has been prepared for.

– the Doctor finally figures out what this year has been about

I don’t think the departure of a Doctor has even been a bigger deal than it was with Tom Baker. Sure, Christopher Eccleston’s first season was so fixated on death that his departure seemed preordained, even in the episodes written before his decision to leave. Similarly, Peter Davison’s final year seems designed to demonstrate that the universe is no longer suited to this particular iteration of the Doctor. Maybe David Tennant’s final year is focused on his passing, but the episodes are so spaced out that it makes little difference. However, we’ve just spent an entire year focused on the idea of entropy and decay, the inevitably of change and the notion that death is just a nature part of the cycle of things.

When the Doctor assures his companions that “the moment has been prepared for”, he may as well be looking at the camera, assuring those of us at home that the past year has been spent readying them for the unthinkable: the time when Tom Baker might not be the Doctor.

To an entire generation, Tom Baker is still the Doctor. Sure, there might be Christopher Eccleston, David Tennant or Matt Smith running around, but they are just pretenders to the throne. There’s a reason that Baker’s iteration of the character is the one that tends to turn up when popular culture wants to make reference to Doctor Who. For seven years the actor anchored the show, through several radical tonal shifts and different eras, something of a fixture in the British television landscape. The notion that Baker might depart the role must have seemed quite daunting.

Indeed, Baker’s shadow was so incredibly overwhelming that producer John Nathan-Turner reportedly even instructed director Peter Grimwade to shoot the regeneration scene in such a way that the following season could open without a shot of Baker regenerating into Davison:

For Logopolis, John Nathan-Turner wanted a good transformation which would show the full changeover from Tom Baker to Peter Davison and so not make it necessary to repeat the scene for the first story of the next season. It was intended that Logopolis should show the full change.

The departure of Baker must have seemed to represent the decay and corruption of the entire world of Doctor Who. It seems, in Logopolis, that the very universe is falling apart in manners both big and small, as the Fourth Doctor’s time grows nearer and nearer.

Writer Lawrence Miles has argued that Logopolis might be his favourite adventure “because it’s supposed to be the Fourth Doctor’s funeral, and it feels like a funeral.” He’s certainly right on that point, and the best part of Logopolis is the sense of impending doom that it creates, building successfully off the superb atmosphere in The Keeper of Traken. You can practically feel the grim reaper sneaking up behind the Doctor as the adventure progresses, and it seems that he has no real chance of escape.

Which, to be honest, leads to my biggest problem with the episode. The death seems somewhat arbitrary. That’s not to suggest that death is always big and meaningful on Doctor Who – just ask Colin Baker and Sylvester McCoy (and Paul McGann) about that. However, Logopolis goes out of its way to repeatedly tell us how epic this moment is, how momentous and how well-planned and how inevitable it all is…

… and then the Doctor falls off a satellite.

Sure, he falls off a satellite saving the universe or something, but the stakes aren’t what makes a death memorable. The Fifth Doctor would die saving one life in a story preoccupied with death. It’s nice to go out saving the entire universe, but just saving the entire universe doesn’t make the death that memorable. There needs to be something more – something heavier, something more inherently heroic about it.

It might be okay for the Doctor to die by random chance, but not if you’ve spent an entire year building to this one moment. Not if you have a mummified almost divine future iteration of himself supervising the damn thing. Dropping Tom Baker off a satellite dish recalls the decision to kill Captain Kirk by dropping a bridge on top of him. It is a moment that has been hyped and built up… and then completely misfires.

Part of this is undoubtedly the technical limitations of the time. I’m a bit disappointed the restoration team didn’t consider revisiting the “death” sequence. The walkway the Doctor navigates is obviously entirely inside a studio, but that’s not the problem. The problem is the pixelated background image of the Master inserted at ridiculously low resolution onto a CSO screen to create the impression he is watching his nemesis die. There’s a shot of the Doctor dangling where it’s quite clear he’s a doll – maybe the same doll used in the car.

I talked about this last week, but one of the many drawbacks of Christopher Bidmead’s relatively serious approach to Doctor Who is that the attempt to play it entirely serious is undermined by the dodgy special effects. Douglas Adams and Graham Williams could get the audience to forgive a lot with a knowing smile or a cheerful wink, but playing everything entirely straight makes it harder to get past these problems.

Even if you can get past the dodgy execution of the big moment, the entire sequence runs a little weird. I get that the Watcher is apparently the Doctor, but why is he here? Why is he present for this regeneration, particularly when it seems especially ridiculous. It’s hardly as if the Doctor had a moment where he had to decide to take a bigger risk than he has ever taken before. He doesn’t know that his trip out to the catwalk will end in his death. It isn’t a heroic sacrifice.

It’s just a random death trap that worked – something which seems inevitable when you assume the laws of probability, but unlikely given the rules of narrative. That’s why it feels so anti-climactic. We’ve spent so long building to the moment, and it’s just the kind of thing he’s done countless times before. The ropey special effects don’t help, but they are very far from the only problem with that sequence.

Speaking of Bidmead’s style, it also makes some of the cheesy plot points that you expect in Doctor Who seem weirdly out of place. Bidmead concedes that Adams accused him of including “cod” scenes like the Master holding the universe to ransom, and it’s a fair criticism. The Master turning people into dolls, holding the whole universe to ransom and acting nuttier than squirrel excrement feels world’s away from the sensible way that he was portrayed in The Deadly Assassin and The Keeper of Traken.

It also draws to attention the camp and absurd nature of Doctor Who which feels out of place in Bidmead’s quite rational version of the show. Indeed, the entire scheme here feels quite out of place with virtually everything else this season. (Well, apart from maybe Meglos.) The Master plans to hold the universe to ransom by “generating entropy” – I’m not a physicist, but I’m fairly certain that entropy doesn’t work that way. It’s a nice high-concept, the use of entropy to motivate the plot, but let’s not pretend that it’s anything approaching scientifically credible.

That said, again, it works well thematically. Entropy has been a none-too-subtle theme for the year. As the Doctor explains, “The more you put things together, the more they keep falling apart, and that’s the essence of the second law of thermodynamics and I never heard a truer word spoken.” The death of the Fourth Doctor is the ultimate inevitable sign of decay, worn down as he is by a tough year, and Logopolis effectively features a grim silence falling over the universe, almost a moment of silence in respect for the character.

On the other hand, despite the massive stakes involved in this regeneration, which should logically increase the dramatic tension, the episode fails to capitalise on the fact that the Master is essentially responsible for wiping out a huge portion of the universe. This would make it the most successful of the Master’s plots, but Logopolis immediately undoes all the good work that The Keeper of Traken did when it revived the character. He’s more dangerous than ever… but only accidentally.

The Master causes a death toll that is almost unfathomable, but Logopolis doesn’t allow him to do so intentionally. Instead, it happens because of a cock-up. Not only does the story make him look insane, it makes him look incompetent. What’s really weird, though, is that the script seems to conspire to avoid making all these deaths the Master’s fault, despite the fact that he’s already a complete monster to us. There’s nothing to salvage by declining to show him as a mass-murdering psychopath, because all that does is extrapolate from what we already know of the character.

He’s been back for one adventure and they have already messed him up. He has been tied into the origins of both Nyssa and Tegan in fairly important ways. “The Master killed my stepmother,” Nyssa explains, “and then my father, and now the world that I grew up in, blotted out forever.” He also murdered Tegan’s aunt. Although I’m not sure the Doctor ever lets Tegan know that. He just makes a cheap pun about the fact that a mad man turned her into a doll. Asked had he seen her, the Doctor replies, “A little of her.” He then whisks her away.

In theory, the Master should be a more potent threat than ever, his tendency to turn people into dolls notwithstanding. He has killed a significant portion of the universe. He has a strong personal connection to both female companions. In theory, he should be in a strong position going into the Davison era. Instead, unfortunately, the show bungles both. His mass murder makes him look incompetent rather than fiendish, and the connections to Nyssa and Tegan are never addressed. And yet the show still found a way to weaken the character further in Castrovalva.

Which brings us to Tegan. Normally I like strong female companions on the show, and Tegan remains relatively popular with fandom. So I should love Tegan, right? Part of me thinks that I would, if she remained a Tom Baker companion. A lot of Doctors – like Pertwee, Baker or Tennant – worked best with companions who were willing to stand up and challenge them. I actually think that Tegan would have worked much better with Colin Baker than Peter Davison. (Yes, I do think Nicola Bryant would have worked better with Peter Davison, why do you ask?)

The problem is that Davison spends so many of his stories lurking around in the background that the last thing he needs is a forceful loud-mouthed aggressive companion. Nyssa is much more of a conventional sort of companion, but I think that Davison and Sutton worked well together. I think the first half of Davison’s tenure is weighed down by the fact that he has Adric and Tegan on board. Tegan gets better with time, mellowing and moving out of the choir and into the spotlight. Turlough works surprisingly well with Davison.

I’m apparently not alone in feeling this way. Discussing his companions, Davison confesses:

I liked the character of Nyssa best of all. She seemed to me to work best in the Doctor Who format. Now I know that she wasn’t as popular a character as Tegan, but speaking from the Doctor’s angle, I don’t think that stroppy type works as well as the more passive, ‘pass the test tube’ kind of assistant. I think if you try and break the mould then the character emphasis changes and you’re veering dangerously into the realms of soap opera. I really like that kind of gentle character that Nyssa had – it was a good contrast, and I think that she went best with the Doctor I played. That’s not to pass any kind of judgement on Janet Fielding or Mark Strickson or anyone, because we all got on tremendously well. It’s just an opinion about the characters.

I know I should like Tegan’s willingness to stand up to the Doctor and her ability to question him, but the Fifth Doctor is very much an atypical iteration of the character, and so the general rules don’t apply.

There is something that Tegan does here, though, that is very interesting. The last couple of years have seen the Fourth Doctor growing increasingly distant from Earth. Sure, there’s the occasional trip here like in City of Death or at the bookends of The Leisure Hive, but the Doctor has drifted away. Since the departure of Sarah Jane, his trips to Earth steadily decreased. He paired up with a Timelady and robot dog, and picked up an alien stowaway who wasn’t even from out universe.

Given all his time away, it’s remarkable that Logopolis spends so much time on Earth and it’s refreshing to hear him refer to it as his “home away from home.” The story starts and ends there, appropriately enough like the Fourth Doctor’s tenure. Tegan is the first human character since Sarah Jane and – as such – she serves to anchor the series on Earth. A great deal of the following season would be spent trying to get Tegan back to her time and place, obviously involving lots of trips to Earth at various points in its history. It feels appropriate. Davison was arguably the most human of Doctors until Christopher Eccleston took the role.

So, if I don’t like the regeneration, I don’t like the Master, and I don’t like the regeneration, what do I like? Quite a lot actually. Pretty much everything else, which makes those significant problems all the more frustrating. The death of the Doctor is a big event. The death of the Fourth Doctor feels like the end of the universe. While the death of a significant portion of the universe by entropy doesn’t resonate as well as it should, Logopolis does an exceptional job creating the sense that something is very wrong.

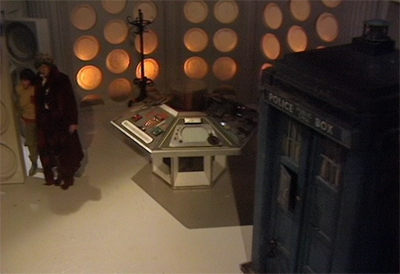

Everything is falling apart. Even the TARDIS. When we find the Doctor pacing, the place looks like it is decayed and overgrown. The entire plot is driven by the fact that the Doctor needs to repair the TARDIS. “The second law of thermodynamics is taking its toll on the old thing,” he explains to Adric. “Entropy increases.” The TARDIS is sick, and we hear the cloister bell for the first time. The Doctor’s ship seems to be crying.

The Doctor suggests fixing the chameleon circuit, which seems logical if you’re talking about a piece of technology, but would be a radical change for the show itself. Lose Tom Baker and lose the iconic blue box? That really would be the death of the show, and it’s very clear that Bidmead’s smart script is playing with that idea. It isn’t just the Doctor getting old, it isn’t just the TARDIS breaking down, it isn’t just the universe collapsing around him. The very narrative itself, the glue that binds Doctor Who together, is coming apart at the seams.

The show opens with a police man using a police box, which stands out as one of the most surreal images in the show’s history. It’s a wonderful bizarre idea: that the ordinary use of an ordinary object should seem so strange. We’ve become so conditioned to the TARDIS that seeing the police box as a police box feels somehow weird. It’s a TARDIS with the magic taken out. It’s no longer bigger on the inside.

And then, almost immediately, we see the blue box – one of the most iconic aspects of the series, the one constant that has outlasted any actor – eat a man alive. That turns everything we know upside down. It’s still unsettling even today, to see the police man taken inside the blue box as if it is swallowing him whole. (Of course, the Master turns him into a silly doll, but we don’t know that yet – even if the evil laughter is a bit of a hint.)

As the death of the Fourth Doctor approaches, the laws of Doctor Who break down. In another small scene which feels strangely disturbing, the Fourth Doctor finds himself unable to bluff his way past law enforcement officials. It’s a scene we know very well. The Doctor meets an authority figure, and either outwits them or convinces them he means well. However, Logopolis defies this convention, as Baker’s Doctor finds himself just a little bit trapped.

Examining the remains of the Master’s victims, he finds the situation slipping out of control, despite his bluster:

Well, I do have opinions. This is the calling card of the most evil genius in the universe and I have to tell you gentlemen, I’ve got to get after him. Now, if you’ll just help me to create a diversion, hmm?

I think you’d just better come along to the station with us, sir.

I’d love to.

Just to assist us in our enquiries.

Would you mind awfully if I stopped to telephone my solicitor?

You can do that back at the station.

It seems we’re going to be awfully busy at this station of yours…

Yes.

… I mean, isn’t that a telephone box?

That’s a police box, sir, not for —

But that would do fine, don’t you agree?

Look, sir, if you want a formal arrest?

Er, no.

It’s subtle, but it’s clear the Doctor is losing control of the situation. Two people have been murdered, and the narrative tropes that would allow him to usurp authority are not kicking in. The cops act like they’ve just found a rambling crazy man on the side of the motor way, not the greatest hero in the universe. They even almost get him into the back of the car, and his escape seems especially desperate.

And then there’s the fact that the TARDIS materialises inside itself. That’s one of the very few things we’ve conditioned to accept as absolutely impossible on this show. Everything is literally inside out. It’s a great concept, even if it does turn out to be the Master’s TARDIS. Although Steven Moffat would execute a purer variant the same idea for charity specials during his tenure. Still, it’s a great visual, and a sign of how the laws of physics and the laws of Doctor Who are all being breached. It does a great job of creating a sense of collapse that really compounds the sense that there is something very wrong.

Incidentally, there’s a whole host of “timey wimey” stuff implied in this episode, even if it’s never outright stated. For example, how did the Master know the Doctor would pick that police box, unless he used time travel? More than that, though, there’ the question of Nyssa. In the novel Asylum, it was revealed that the Doctor knew Nyssa would be a companion of his successor. As such, did the decision to leave her on Traken (well, not to invite her) stem from his knowledge that her arrival would herald her death?

It would explain why the Watcher brought her, and – perhaps – imply the reason that the Watcher exists. Based on what we see here, I think you could argue that the Fourth Doctor did not want to die. He spends a lot of time here procrastinating. He refuses to return to Gallifrey to face the inevitable, advising Adric, “I think that you and I should let a few oceans flow under a few bridges before we head back home.”

If the Fourth Doctor was actively resisting his fate, was the Watcher some transcendental potential version of himself trying to get time back on course? That would explain why he brought Nyssa to Logopolis, as it certainly wasn’t to allow her to interact with her father, who she seems to get over rather quickly. It might also explain why the Watcher talked to the Fourth Doctor, even if we didn’t see their conversation. If the Tenth Doctor had tried to refuse his own fate, would something similar have happened?

There’s some nice character stuff. It is nice to see the Doctor miss a companion for more than five minutes, as he reflects on the loss of Romana back in Warriors’ Gate. Discussing the TARDIS with Adric, he confirms that he had planned to travel quite a while with her. “According to the handbook, yeah, because the outer plasmic shell of a Tardis is driven by the chameleon circuit, or so the theory runs,” he admits. Then he states in a “we’d get around to it eventually” sort of way, “In practice I always meant to ask Romana to help me fix it one day.”

It’s clear that the Doctor thought he’d have longer with her. I honestly think there’s a reading here that suggests the Doctor was completely in love with Romana, in a way that he wasn’t with any other companion. Indeed, he even visits her now-empty room. It still has her stuff, a sign of how quickly she left. Which is nice, because her departure in Warriors’ Gate was rather abrupt, so it’s nice to see the show acknowledge she effectively abandoned her home without packing a bag.

It’s also quite clear that Romana was special, long before fans kicked up a fuss about how odd it was to see the Tenth Doctor missing Rose. It is (quite pointedly) Romana that he misses, not K-9. “Ah,” the Doctor remarks to young Adric. “I suppose we’re going to miss Romana.” Adric has to gently remind his fellow traveller that Romana was not the only supporting cast member to leave recently. “And K-9, too,” he prompts.

Quite touchingly, Logopolis forces the Doctor to confront the fact that Romana is gone before he faces his own mortality. As he tries to leave Earth, he finds the TARDIS is weighed down. “Adric,” he explains, “I’m going to jettison Romana’s room.” It really is one last goodbye, and Romana casts a shadow over this story in a way that no departed companion in the classic series ever weighed on the Doctor’s mind. I like it a great deal, as it plays into the season’s themes about loss and change.

And then there’s Logopolis itself. Of course, it’s let down by the production values of the time, looking like a bunch of cardboard boxes all lined up against a model of a satellite dish. The notion that the most advanced mathematical culture in the universe would steal satellite designs from humanity does seem a little absurd as well. Still, as a concept, it works surprisingly well, offering us something a bit different than usual.

I remarked in my discussion of The Keeper of Traken that despite Bidmead’s preference for hard science fiction, his shows worked best when they balanced science-fiction with fairy tales. The Keeper of Traken presented a world based around science where evil would petrify on contact, built around a distinctly religious culture. Logopolis offers us something similar. It’s a society that fights entropy using advanced mathematics to influence the very fabric of the universe.

More than that, though, their calculations sound almost like a form of ritualised prayer. They chant and keep rhythm, and their beliefs can shape the world itself. “Our manipulation of numbers directly changes the physical world,” the Monitor explains. “There is no other mathematics like ours.” It’s fascinating how Bidmead often finds a way to integrate science and religion, rather than setting them at odds with one another.

The idea of “block transfer calculation” is also a fascinating high concept, the idea of maths that cannot be done by machine, and which requires an organic brain to properly formulate and express it. “Block transfer computation is a complex discipline, way beyond the capabilities of simple machines. It requires all the subtleties of the living mind.” It is absolutely fascinating, and an idea that feels worthy of a whole four-part serial.

It feels a bit of a shame to shove the idea into the back end of this adventure, but Bidmead does the same thing in Castrovalva. There the concept of the weird city is contained primarily in the final two episodes of the serial, which is actually a pretty neat structural idea, given how Davison’s first year was broadcast. And, to be honest, it is better to be left wanting more of a concept than to think that it has been overused.

There’s a lot in Logopolis that I like, but I will confess that I find it quite disappointing. The Keeper of Traken managed a deft job balancing the unforgiving producer edicts and introducing its own clever elements. Logopolis does an exceptional job with its own high concepts, but it struggles a bit with the obligations that come with being the last Tom Baker story. The Master doesn’t come out looking well, the new companion feels like she overburdens the script, and the Doctor’s final scene is anti-climactic.

Still, despite that, I can’t quite hate it. There’s too much good stuff here for flaws as big as those to completely sour me on the story. Instead, it remains a story that could – and should – have been a whole lot better than it was. Still, it is ambitious and clever, and those attributes are hard to condemn.

Filed under: Television | Tagged: arts, bbc, christopher eccleston, Colin Baker, doctor, doctor who, DoctorWho, fiction, Fourth Doctor, Janet Fielding, John Nathan Turner, Keeper of Traken, Logopolis, Master, paul mcgann, Peter Davison, Romana, science fiction, Sylvester McCoy, Tom Baker |

Tegan did know the master killed her aunt. And the master revels in having the power to save the universe, so what if it started accidently. This is a flawed story but still a great end to the Season and to baker’s era.

Thanks for that Martin. I don’t think I was too harsh on the story, to be fair.

Entropy and the heat death of the universe really, really, really do not work the way they are described in this episode. But then, blatant misuse of scientific terms to create a threat in science fiction was widespread in that era, and more recent stories even sometimes fall victim to it. However, it would have been much better had they just made up something for Logopolis to be protecting the universe from.

Other than that being enough to pull some of us right out of the story all on its own, the big threat to the universe is barely shown. Half the universe or whatever is wiped out in five seconds by a line of dialogue and a graphic on a viewscreen, and even Nyssa barely cares. It was done so casually I was certain the destruction would be undone by whatever technobabble was used to save the day in the end. Meanwhile it’s a bright and sunny day on Earth throughout.

Combine that with the Doctor dying of something that in any other episode he would have survived simply by holding on better, and the entire ending is a huge anti-climax. It feels like, and was, an episode whose sole reason for being was to bring in the new Doctor, two new companions, and the new Master.

The story problems are even personified in the form of the Watcher, who exists for the sole purpose of filling plot holes like ferrying characters through time when the Doctor is unavailable and telling characters what they are supposed to do next.

Surely this episode was a huge let-down to anybody who’d been watching for all seven years of Baker’s tenure as the Doctor.

Those are all fair and valid points. It’s certainly not the strongest regeneration episode. (Caves of Androzani or The Parting of The Ways for me, but The Time of the Doctor has also grown on me.)

But I like the lyrical metaphorical quality to it, even if – as you point out – those touches make little-to-no sense and are incredibly arbitrary. But I like the weirdness of it all, and the sense of fatigue that runs consistently through the season as a whole.