To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the longest-running science-fiction show in the world, I’ll be taking weekly looks at some of my own personal favourite stories and arcs, from the old and new series, with a view to encapsulating the sublime, the clever and the fiendishly odd of the BBC’s Doctor Who.

The Keeper of Traken originally aired in 1981. It was the first instalment in the “Master” trilogy.

He dies, Doctor. The Keeper dies!

– Tremas heralds the end of an era

Of course, the entire season has been less than subtle about the point, but The Keeper of Traken is the point at which Tom Baker’s final season builds to critical mass, and reaches the point of no return. Entropy, decay and death have all been crucial ingredients in the year’s collection of adventures, but The Keeper of Traken is the point at which it seems like our character has set himself on an incontrovertible course, a path from which he cannot diverge. Baker’s approaching departure gives The Keeper of Traken a great deal of weight, and helps balance a story that might otherwise seem excessive or overblown. There’s melodrama here, but it feels strangely appropriate.

Lawrence Miles has argued that Logopolis was the funeral for the Fourth Doctor. If so, The Keeper of Traken is his wake – and it’s fitting that Irish poet and writer Johnny Byrne should provide this strangely lively (if morbid) celebration.

Part of what’s impressive about The Keeper of Traken is how well it does the things that it was never really intended to do. There are plenty of stories in the history of Doctor Who that have been ruined by alterations made to the script to make it fit a particular mould or style, and it’s a testament to writer Johnny Byrne and script editor Christopher H. Bidmead that the serial doesn’t collapse under the weight of having to hit these larger narrative plot points.

For example, the show introduces Nyssa, who will join the TARDIS in the next adventure, Logopolis. Indeed, Nyssa wasn’t originally intended to be a companion, with Sarah Sutton conceding that it was “a little while” before the production team asked her to become a regular. Similarly, the Master was shoehorned into the episode at the last minute, replacing an original villain named Mogen. Apparently, with Baker’s departure looming, John Nathan-Turner had sought to bring back a familiar face, and – after failing to convince some companions to return – he decided to revive the Master.

It’s easy to imagine these editorial demands weighing The Keeper of Traken down a bit. To be fair, Nyssa’s increased involvement over the length of the serial does seem a little out of left field, but it’s not too problematic. After all, there have been worse introductions for companions than saving the Doctor from a dungeon. It’s funny that Nyssa was a last minute addition to the TARDIS crew. Peter Darvill-Evans’ novel Asylum, written in 2001, suggests that the Fourth Doctor met an older Nyssa before this story, and thus learned that she was to be one of his companions.

I don’t want to dwell too much on the supplementary material, but I do love that twist, and how it so cleverly sets the behind-the-scenes reality against fan-created continuity. Despite the fact that the production history indicates she was a last-minute companion, the expanded universe makes her practically preordained. It’s a beautiful juxtaposition, and I’m actually a big fan of Nyssa as a character. Despite my preference for more proactive female companions, I actually prefer Nyssa to Tegan – if only because she works a lot better with Peter Davison.

The other narrative obligation imposed on The Keeper of Traken is to reintroduce the Master, and the script does this quite cleverly. So cleverly, in fact, that The Keeper of Traken ranks among my very favourite stories featuring the character. (That said, it is arguably a very short list.) It’s also worth noting that -despite being another late admission – the script treats the Master as a character rather than an easy, cheesy cliffhanger.

Compare the reveal of the long-absent Master here to the appearance of the longer-absent Cybermen in Earthshock. The Cybermen reveal is positioned at a cliffhanger, somewhat awkwardly – and in a way that doesn’t necessarily make sense to people unfamiliar with the aliens for Doctor Who. Here, we see the Master long before he’s identified, and there’s enough clues scattered throughout the episode to lead even the novice audience member to the fact that another Timelord is tinkering with Traken.

There’s the sound that the Melkur makes as it disappears. There’s the set design inside the Melkur. There’s the simple fact that it is larger on the inside than it really could be. Indeed, the reveal of the Master’s face – clearly meant to be the same scarred visage from The Deadly Assassin – it’s never treated as a BIG moment. His name isn’t revealed along with his face. The focus is on the fact that he looks like some grim reaper, not that he’s an obscure villain who hasn’t appeared in years.

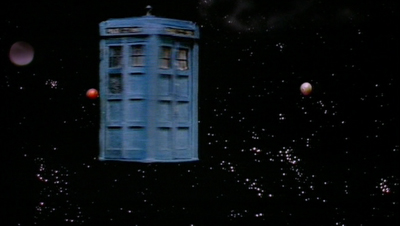

When Tom Baker arrives in the black TARDIS and actually calls him “Master”, the how doesn’t milk it for cheap thrills. I’d argue that one of the problems with the later years of the show was that sense of nostalgia, that the show owed its older fans continuity or inside jokes. This often led to clunky plots (like Attack of the Cybermen) and – when it didn’t – it still created the impression that viewers were being “locked out” of the show. It’s never a good idea to lock viewers out, and I’ve praised Russell T. Davies for making the revival so accessible.

And The Keeper of Traken is accessible. If you know the Master, that’s great. There’s some lovely stuff here about him, and some nice character beats that I quite like – something that we didn’t see often enough in Roger Delgado’s wonderfully flamboyant performance, and which would disappear with Anthony Ainley’s increasingly pantomime villainy. However, if you’ve never heard the name “Master” before, then The Keeper of Traken tells you everything you need to know about him. And quite efficiently, too.

More than that, though, the serial picks up from The Deadly Assassin in that it gives the Master some credible motivation that doesn’t have to be inferred as some sort of mental disorder. He wants control of Traken, to exploit the chaos of the death of the Keeper in the same way that he exploits the death of the Doctor. His own decay and degeneration, though carried over from his previous appearance, also serves as an effective mirror to the Doctor’s looming demise.

It also provides a nice way of revisiting the Timelord regenerative cycle. While the Master is now an abherration, his involvement allows for reasonably comfortable exposition to clue in any new or casual viewers on a process that (barring an awkward joke intro in Destiny of the Daleks) hasn’t occurred in the last seven years. A lot of the show’s clumsy exposition can be explained by virtue of the fact that it came from a time before VHS, but The Keeper of Traken provides a masterful example of an audience refresher that works well.

Not only do have confirmation that – for a regular Timelord at least – death isn’t the end, but we also get the finite number of regenerations from The Deadly Assassin handily restated. It’s a nice way of both reassuring the audience that the show will continue without Tom Baker (which must have seemed a little uncertain at the time) and also raising the stakes (a single life isn’t the be-all and end-all, but the counter is also ticking down in a slower manner too). Bidmead might have his flaws as a script editor – we’ll come to those – but the struturing of this would-be stand-alone tale as the first in a loose trilogy is quite brilliant.

Now then, back to the Master. Whereas we can infer various reasons why the Master repeatedly refused to kill the Doctor whenever he got the chance, at least we have a motivation here that makes sense. The Master is dying. He – understandably – does not want that to happen. Death is terrifying for anybody, but at least some part of us knows it is inevitable. Now imagine the feeling if you’re functionally immortal, or damn close to it at any rate. Imagine discovering, having lived millenia, that you were likely mere years away from death at most. Also imagine you’re a selfish egomaniac who wasted a lot of your time attacking the one planet housing the one person who could stop you.

There Master does conspire to keep the Doctor alive for most of The Keeper of Traken, but it makes more sense here than usual. He’s dying, so his inferiority complex and need for acceptance don’t cut it – not that they were the strongest or most rational motivators to begin with. No, the Master wants something practical. It is quite clear that he wants to claim the Doctor in the same way that he eventually had to settle for Tremas. Preparing to clutch the Doctor, he observes, “With my new powers, anything is possible.” Given that Logopolis reveals that the Keeper’s powers allowed him to bodyhop to Tremas, the implication is logical and in-character.

And yet, despite that, he’s not a moron – which is probably why I am so fond of him here. Even tempted with the prospect of the Doctor’s remaining regenerations, he’s less of a genre-blind idiot than he normally seems. When Kassia comes to him for advice after the Doctor has been messing around, he doesn’t hesitate. There’s no mention of his “game” or his “fun.” This is business, much like his mad dash up the satellite in Terror of the Autons. “First, the Doctor. It is clear now he must be destroyed.”

Indeed, the Master seems like a character here, rather than a broad archetype or pantomime villain. His contempt for the Doctor’s ability to endure seems palpable, as he sheds the mask of affability he is fond of wearing. “Doctor. So you survive after all.” There’s also a dash or two of his gigantic pride to found, even as he is on the verge of death and more dangerous and desperate than before. I adore the ridiculously camp way he manuevers his TARDIS in the form of a Melkur (because, really, it’s like parking your Ferrari on a throne), but also the way he seems a little stung the Doctor doesn’t recognise him.

All that and the script finds room to play with the the rather obvious undertones in the relationship between the pair. Lording his power over the Doctor, the Master boasts, “The knowledge will be taken from you atom by atom, and what is left of you, the husk of your body, that will also have its uses.” Even Russell T. Davies was sure to keep the homoerotic domination subtext a tiny bit more subtle than that. (He is, of course, talking about stealing the Doctor’s regenerations, but (a.) we don’t know that yet, and (b.) … c’mon.)

However, it’s a testament to The Keeper of Traken that it manages to be such a great Master story, even though the Master is very much a last minute addition to the plot. The Nathan-Turner era of the show runs for eleven years, and I think it’s fair to argue that the producer’s tenure can be broken down by his script editor. The show as script edited by Eric Saward was radically different from that overseen by Andrew Cartmel. This final year of Tom Baker’s tenure was script edited by Christopher Bidmead.

You could argue that each regeneration of the Doctor can be read as a reaction against his predecessor. In Bidmead’s case, his term as script editor seems an especially conscious reaction against his predecessor in the position, Douglas Adams. I actually quite like both approaches to the series, but they couldn’t be further apart. Adams favoured a smirk and wink as he engaged the show’s camp tendencies. Bidmead, on the other hand, saw camp as something to be avoided.

I then had to confess to John and Barry Letts that I didn’t actually want to do Doctor Who, as it had got very silly and I hated the show. They agreed with me – Barry wanted to go back to earlier principals and to find a way of familiarising children with the ways of science. You can understand how deeply that idea had been subverted.

Two things were going wrong. One was the pantomime element, and the other was the element of magic which had come in. Magic is entirely contrary to science and to my mind the Doctor’s view of the world is that he looks at a problem objectively and then tries to apply laws derived from experience to reach a scientific solution.

Bidmead very clearly has his own view of what Doctor Who should be, rooted in its past as an educational show. He also, it appears, seems to believe that it’s the only valid way to do the show – having been vocal in his criticism of his predecessors and his successors. (Indeed, he rather harshly dismissed The Doctor, The Widow & The Wardrobe as “Mary Poppins meets Enid Blyton meets CS Lewis.”)

Bidmead’s approach is fascinating, and it’s hard to deny that his work on the show is populated with fascinating high concepts. Full Circle, Warriors’ Gate and Logopolis are brimming with clever science-related ideas, as is his introduction to the next season, Castrovalva. That’s not to suggest that Douglas Adams didn’t have his share of brilliant ideas, but they were more often clever ways of integrating science-fiction concepts with bright ideas, as opposed to ideas rooted in science itself. (For example, City of Death features a brilliant scam – but it’s a fairly conventional scheme that just exploits time travel to work.)

This earnestness is both the greatest strength and the greatest weakness of Bidmead’s work on Doctor Who. At his best, his work seems a great deal more substantial due to the integration of these concepts. Bidmead’s fascination with science lends the show an interesting avenue to explore the universe in a way that it hadn’t really before. Bidmead continues the Williams’ trend of moving the Doctor away from Earth, but into a cosmos filling with things that don’t necessarily conform to our expectations of them.

It’s also refreshing to see the show taking itself relatively seriously. Doctor Who needs a certain amount of charm and wit to work as a concept, but the previous season had perhaps gone too far to the extreme. It also allowed Tom Baker and his skill for surreal comedy to dominate the show to an even greater extent than he had before. The result of reducing the indulgence in camp allowed the show to get back to bigger ideas, but it also loosened Tom Baker’s grip on the role.

While it’s impossible to imagine Peter Davison taking over the role following the Graham Williams’ era, this past year has seen the universe shift radically around the Fourth Doctor so the show is less driven by Baker’s wit and charm. Part of that is obviously down to the theme of entropy and decay giving us a year to get used to the idea that Tom Baker is departing, but at least some of that is down to the scripting itself.

However, Bidmead’s approach also has its flaws. Despite his earnestness, it is impossible to fully get rid of the camp in Doctor Who, and playing everything dead straight makes a lot harder to accept the cheesy special effects as part of the appeal. The fact that the Melkur’s eye lasers look like something from an early Nintendo game would be part of the charm in a Williams’ era episode. Here, they detract from what has been a fairly serious tale of palace intrigue, and their absurdity stands in contrast to the po-faced seriousness of it all.

It feels a bit unfair to mention that in discussing The Keeper of Traken, a story with production values that seem remarkably good. Of course, you’re never convinced that anywhere in the episode is outside (it’s obviously all a studio), but it is very well executed by all involved. Even the music is quite good, conspiring with the costumes and settings to evoke a medieval vibe. The special effects are a bit ropey, but that’s to be expected at this point in the show. Everything else is pretty great.

The problem is more fundamental than the special effects (although I would love to see a Bidmead script executed on a bigger budget), as Doctor Who has always been more science-fantasy than science-fiction, from the moment that the Daleks first appeared in The Daleks. It was those aliens that set the tone for what “science” means in Doctor Who, and Bidmead can’t escape that necessary ridiculous element. Bidmead might prefer relatively hard science, but the Master still uses mind control on Kassia through the process of “gentle irradiation” and the show still relies us to invest in a police box flying through space.

Indeed, The Keeper of Traken runs on a premise that is as fantastic as anything that Douglas Adams ever wrote. We’re told that the Traken Union is “famous for its universal harmony” and is held together “by people just being terrible nice to each other.” There’s nothing too irrational about that. However, as we discover, this isn’t just a hyperbolic opinion of the Traken Union. “They say the atmosphere there was so full of goodness that evil just shrivelled up and died.” It’s not a metaphor, either. It’s expressed literally.

The Keeper explains that evil occasionally comes to Traken. When that happens, Traken is so pure that evil is petrified instantly. Of course, the latest arrival is the Master’s TARDIS, but the Keeper makes it sound like evil visits quite regularly and this happens quite frequently. More than that, though, Traken’s environment seems to be explicitly empathic. Speaking of the newest addition, the Keeper notes, “It’s baleful influence will not extend beyond the grove, and even here it will only produce a few weeds.” It’s very difficult to imagine a strictly rational explanation for this that would not sound like techno-babble covering for magic.

Everything in Traken appears to be connected through some sort of nexus. You could argue that the Keeper of Traken is that nexus, but it seems far more metaphysical and spiritual than literal. Indeed, his last days seem almost like a biblical end of days:

I speak for the many peoples of the Traken Union. They ask why crops fail, why droughts and floods disturb our planets. And now, violent death in the very precinct of the court itself. What do we tell them?

Normal events, Consul, when the span of our Keeper nears its end.

The death of the Keeper provokes powerful storms. His decay and weakness is mirrored in the increased corruption of Traken society itself. The Keeper of Traken is arguably something of a fairy tale, and I really like that aspect of it.

Of course, The Keeper of Traken ultimately ends up playing into the themes laid out above by Bidmead. It hits on this idea of the conflict between the rational and the irrational. Traken’s power is apparently routed in the “source manipulator”, but the society has built up so many customs and traditions that the technology has practically become magic. The story uses heavy religious imagery. The officials on Traken are referred to a “proctors” and the planet is governed by “sacred law.”

The Keeper himself is summoned through a ritual that almost seems religious, with the audience kneeling and repeating a mantra. “Keeper of Traken, by unanimous consent, your consul summons you.” The decay of Traken is accelerated when the Master gains control of Kassia by forcing her to wear a priest-like collar. Indeed, he controls all of his subjects through those collars. That said, religion isn’t the only threat to Traken’s well-being.

I always found the scene where Nyssa bribes Proctor Neman to clear a bunch of peaceful protesters to suggest that perhaps political decay was occurring as well. I know we’re meant to consider Nyssa sympathetic, but there are some sinister undertones to her instructions. “They offend the dignity of the Keeper. Have them removed.” Neman responds, “But that is not lawful, lady.” Nyssa instructs him, flashing her purse, “My father and other consuls determine what is lawful.” It sounds almost fascist, as the daughter of a political official bribes law enforcement to break up a peaceful assembly.

Indeed, Johnny Byrne’s script makes it explicit that the decay is more than merely religious or political in nature. It’s social. It’s the kind of thing that reason can’t account for. Finding a dead body, Seron asks, “Well, Tremas? Has science brought us any nearer discovering how the Foster died?” Sadly, there’s no rational way to account for that sort of thing. It’s telling how foreign the very concept of murder seems to the inhabitants of Traken, as Katura responds, “Murder? Here, in the precincts of the court?” It seems like the death of the Keeper is somehow causing a breakdown in society.

Of course, this fits well with the broader themes of the season. This is the end of an era, not just for Traken, but also for the show itself. The decay and death of the Keeper mirrors that of the Doctor. “Listen closely, Doctor,” the Keeper advises. “As you see, the passing ages have taken toll of me.” The Doctor acknowledges, “Yes, yes, I know that feeling.” In a nice touch, the Keeper tries to set the audiences’ minds at ease. “But unlike you, my time of dissolution is near and the power entrusted to me is ebbing away.” Oh, if only he knew!

As with the rest of the season, Baker’s Doctor is subdued here. He’s even unsure whether or not he set a course of Traken. When Adric denies changing the direction of the TARDIS, the Doctor remarks, “But I didn’t. Did I?” In fact, he can’t even recall whether he’s been to Traken or not. “I don’t think I’ve actually been there,” he tells Adric, which is an ambiguous statement. Later on, he elaborates, “You know, I really may have been to Traken. It’s so difficult to keep track of.” While he has had this problem before, it’s generally been treated as comic relief – his experiences are so vast that he can’t remember them all! – rather than seen as evidence that his time is rapidly approaching. He even concedes that his beloved TARDIS has seen better days. “It badly needs an overhaul.”

As such, there’s something wonderfully appropriate about the Doctor’s reaction to the passing of the Keeper. As the consuls prepare to go through with the ritual to name the new Keeper, the Doctor tries desperately to halt the changeover, to stop the transition. “Don’t complete the transition,” he begs, and it seems almost like he’s pleading with the producers of the show, a more subtle variation on the Tenth Doctor’s “I don’t want to go.” Given that the Fourth Doctor is facing a similar transition himself, it’s a nice touch.

Indeed, you could argue that – based on Asylum – since the Fourth Doctor knew that Nyssa would be a companion of the Fifth Doctor, he was desperately trying to avoid his regeneration by leaving her behind. While there are still lots of questions to be answered about the Watcher, at least his decision to bring Nyssa to Logopolis makes sense in that context. The Doctor tried to avoid fate, but you can’t do it like that.

And then, finally, there’s the episode’s resolution, which feels like a nice nod to fans, and a reminder that the death of the Fourth Doctor is not the end. Adric and Nyssa are able to figure out how to save Traken, but it involves destroying one of its fundamental building blocks, its most powerful attribute. “We can destroy Melkur, Nyssa, but only by completely destroying the Source.” It is destruction, but it also life. You remove that aspect, but the rest lives on. The Fourth Doctor may be dying, but Doctor Who lives on.

I really like The Keeper of Traken.Matthew Waterhouse’s performance as Adric (who is much less tolerable now Romana has left) is pretty much the weakest link, which isn’t the worst problem that could face a show like this. It’s easily the most successful of the trilogy of stories that serves to bring Doctor Who from the Fourth Doctor to the Fifth Doctor. It works on its own merits as a great Doctor Who story, but it works even better in context. That’s a very rare attribute, and it’s something that stands strongly to the story’s credit.

Filed under: Television | Tagged: arts, Barry Letts, bbc, christopher h. bidmead, Deadly Assassin, doctor, doctor who, DoctorWho, Fourth Doctor, Gallifrey, Keeper of Traken, Master, Nyssa, science fiction, tardis, Tom Baker, Unearthly Child, William Hartnell |

Excellent review and analysis. Here’s a link to my own write-up:

Cheers!