To celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of Star Trek: The Next Generation, and also next year’s release of Star Trek: Into Darkness, I’m taking a look at the recent blu ray release of the first season, episode-by-episode. Check back daily for the latest review.

I remember that I never really like Where No One Has Gone Before when I was younger. Even now, I have a bit of a tough time counting it among the best episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation. However, despite that, I’ve actually warmed to it quite a bit on this rewatch. It’s not brilliantly constructed as an hour of television, and I wouldn’t even count it as the best produced in this first season of the second Star Trek series. However, it does something that a lot of other episodes in this run try to do, and fail to accomplish.

It manages to evoke the spirit of Star Trek.

I’ve written a bit before about how the first season of Star Trek: The Next Generation gets a bit stuck on the idea of “what Star Trek should be”, spending far too long playing out the tropes from the classic Star Trek show instead of finding its own feet. This was most obvious in The Naked Now, which was pretty much a direct life from an episode of the first season of the original Star Trek. It was the most obvious example, but it was not alone.

The first season is scattered with episodes that play out familiar gimmicks and plot devices as some sort of misjudged homage to the original series. Code of Honour featured an alien species that looked like an ancient Earth culture, The Last Outpost featured a planet left by a dead alien species, and introduced a new enemy that had never been seen by human eyes before. Where No One Has Gone Before continues the trend, to the point where it feels like it could be an episode of classic Star Trek.

An arrogant blowhard arrives on the ship, tinkers with the engines and causes a situation where the crew are confronted with their thoughts made flesh. They only return home with the help of a god-like being masquerading as a humanoid life form. In a way, Where No One Has Gone Before is perhaps the purest distillation of Gene Roddenberry’s vision of Star Trek, and it impresses on that level. It’s a story about the unknown and how we relate to it – and the link between reality and how we perceive it.

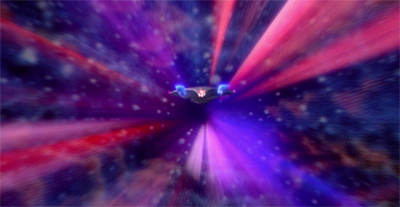

On a more superficial level, it also helps that Where No One Has Gone Before is perhaps the episode that benefits most from the high definition upgrade. The special effects for the Enterprise’s trip into the unknown look remarkably impressive, as if they were only rendered yesterday. Where No One Has Gone Before is proof of just what this project can do, and it teases me with the possibilities for later releases in the line.

That’s not to suggest that Where No One Has Gone Before is perfect or anywhere near it. While it’s conceptually fascinating and embodies the very best of the optimism and curiosity at the heart of the franchise, it’s also a story without a conflict to drive it. There’s no real mystery and no real suspense. Literally all it takes for the crew to get home is to close their eyes and wish really hard. They don’t even have to close their eyes. I think my earlier dismissal of the episode was based on this lack of conflict to define the show, and while I have tempered with age, it’s still a bit of a problem.

It is not nearly as much of a problem as the script’s focus on Wesley Crusher. It is possible for a Star Trek show to feature a kid without being annoying. I know this because I have watched all of Deep Space Nine. I don’t blame Wheaton for Wesley’s issues as a character. Wheaton might be over-excited and too damn chirpy, but it’s the only way to play the character as written. Wesley is written as a kid who is smarter than all the characters around him, despite the fact that they have been trained for the jobs that they are doing, and many of them have decades of life-experience on him.

More than that, the statistical likelihood of Wesley being wrong in any circumstance rapidly approaches zero, so any conflict on the show seems to inevitably resolve with him in the right. This is irritating enough on its own, and Where No One Has Gone Before would feel a bit cheap for how Wesley is the only character to understand the Traveller’s hyper-complex language. (I can understand his childish innocence explaining how he is the only one to notice the Traveller.) The episode compounds the problem by having the Traveller tell Picard (and the audience) how awesome Wesley is. I want to watch Star Trek: The Next Generation, not “The Adventures of Young Mozart in the 24th Century.”

If you can get past that (and it’s a big “if”) there’s a lot of good stuff here. Where No One Has Gone Before effectively concedes that Star Trek doesn’t really run on technobabble, something that Star Trek: Voyager never quite learned. When Riker asks Chief Engineer Argoyle if Kosinski’s plan could damage the Enterprise, Argoyle responds, “How could it? It’s meaningless.” After Kosinski provides some technobabble on the bridge, Riker speaks for the audience. “To tell the truth sir, it sounds like nonsense.”

So, if Star Trek doesn’t run on technobabble, what does it run on? Well, prepare to suspend your cynicism. It runs on innocence and magic. After all, the plot is resolved by the crew wishing, really hard. Kosinski’s technobabble-ladden bull crap is punctuated with conversations between Wesley the Traveller, discussing inherently humanist concepts. While the idea that could push a ship out of the realm of the known universe requires suspension of disbelief, it makes much more sense than a few lines about “coils” and “neutrinos” and “polarity.“

Wesley postulates existentialist philosophy from the Traveller’s calculations. “That space and time and thought aren’t the separate things they appear to be? I just thought the formula you were using said something like that.” The Traveller rebukes him, “Boy, don’t ever say that again. And especially not at your age in a world that’s not ready for such… such dangerous nonsense.” Those are real ideas and concepts, grand ideas in terms that can be understood and digested. The Traveller might dismiss them as “dangerous nonsense”, but it makes more sense than anything Kosinski says.

Even Kosinski is dismissive of the Traveller’s logic, responding, “That’s just so much nonsense. You’re asking us to believe in magic.” Yes, but isn’t that what all Star Trek does? All that Where No One Has Gone Before concedes is that Star Trek is more about magic fantasy than hard science fiction, despite what the behind-the-scenes crew might suggest or argue. There’s a rather wonderful exhange between Picard and the Traveller that sums up the philosophy of Star Trek as a whole:

I am a Traveller.

Traveller? What is your destination?

Destination?

Yes, what place are you trying to reach?

Ah, place. No. There is no specific place I wish to go.

Then what is the purpose of your journey?

Curiosity.

It’s optimistic, humanist curiosity that drives Gene Roddenberry’s version of Star Trek, the belief that the universe is a wondrous and welcoming place full of imagination and beauty. It is Data, the most inhuman (and yet also the most human) of the crew who suggests that the ship should capitalise on its trip into the unknown. “Captain, we’re here. Why not avail ourselves of this opportunity for study? There is a giant protostar here in the process of forming. No other vessel has been out this far.”

The Traveller’s suggestion that humanity is not quite ready for everything out there makes a nice change of pace from the “humans are perfect” message of The Last Outpost. We are pretty great, I’ll concede, but perfection is a journey rather than a destination and Where No One Has Gone Before really gets that aspect of Star Trek – the notion that the quest isn’t just to visit exotic locales and lord it over other species, but to grow and develop in our own way. It is also a much more efficient storytelling technique. Protagonists that have already achieved perfection tend to be rather dull, but there’s something exciting about the idea that there is more to see, more to learn and room to grow.

In a way, Where No One Has Gone Before is about knowledge and belief, and our ability to accept realities that we deem impossible – to transcend our perception of reality. When he is told how far the ship was travelled, Picard’s immediate response is denial. “I can’t accept that.” The Traveller argues that human aren’t ready to travel this far, suggesting that the distance we travel is somehow linked to our ability to understand and comprehend. The further we travel, the more we comprehend, and vice versa. As we travel, concepts like reality become elastic and flexible.

Part of the problem with Kosinski is that he really has no altruistic world view. His advances in technology exist to give him some sense of self-worth, and the episode repeatedly hints that Kosinski is dealing with severe self-esteem issues. When Riker tells Argoyle to let Kosinski try, the scientist vocally complains, “What do you mean, let him try it? Don’t talk about me in the third person like I’m not standing right here!”

As such, Kosinski doesn’t have any grand aspirations for the betterment of mankind. He has no desire to explain himself, or to enter discussions or exchange ideas. He has documented his process, because one imagines Starfleet probably requires some paperwork before they let him tinker with the flagship, but he has no interest in furthering discussion or inquiry. “Surely you’re not saying it’s unexplainable?” Argoyle asks him after Kosinski dismisses the first round of questions.

Kosinski rather bluntly responds to the Chief Engineer’s questions. “I’m saying I’m not a teacher, nor do I wish to become one,” he remarks, dismissively. “I have neither the inclination nor the time.” However, we are all teachers in some fashion, whether we want to be or not. The exchange of ideas (or teaching) is one of the things that constantly pushes humanity forward, and failure to share only hinders progress.

It’s our willingness to accept and to understand that which defines us. The Enterprise is flung to a part of space where the crew’s own fears and insecurities can kill them. If they are cynical, if they believe that the universe is a cold and empty place waiting to kill them, then they will die. However, if their minds are open and their thoughts optimistic, the trip offers limitless potential. Picard seems to come across his own mother, and is afforded a conversation with her, something that seems to give him great peace. At another point, he is almost swallowed by the black void of space.

Kosinski’s inability to evolve his thinking pushes him to the edge of a breakdown. “I honestly thought it was me,” he confesses. “I thought somehow, somehow I was operating on his level.”Kosinski didn’t mean harm, despite his condescending attitude towards the crew. He had just closed his mind and that blinded him to the reality of the situation. There’s something strangely sweet about the relationship between the Traveller and Kosinski, a weird co-dependence that never feels parasitic or exploitative.

It is somewhat heartening that even the Traveller refuses to dismiss Kosinski, hinting at an optimistic humanist philosophy that reflects that of the series on its best days. “Is Mister Kosinski like he sounds? A joke?” Wesley asks after things go wrong. The audience is certainly thinking the same thing, and it would be easy to imagine the Traveller resents Kosinski for stealing the glory. Instead, the Traveller seems almost affectionate in his appraisal of Kosinski, “No, that’s too cruel. He has sensed some small part of it.”

The use of flashbacks and imaginary segues is generally quite decent. I like the idea of discovering Worf has a pet, and there’s something quite charming about the officer playing an imaginary quartet. On the other hand, Yar’s dream about “being chased by a rape gang”feels a little out of place. Yar’s decidedly eighties fashion, the rather obvious presence of a cat and Denise Crosby’s acting serve to make the moment more awkward than emotionally effective. I’m sure that there must have been a way to introduce her back story with a bit more subtlety.

Where No One Has Gone Before isn’t the very best of Star Trek. It’s not even the best of this first season. However, it’s perhaps the only time in this awkward first year where the conscious attempts to emulate the original Star Trek really work. It was loosely based on a novel featuring the original series characters (The Wounded Sky), and it definitely wouldn’t have felt out of place among the show’s three-season run. (Although probably with crappier effects, to be fair.)

It’s very much the essence of Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek, with an optimistic and humanist look at life in the future. This doesn’t necessarily make for the most compelling drama, but it does demonstrate that Star Trek: The Next Generation had lost none of the heart of its predecessor. Of this opening salvo of episodes, it’s Where No One Has Gone Before that holds the most promise and potential for the future.

I might be coloured by the fact that none of the episodes around it are especially brilliant, but I really enjoyed Where No One Has Gone Before on its own terms. It also serves as a great advertisement for the high definition upgrade, probably the best so far.

Read our reviews of the first season of Star Trek: The Next Generation:

- Encounter at Farpoint

- The Naked Now

- Supplemental: Star Trek – The Naked Time

- Code of Honour

- The Last Outpost

- Where No One Has Gone Before

- Supplemental: Star Trek – The Wounded Sky by Diane Duane

- Lonely Among Us

- Justice

- The Battle

- Supplemental: Reunion by Michael Jan Friedman

- Supplemental: (DC Comics, 1989) #59-61 – Children of Chaos/Mother of Madness/Brothers in Darkness

- Hide & Q

- Haven

- The Big Goodbye

- Datalore

- Angel One

- 11001001

- Too Short a Season

- When the Bough Breaks

- Home Soil

- Supplemental: Star Trek – The Devil in the Dark

- Coming of Age

- Heart of Glory

- Arsenal of Freedom

- Symbiosis

- Skin of Evil

- Supplemental: Survivors by Jean Lorrah

- We’ll Always Have Paris

- Conspiracy

- The Neutral Zone

- Supplemental: Operation Assimilation

- Supplemental: The Lost Era – Serpents Among the Ruins by David R. George III

Filed under: The Next Generation | Tagged: best of both worlds, Denise Crosby, gene roddenberry, history, Naked Now, Shopping, star trek, Star Trek Next Generation, Star Trek's Next Generation, star trek: enterprise, star trek: the original series, Traveller, Wesley, Wesley Crusher, Where No One Has Gone Before, William Riker |

Well said.

When this played in theatres last year, the audience erupted into laughter when the guy in the skant showed up. It was satisfying.

I agree with the overall plot of your review: this is the first time TNG felt like Star Trek.

Thanks. I’m in Europe, so we don’t get the theatrical screenings, I’m afraid. It would have been something. Still, I like Where No One Has Gone Before despite its problems. It feels like Star Trek, as you said, rather than trying to emulate the execution (and ignoring the spirit) like so many other first year episodes did.

This is the first indication, after Farpoint, of what the series could be. The actors felt more comfortable, the episode doesn’t feel like just a TOS knoc-off, and while I can’t rightly call it a good episode, it’s also not a bad one. Eric Menyuk delivered a strong performance as the Traveler, making what could’ve been a really annoying character into an oddly effective one. And Kosinski was great. I kinda wanted to see more of him. He was a surprisingly deep character.

I actually felt sorry for Kosinski. The guy had no idea he was being used. Yes, he was a dick, but I felt really sad that he had all this taken away from him, and I like that the show made the Traveller sympathetic to Kosinski, when it would be easier to paint him a talentless jerk.

I also agree that there’s a lot of raw potential here, and it’s the first time we’ve seen that since Farpoint.

I finally started re-watching some of the first season on TNG on Netflix. Sitting down to watch “Where No One Has Gone Before,” I was a startled to realize that I had never actually seen it before. I was even more startled at how much I enjoyed it. I previously didn’t think that there had been any better-than-average episodes of TNG until towards the end of the first season, but obviously I was wrong. This episode is actually one of my favorites from the first year of the show. A large part of that is the excellent direction by Rob Bowman and the evocative music by Ron Jones, both of which heighten the atmosphere of the already-unusual story.

It is a highlight of the first season, especially to this point. It’s the first episode I liked, if I remember correctly.