The wonderful folks at the BBC have given me access to their BBC Global iPlayer for a month to give the service a go and trawl through the archives. Read my thoughts on the service here, but I thought I’d also take the opportunity to enjoy some of the fantastic content.

You might very well think that… I couldn’t possibly comment.

House of Cards is an uncanny political drama. Based on the book written by Michael Dodds, the former “baby faced assassin” for Margaret Thatcher, one wonders just how much of this very dark thriller might actually be based on fact. Charting the rise of the Chief Whip of the Conservative Party, Francis Urquhart, it’s a disturbing exploration of the workings of the system as our villainous protagonist manages to efficiently (and sometimes brutally) remove any obstacles on his path to power. It’s often darkly hilarious, brutally sinister and strangely compelling – sometimes at the same time. While airing, it was granted a sense of relevance by the resignation of then-sitting Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, but it remains a gripping example of British television drama even two decades after it originally aired.

Apparently David Fincher is helming an American adaptation of the show that will star Kevin Spacey in the title role, set in the US Government. It certainly looks fascinating, and is being positioned as the highest profile “Netflix original” television series. While the pedigree is very strong, and I couldn’t imagine two finer names attached to it, part of me wonders if House of Cards could work outside a British context. Of course, politics are just as cynical anywhere in the world. Still there’s a faint notion of class underscoring Francis Urquhart, that inherently contradictory idea of being both a gentleman and a monster at the same time.

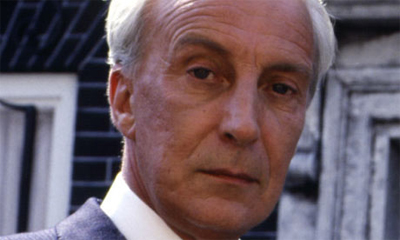

Ian Richardson is Francis Urquhart. I’d go even further and argue that Ian Richardson is House of Cards. The subject matter of the series – the ousting of a sitting Prime Minister and the brutal contest that follows – is absolutely fascinating of itself, but it’s Richardson who holds the whole thing together through a mesmerising lead performance. It’s hard to imagine any other actor being so brutal and sinister, while managing to remain oddly compelling. On a more practical note, it’s very hard to imagine any actor except Richardson making Urquhart’s asides to the camera seem quite natural. It’s quite remarkable that having the lead character literally turn to the camera and start addressing us directly doesn’t take us out of the story at all.

Of course, Richardson is a talented veteran of film and television. Even by the time he had landed this juicy lead role he was a recognisable face. He had appeared as Bill Haydon in the BBC’s adaptation of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and had been popping up in various films and shows by any number of unique British talents, including Brazil by Terry Gilliam. However, Richardson has never been better than he is as Urquhart. With that wry half-smile half-smirk that often accompanies his dry observations, Richardson makes it quite difficult to hate Urquhart, even though we know we should. We know he’s not a nice man from practically the moment we meet him, even if his methods get considerably more sinister as the show reaches its climax.

Urquhart is the Chief Whip of the Conservative Party, the party of government at the time the novel was written and the show was originally aired. His job is essentially to keep the party’s elected officials in line when they’ve been “a bit naughty”, playing “prefect” to a bunch of elder Statesmen. Of course, his job isn’t so much about removing their vices as it is about managing and controlling them. Urquhart is known to compile and store information that might be useful down the line, even if he might fake some half-hearted concern or outrage for indiscretions. On discovering a party organiser’s cocaine addiction, he takes great pleasure in phrasing the question, “I know this sounds old-fashioned, but isn’t it illegal?”

Of course, Urquhart is entirely predatory. “Surprised?” he asks us as he helps distract a drunk who had been hassling the Prime Minister. As he escorts the disgruntled gentleman to the pub, he explains, “Well, everybody can be valuable. That’s my philosophy.” Throughout the series, Urquhart demonstrates a keen eye for human weakness, striking at and exploiting the weak points in his colleagues’ armour. He pimps out a staff worker to create a sex tape of an opponent. He attacks the Prime Minister through his weak-willed and alcoholic brother.

It’s amazing how charming Urquhart seems through this, as he offers false reassurances to the audience. We know, of course, that these are Urquhart’s self-serving justifications. “We did the chap a favour,” he insists of the Prime Minister, “even if he doesn’t know it. He was in the trap and screaming from the moment he took office.” He organised the leadership coup because the Prime Minister passed him over for a Cabinet position, no matter how he might attempt to retroactively justify his actions. Later on, as he scuttles the leadership ambitions of various part members, he states, “they had to be stopped for the good of the country.” During one of his darkest moments, he tries to rationalise even further, “This is an act of mercy. Truly.”

It’s to the credit of both Richardson and director Paul Seed that we’re never entirely sure whether Urquhart is just trying to convince the audience, or to convince himself. His Shakespearean asides to the camera are far more candid than his dialogue with other characters, and far more reflective, but they also skew the truth and try to present Urquhart as a more noble figure than his actions will attest. It’s hard to determine if Urquhart is in some form of denial about what he’s actually doing, trying to make it more palpable to himself, or if he’s simply lying to us to try to keep us at least a little on-side.

What’s fascinating about Urquhart, however, is the contrast between his internal and external lives. We see how he operates, and how brutally manipulative and efficient he might be – how sociopathic his behaviour actually is. It’s interesting to discover that he doesn’t mask these tendencies by being a well-loved member of the circle, but inside by pretending to be the most boring person imaginable. I can’t help but feel that this was Dodds’ most scathing attack on the Conservative party – the insinuation that the naked ambition and sociopathy wasn’t hidden behind a well-loved or socially-acceptable veneer, but was masked by a dull and boring exterior.

Urquhart isn’t hated by his colleagues who are unaware of his actions and motives, but he isn’t loved either. In fact, when he contests the leadership, he’s presented as very much the unengaging, politically boring, “undefined middle ground” candidate. We know little of Urquhart’s politics based on the series, although the Prime Minister does hint that Urquhart leans to the right within the Conservative Party. (Asked to put together a new cabinet, the prime Minister notes “None of the names you mention are from the liberal wing of the party.”)

Urquhart dismisses one of his competitors as “a lout, a lecher, a racist, an anti-semite and a bully”, as if to claim that Urquhart is at least a more moderate and modern person, one beyond such petty flaws and prejudices. While this might be true (well, except for the fact Urquhart is definitely a “bully”), we do see Urquhart exploit such positions for his own gain. He’s not a “lecher”, but he is a pimp and an adulterer – not for any sexual gratification, but as part of his lust for power. He’s not anti-semitic, but he does exploit anti-semitic feelings towards an opponent. He declines to come out as homophobic himself, but he is sure to leak Samuels’ pro-gay-rights stance in order to scupper his bid for leadership.

while Urquhart is undoubtedly the series’ greatest strength, its focus on him is probably its greatest weakness. The other characters exist almost purely as defined by Urquhart, which means they aren’t necessarily developed too much. Urquhart’s wife is an especially interesting example, as she seems to encourage him to seize power using any means necessary, and encourages him to secure a young woman’s loyalty in any way possible. There’s something of Lady MacBeth about her as she tells her husband, “I know that you’re capable of doing what is necessary.”

Still, she seems curiously undefined. She seems to spur her husband on at the start, and stands faithfully by him – but is everything that happens after that initial point just him? What level of trust exists between the pair? Do either of them have any lines they won’t cross or any points that they might disagree on? Does Elizabeth Urquhart merely support her husband in his decisions, or does she encourage them? Does she push him further than he might otherwise go, or does she simply reinforce his own feelings?

More interesting, however, is the curious relationship between Urquhart and reporter Mattie Storrin. A “teenager from the sticks”, Mattie very clearly has some serious daddy issues, and the interplay between Richardson and actress Susannah Harker is superb. There’s a brilliantly unsettling chemistry between the pair, and the script from Andrew Davies leaves us feeling quite a bit disturbed about their interactions.

Despite the excellence of the miniseries, there are still one or two missteps and awkward moments that feel strangely out of place. It feels weird to place so much emphasis on the scene where Mattie discovers who is behind the whole crisis, given that we already know and have known from pretty much the first twenty minutes of the first episode. While the use of Mattie’s tape recordings to create an auditory montage is quite clever, it still feels a little strange that the revelation is treated as such a big moment. I know that Mattie realising it’s Urquhart is a big moment, but the show still structures it as if we’re uncovering the information alongside her.

There’s also a moment featuring a character who is about to die (even if he doesn’t realise it). We know that he’s about to die, even if he doesn’t. However, the script milks the moment for all it’s worth, engaging in paltry sentimentality as the character in question monologues about how he plans to fix his life and his wonderful childhood. It feels just a little overly sentimental and exploitive in a miniseries that has remained rather brilliantly detached from everything unfolding. In fact, it’s that detachment that allows the series to work so well.

The production design on the serial is superb, and it really looks remarkably impressive. After all, the corridors of the British government do tend to look quite fantastic anyway, within the halls of the House of Commons. Jim Parker’s stylish score helps continue that wonderful dichotomy between high class and base conduct that Richardson’s superb central performance captures so very well. Whatever sordid stuff might be unfolding on screen, you can rest assured that it the music gives it a classy air.

House of Cards is a phenomenal television drama, featuring a phenomenal central performance. It’s well worth a look for any political junkies out there.

Filed under: Television | Tagged: bbc, BBC iPlayer, Conservative, Conservative Party, David Cameron, david fincher, Francis Urquhart, House of Cards, house of cards (bbc tv show), house of cards (bbc), house of cards (netflix), Ian Richardson, margaret thatcher, netflix, Parties, politics, Prime Minister, United States |

But what is your take on “who” had the tapes in the end? And better yet, why were they released?

Hi Paula. It’s actually – without spoiling anything – dealt with in the follow-up. To Play the King. Which is highly recommended as almost as good.