We’re currently blogging as part of the “For the Love of Film Noir” blogathon (hosted by Ferdy on Films and The Self-Styled Siren) to raise money to help restore the 1950’s film noir The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me). It’s a good cause which’ll help preserve our rich cinematic heritage for the ages, and you can donate by clicking here. Over the course of the event, running from 14th through 21st February, I’m taking a look at the more modern films that have been inspired or shaped by noir. Today’s theme is “cyber noir” – the unlikely combination of sci-fi and film noir to make an oh-so-tasty film.

Blade Runner is arguably more of a film noir than a science-fiction film. Sure, it features robots and flying cars, but the atmosphere is set by a constant downpour in the streets, while characters wandering around in trenchcoats and questions of identity and moral ambiguity hang heavily in the air. Though the funky Vangelis soundtrack may lead you to believe otherwise, Blade Runner is perhaps one of the most faithful films in the neo-noir film movement. The flying cars are just on top of that.

I remember when I first saw Blade Runner. I was about twelve. It was on on a Sunday night. I had school the following morning, and Mr. Kineally brought it up in our Technical Drawing class. Mr. Kineally had a wonderful style of teaching. he’d draw the shape he wanted us to draw in about thirty seconds at the start of the class, and we’d spend the rest of the class trying to emulate him, while he discussed matters great and trivial with us. If we needed help, he’d give it, or he’d wander around to see if we were struggling.

But he’d also just chat with us about football or film. Blade Runner was the topic of conversation that afternoon, and he wasn’t particularly impressed with it. He’d heard so much, and it had been “just okay”. I agreed with him at the time. It was a little awkward at times and difficult to get into. It was only when I got a chance to jump into Ridley Scott’s Final Cut that I could fully get on board with the film. If you are looking for a particular edition to pick up, I recommend the Final Cut. Anyway, enough anecdote, let’s talk about the film.

Rick Dekkard is a Blade Runner. As the introductory text explains to us, this means he hunts down rogue robots who might have snuck back to Earth. Working in the Los Angeles of 2019 (it seems that, even in the future, Los Angeles is the perfect home for these sorts of adventures), Dekkard is pretty much freelance law enforcement. He’s bitter and withdrawn, clearly carrying around some deeply personal issues (even though he won’t ever be drawn on them).

He’s the kind of character who will only respond to a request from the police department if he’s placed under arrest first. “You wouldn’t have come if I’d just asked you to,” Bryant explains from behind his desk, before outlining the job he has in mind for Dekkard. Dekkard is reluctant to take the job, even when asked nicely. He has to be strong-armed into it by the authorities. “If you’re not a cop, you’re little people,” Bryant warns him, as it’s made clear that Dekkard has “no choice” in the matter. He’s just a puppet, a cog in a giant machine.

It’s hard not to see the future of any number of private detective characters in Dekkard. He’s good at his job – following clever leads drawn from all manner of sources – but he’s clearly a deeply unhappy person. He drinks like a fish and he’s grumpy as hell. He’s haunted by something. The movie implies that his job is what troubles him, though he won’t admit it – shakes are “part of the business”, he explains at one point. Tasked with hunting down stray replicants, Dekkard is tasked with effectively putting down what look like people. “Have you ever retired a human by mistake?” Rachael asks him at one point, and he denies it. But he kills creatures that (for most intents and purposes) look and act human. That sort of thing must take its toll on a man.

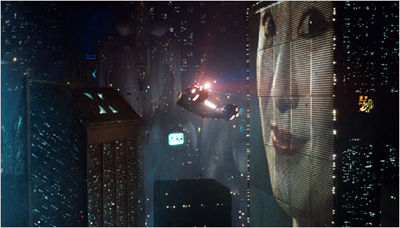

The visual design of Blade Runner is amazing. Even if you’ve never seen the film itself, you’ve likely seen the production design filtered back through countless other sci-fi noir. Blade Runner is pretty much the standard against which dystopian futures are judged, so perfectly crafted is the bleak future. The film famously incorporated large amounts of Asian design into its sets, but what is striking is ho heavily it borrows from the old crime films. There’s alway steam or smog in the air as the rain beats down on the citizens, and almost everything (save the neon) is a dull shade of grey.

Even Vangelis‘ soundtrack, as electronic as it may be at times, is infused with a fair amount of wailing saxophones, like all those classic films. Seriously, remove the synth from the background of the famous Blade Runner Love Theme and you could pretty much set that score against any classic romantic scene to great effect.

Floating balloons broadcast advertisements to the masses, making promises about “off-world colonies”, where citizens may be granted “the chance to begin again in a golden land of opportunity and adventure.” It calls to mind the classic Western genre, and perhaps underscores the philosophical thread which links the Western to the noir and to science fiction. At one time, not too long ago, California was “the golden land of opportunity and adventure” to so many – but it was really just a harsh landscape that broke so many good men.

I’ve always suggested that film noir has a strong link with those sorts of classic cynical Westerns, which explore how futile it is for men to fight against the future (often portrayed as “the railroad”, or civilisation spreading West). I think that the characters in Once Upon a Time in the West could have an interesting conversation with Jake Gittes from Chinatown about how futile it can seem to fight the system. The world, in both Westerns and film noir, is a rough place which will crush you if you try to stand against it. The links between science fiction and the Western are obvious, as they both deal with man’s attempts to control various frontiers (the former often metaphorical or allegorical, while the latter is more literal).

However, as much as Ridley Scott’s style draws from those classic films, the movie’s themes also draw from the grim nihilism and fatalism which underpin a lot of classic noir stories. It’s science fiction, of course, with its big ideas – wonderfully summed up by the title of the work upon which this is based, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – but it approaches them with a cynicism that clearly comes from those darker tales of the thirties and forties.

The world we are presented with is just as artificial as the replicants that Dekkard is tasked to hunt down. We don’t see a single tree over the course of the entire film (save in the lead character’s dreams and photographs), nor a single living animal. The owl in Tyrell’s office is a fake. When Dekkard asks if an exotic dancer’s snake is real, she laughs at him. “Of course it’s not a real snake,” the dancer protests. In a world this clearly artificial, who is to dictate what is real?

It’s interesting that the movie uses animal cruelty as a barometer in the tests to distinguish between human and replicant. There are questions about a tortoise on its back or a butterfly collection (and a killing jar). It’s clear that the suffering of these animals is intended to draw some human sense of compassion, but it’s clearly hypocritical and illogical. The replicants are hunted and chased (and executed) like stray dogs, despite clearly having the capacity to reason and (in at least some cases) feel. Of course, our own principles are somewhat irrational – Rachael would take her son to a doctor for using a killing jar on a butterfly, but would think nothing of swatting a wasp.

“Painful to live in fear, isn’t it?” Leo goads Dekkard at one point, after watching his colleague chasing and executed without so much as a second thought. The replicants can feel fear, they can suffer. “That’s what it is to be a slave,” Batty explains, in the first and only time that the movie uses the word “slave” to describe the relationship between the humans and the replicants. Although we give them names like “loader” and “combat droid”, aren’t they all really slaves? Especially if they can feel and reason?

The replicants only want what we all want – they want more life. They want the chance to live (and, perhaps, to live free of persecution). However, it seems that Batty himself cannot escape his own nature – he’s shown as a violent creature, which makes sense given he was created as a soldier. They are motivated by the same fears that drive us, fears of mortality.

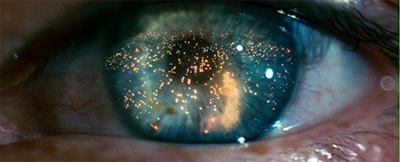

Those fears are heightened because of the prejudice they suffer and their shorter life spans, but Batty manages to sum up a pretty universal fear of death as he observes that “all those moments will be lost… in time… like tears, in the rain.” Of a female replicant, the mysterious Gaff declares, “It’s too bad she won’t live…” However, on reflection, he adds, “but, then again, who does?” The Tyrell slogan is “more human than human”, and perhaps it’s apt. After all, we’re driven by our own fear of mortality, so in order to be “more human”, perhaps these creatures need to be more driven.

Identity is at the heart of the film, to the point that the very nature of Dekkard himself is frequently discussed and debated by fans. When Dekkard discovers that one of Tyrell’s staff is a replicant, but unaware, he asks, “How can it not know what it is?” In all honesty, though – how frank are we with ourselves when it comes to matters like this? How candid can we be with ourselves? Tyrell has found that he can create a better simulation of humanity by embedding memories taken from a live host into these replicant bodies, creating a question of identity. If we are the product of our experiences, then who is this new person? Although the flesh is cybernetic, aren’t they at least as human as the source of the memories? As the replicant explains, she can’t tell what part of her life is her own, or as a result of the memory implants.

The film is really worth picking up on blu ray, by the by. It looks absolutely stunning restored the way that it is, and all four versions of the film are available for your viewing pleasure (plus the workprint). I can’t think of a film that has been better served by DVD and blu ray releases, it really sets a high watermark for the Warner Brothers home video section.

Blade Runner is a film with big ideas. There are some wonderful proposals just sitting out there, regarding the nature of humanity and identity. These core themes work remarkably well against the noir inspired background that director Ridley Scott has created. It’s a huge sign of how fantastic a director Scott is that I can’t unequivocably label this his finest film, but it’s perhaps his most thought-provoking. It’s a film that rewards close attention and repeat viewing.

If you enjoyed this post, please make a donation to the blogathon if you can. All funds go to help restore the classic The Sound of Fury, a very worthwhile cause and a wonderful contribution to make to the arts. Click the image below to donate.

Filed under: Non-Review Reviews | Tagged: blade runner, California, Counties, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Film noir, films, For the Love of Film Noir, For the Love of Film Noir blogathon, For the Love of Film Noir: The Film Preservation Blogathon, hollywood, LA Noire, los angeles, Movies, non-review review, review, rick dekkard, ridley scott, roy batty, science fiction, United States, Vangelis |

Bore Runner. sorry Darren, it just leaves me cold. maybe need to give it another go. nice story about your teacher. we had a maths teacher who actually let us watch Blade Runner once, that and Police Squad episodes.

Hey, you changed your icon! I don’t know, I think Blade Runner is more a movie you feel than anything else. If you are going to try it again, I recommend The Final Cut. No narration and no silly stuntman in a wig smashing through sugar glass windowpanes.

Robert believes that “Ross McG” is British because of the use of the term “maths”. Robert is old enough to remember watching “Police Academy” movies at the cinema / movie theatre.

I suspect Ross is Irish, much like myself.

I’m going to have to review this one for the occasion as well. Realistically, I look for any excuse to watch classic Ridley Scott.

Yep. Ridley Scott sci-fi. It just works.

love love love Blade Runner. Everything about it is so fabulous. But the art direction/costumes/makeup/hair really solidifies its brilliance.

Yep. I think everyone is familiar with the look of the film, even if they don’t even know it exists.

This is one of those movies I have never seen, but I remember the posters and the stills. Your comment “The replicants only want what we all want – they want more life. They want the chance to live (and, perhaps, to live free of persecution)” was interesting to see in light of a recent book I read about a Louisiana slave revolt. Thanks for an interesting essay.

Thanks Joe. Give it a go. You might like it.

http://www.undy-a-hundy.com/?p=1574

Good review, I’d probably argue the Final Cut is far stronger than the original – but great write-up.

Ok, so late last night I caught wind of there being talks about the creation of a new movie in the Blade Runner universe. I also learned that so far, Ridley Scott is not involved?! How can you even talk about making a Blade Runner without Scott at the helm?

Read More: http://www.shawnmichaeladamsonline.com/2011/03/blade-runner-prequel-talks-where-is.html

Philip K. Dick’s novel ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?’ was perfect foundation for Scott’s vision in ‘Blade Runner’, for sure. I read the novel before seeing the film (some 25 yrs ago) and I was pleased with the way of matching the mood and the whole world set in Dick’s novel – depressed individuals, dehumanized society, endless rains…

‘Blade Runner’ is perfect blend of film noir and dystopian sci-fi story spiced with some philosophical issues; its set design is unforgettable, as well as Vangelis’ music score. Overall, it’s a corner stone of sci-fi film, an ornament to dystopian sub-culture…

Yep, one of the truly great modern noir and science-fiction films.

Scott’s grim vision of the future where traditional western ideals of opportunity and shared responsibility have been pushed aside by neo-feudalism (private splendor, public squalor) is what makes me think its probably the most accurate ‘futuristic’ film ever made. The fact that the replicants are the only ones in the story who haven’t had love, compassion and wonder squeezed out of them by their oppressive world is the bitterest of ironies.

A game-changer of a movie and Scott’s best to date.

Agreed, entirely Chris – I always thought that Scott was able to capture the tragedy of the robots perfectly, and I love the pseudo-religious angle that creeps into any movie focusing on the relationship between man and robot, because man is inevitably the most flawed of creators.